- Joined

- Jul 25, 2008

- Messages

- 15,307

- Points

- 113

How will Singapore cope as the vice of US-China rivalry tightens?

Beyond repeating the point that we don’t want to be forced to choose, there are steps – external and internal – that Singapore can take to ease the pressure from the two superpowers.

Joseph Chinyong Liow

Much of the posturing by the US and China is driven as much by domestic political interests as they are by anything else. PHOTO: REUTERS

OCT 13, 2023

The bilateral relationship between the two largest economies in the world is not in a good place, and has not been so for many years now.

If anything, the situation remains brittle, and further deterioration can be easily triggered by another “balloon incident”, another round of tariffs and sanctions, an incident at sea, or a visit involving Taiwan. For us in South-east Asia, the proverbial question of “choice” hangs like the Sword of Damocles over our region.

We have come a long way from Jan 13, 2009, when the former national security adviser in the Carter administration, Mr Zbigniew Brzezinski, proposed that the United States and China should work together to tackle a laundry list of problems afflicting the world. His proposal quickly morphed into the idea of a G-2.

Fast-forward to the present. We know that the G-2 failed to materialise in any substantive way. What set off this tailspin?

Power transition

The Power Transition Theory is probably the most popular in terms of efforts to explain what is going on in US-China relations today.Basically, this theory proposes that when an ascendant state rises to the point of equivalence of power to the dominant state in the international system, and is dissatisfied with the status quo, the likelihood of war is very high because the rising power will want to challenge and displace the incumbent, and the incumbent will not want to cede dominance.

It is clear in today’s context who is the ascendant power, and who is the incumbent power.

Tensions are further heightened by what is called the Security Dilemma. Measures taken by a state to increase its own security tend to heighten the sense of insecurity of other states, leading them to take their own measures to feel more secure, which in turn heightens the insecurities of the first state.

Needless to say, the dynamic also plays out in the Asia-Pacific, where China’s assertiveness has made smaller regional states less secure, resulting in their efforts to strengthen ties with the US. This has in turn made China feel less secure as Beijing accuses the US of trying to contain it. We also see something of this dynamic in the Taiwan Strait.

And today, interactions between the two great powers have also taken on a decidedly ideological flavour, with President Joe Biden casting US-China rivalry as democracy versus autocracy.

Domestic politics

Much of the posturing by the US and China is driven as much by domestic political interests as it is by anything else. That American society is deeply polarised along political lines today is obvious to all. There is, however, one exception – China policy, where both parties are in lockstep on the need to take a hard line. Yet, at the same time, both are also tripping over each other to demonstrate how hawkish they can be while criticising the other party for being weak on China. We can expect this to ramp up as elections loom.As for China, the fact that America persistently calls it out over Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong and, most provocative of all in Beijing’s view, Taiwan, projects US-China rivalry onto Chinese domestic politics. The downturn in US-China relations feeds into a very nationalistic narrative that casts the United States as being dead-set on preventing the Chinese Dream from becoming reality.

Something also needs to be said about the role of leaders. We have to ask how much of a role did Donald Trump, the iconoclastic former president of the US, or Mr Xi Jinping, the most titled leader in the history of modern China, play in escalating strategic competition?

As a princeling, Mr Xi considers himself the legitimate heir of the Communist Party of China’s “mandate of heaven” established by Mao Zedong. As an ideologue, he seems very convinced that he knows what is best for his party and his country. Therein lies the foundation of that singular focus that has driven him to reshape China today as a strong and decisive leader leading in challenging times.

Options for Singapore

So, where does all this leave Singapore, as a small country caught up in the waves of great power rivalry?While Singapore would much prefer not to be placed in a position where it has to choose sides, and it would indeed be wise to avoid being entangled in the US-China rivalry, the harsh reality is that, unless the geopolitical climate changes, we will increasingly find ourselves squeezed.

So, how do we prepare for this growing pressure?

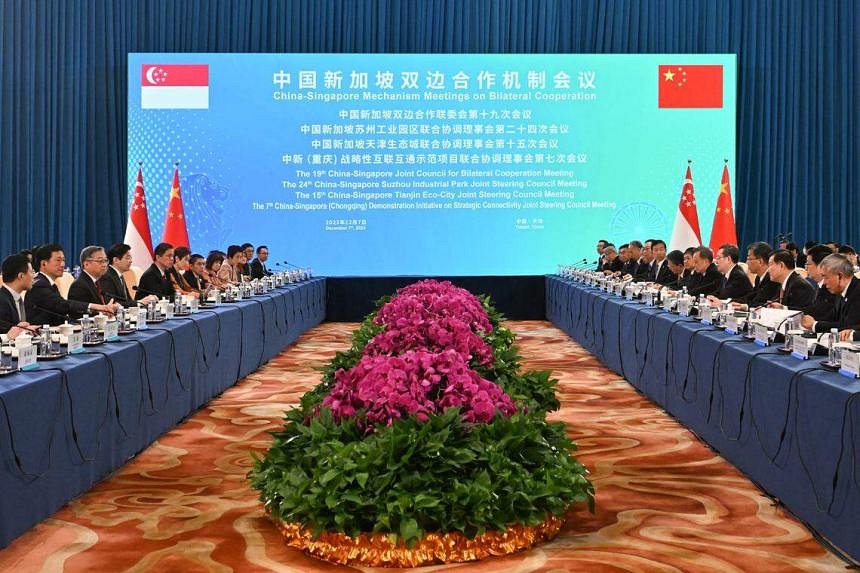

First, both the US and China are important to Singapore, so we have to maintain good relations with both, and avoid casting US-China competition in binary terms. In fact, we should turn the issue on its head: Perhaps what we should also be asking is how do we make them choose us?

The answer to that question lies in our value proposition to them. As a small country whose relevance to the international community is not at all self-evident, and that is heavily dependent on economic linkages with the rest of the world, not least the major economies of the US and China, it behoves us to make ourselves relevant to their strategic, economic and commercial interests, so that neither would want to make us choose.

How do we do that? This leads to my second point. In order to figure out our value proposition for them, we need to understand them better, to understand what makes them tick.

American and Chinese society, politics and decision-making have undergone profound changes in recent years. Once an ardent advocate of economic liberalism and free markets, the US has now embarked on industrial policy. China, too, today looks very different compared with the one that so captivated the world when it hosted the Olympics in 2008.

Better understanding them means more than just understanding how policies are made in Washington DC or Beijing. It is in the nature of being a big power that they don’t put in too much effort and attention learning about small countries, but as a small country, we cannot afford that luxury. We have no choice but to invest time, effort and resources to better understand the big powers around us.

We also need to understand that even if great powers might genuinely not want to foist a choice on small states, make no mistake, they pay close attention to the choices made, and right or wrong, they will draw conclusions from them.

In recent years, American friends (as well as friends from countries from the region that are allies of the US) would frequently ask why Singapore was gravitating towards China. At the same time, Chinese friends would ask why Singapore is so emphatic in our support for a US presence in the region. It is precisely because Singapore has developed a strong international reputation for punching above our weight that how we manage our relations with the US and China in this present climate of growing geopolitical rivalry is of great interest to the rest of the world, not least, to the US and China themselves.

Singapore can of course boldly proclaim that what we will choose is not sides but what’s in our national interest, but the situation has become very complex.

Take Singapore’s position on the Russian invasion of Ukraine, for example. The Singapore Government has made its position very clear, and has gone to great lengths to explain it. Yet there are still a considerable number of Singaporeans who persist in – in fact, insist on – viewing Singapore’s position on the Ukraine war through US-China lenses, even though our opposition to the invasion has nothing to do with our relationship with Washington or Beijing.

Another example is how some citizens understand and process narratives emanating from some external powers that are designed to appeal to diasporic communities. Herein lies a curious but disconcerting twist that is manifested in two ways. First, it speaks to the sophisticated ways in which some external powers may foist choice without obviously saying or doing so, through the narratives they propagate. And second, it poses the disturbing question of whether it is external powers that are forcing us to “choose sides” as it were, or our own population.

This means that our leaders and policymakers will need to explain, educate, explain, educate, and then explain some more, why our foreign policy imperatives and priorities are what they are.

Finally, rather than obsess reactively over choice, we should be forward leaning and proactive to stay ahead of the geopolitical curve.

A forward-leaning diplomatic posture must also involve reinforcing old partnerships and seeking out new ones with other regional powers and with neighbours in Asean, who themselves are trying to avoid becoming entangled in the US-China rivalry. This creates maximum room for autonomy and manoeuvre, which is vital for small states. Indeed, as powerful as the US and China are, they are not the only two countries that count.

There should be no question that the US and China are locked in intense strategic competition that grows sharper by the day.

At the risk of simplifying very complex dynamics, perhaps the definitive questions for the great powers themselves, at the end of the day, are really these. For the US, is it prepared to accept that China is a global power, and to accommodate it? And for China, is it prepared to acknowledge the US is and will remain a major player with deep and legitimate interests in the Asia-Pacific region, and to accept it? In that respect, both are likely prepared to coexist, but at this point, the problem seems to be that both want to do it on terms that are advantageous to them.

All this is to say that while bilateral relations between the two great powers are not in a good place at present, further deterioration can be tempered, and competition managed, if both parties are prepared to turn away from zero-sum calculations.

And by way of a final observation, let me say this. It is not easy to find many countries that have the scope and depth of relations with both the US and China that Singapore has. So, in that sense, we are in a somewhat unique position. And because of this, while we must certainly be realistic about what we think we can do vis-a-vis the two great powers, I also believe that we can do more than we think.

- Joseph Chinyong Liow is Tan Kah Kee chair in comparative and international politics and dean of the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences at Nanyang Technological University. These are edited excerpts from the first IPS-Nathan Lecture he delivered on Tuesday.