South-east Asia could pay dearly for worsening US-China ties

The dangerous deterioration of US-China ties has grave and far-reaching implications, including for Asean states. Regional leaders should make clear their concerns to the two great power rivals.

Chan Heng Chee

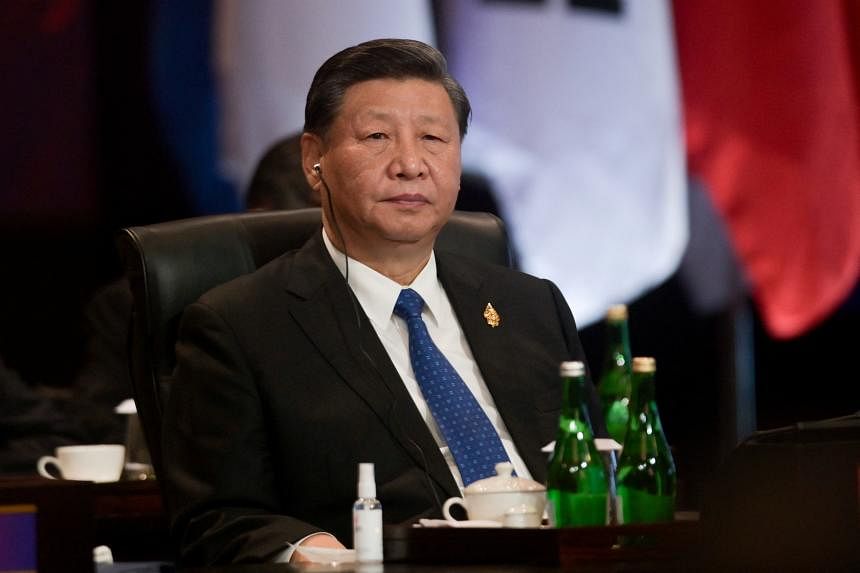

There is an absence of strategic trust between the US and China, and each is ascribing the worst intentions to the other side. PHOTO: REUTERS

NOV 12, 2022

The downward spiralling US-China relationship seems headed for the bottomless pit.

The strategic competition between the United States and China worsened sharply after Russia invaded Ukraine. It has often been asked if Ukraine has affected the way China thinks about Taiwan and reunification. It probably has on many levels, though China was never going to be affected by Russia’s plans. China has its own timetable.

But Ukraine has also affected the way the US and its European allies think about Taiwan. Now, the Western alliance looks at Taiwan through the lens of Ukraine and casts China as Russia. Thus, its members seek to strengthen the deterrence and response for Taiwan accordingly. Taiwan has become entangled in a test of America’s ability, with the help of its allies, to maintain the American-led international order in East Asia. The temperature in the Taiwan Strait has gone up considerably.

Following

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s speech at the 20th Party Congress, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in an interview that China was determined to pursue reunification on a much faster timeline. US Chief of Naval Operations Mike Gilday publicly talked of the possibility of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan before 2024. Admiral Phil Davidson, when he was commander of the US’ Indo-Pacific fleet, told Congress in 2021 that the Chinese military could take action before 2027. American China expert Bonnie Glaser said “the 2027 timeline is baked into US military thinking... but it seems to be based on an assessment of when China would have the capability to invade Taiwan rather than intelligence that provided information on Beijing’s intent”.

China, on its part, questions the “one China” commitment of the United States following the contradictory stances of different parts of the US government. There is an absence of strategic trust between the US and China, and each is ascribing the worst intentions to the other side. Each side is gearing up for conflict.

Tech war’s escalation

The strategic competition has now carried into the technology sphere, which would have far-reaching effects on the economies of China, the United States as well as other countries since we live in an interconnected and globalised world. The Biden administration’s

Chips and Science Act, passed in August, together with National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan’s speech to the Global Emerging Technologies Summit on Sept 16, was in effect a declaration of a technology war on China.

On Oct 6, days before the Communist Party’s 20th congress, the US Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security

placed restrictions on China’s ability to obtain advanced computing chips, develop and maintain supercomputers and manufacture advanced semiconductors.

The latest move bars the export of advanced chips to China made anywhere in the world with US technology and also blocks the export of tools used to make them. Further, there is a ban on US citizens and legal residents working with China’s chip companies. Taken together, the measures are breathtaking. American technology experts say they are the broadest controls issued in a decade. Decoupling will inevitably ensue if it is not already a fait accompli.

America’s moves to protect its technology are not new. In the Obama administration, US officials had already noticed Chinese companies buying up small US technology firms to acquire their know-how.

President Barack Obama did not allow Intel or Nvidia to sell certain types of chips to China with military, supercomputer or security applications. The Trump administration recognised that technology was the major battleground for the US and China, and they needed to protect national security and competitive economic interests. But the Trump administration’s approach was less coordinated and less comprehensive, and it targeted specific Chinese entities.

In fact, Chinese companies were getting access to US technologies as World Trade Organisation rules negotiated during China’s accession allowed it to limit market access to US companies unless they entered into joint ventures with Chinese firms. The sore point for the US was that China should be giving up these developing country advantages now that it was a more developed country, but it had steadfastly refused.

Some commentators have said China should expect this American response because it started the decoupling buzz with Premier Li Keqiang’s announcement of the Made in China 2025 policy in 2015.

But what China was trying to do with MIC 25 was industrial upgrading, moving its economy from heavily featuring textiles and light simple manufacturing to more higher value-added industries. The Chinese were following the playbook of Japan and South Korea and inspired by Germany’s Industry 4.0 plan. But China did make it clear that it wanted to be less dependent on foreign technology and eventually reach 70 per cent self-sufficiency in technology production. China also expressed its ambition to be the leader in artificial intelligence. Whether it thought it could be self-sufficient in deep tech or how soon was another matter.

The US and Europe reacted in unison sharply and negatively. The strong pushback caused China from 2019 to quietly drop mentioning Made in China 2025. Given the Trump administration’s rapid moves to restrict sensitive US technology exports to China and punitive tariffs on Chinese exports to the US, China under President Xi too started to decouple China on its own terms.

Impact on South-east Asia

Watching all this on the sidelines, countries in South-east Asia have concerns. This competition between the two superpowers impacts us gravely, affecting the peace and security of our region and our livelihoods. All of the countries in South-east Asia have a “one China” policy, and we hope the issue of Taiwan can be settled by peaceful means.

What does the US Chips Act, outbound investment screening and technology export curbs mean for Asean? The answer could be – quite a lot.

First, the world economy has become increasingly interdependent for a long time. In recent years, it has accelerated because of improved trade, mobility of capital and labour and new technology. Globalisation and international cooperation have led some developing countries to join the ranks of industrial and industrialising countries, brought medical and scientific discoveries to control diseases, saved lives and tried to keep planet Earth liveable, though this is increasingly hard.

Globalisation does not prevent wars, but in the absence of globalisation, as Financial Times commentator Martin Wolf intones, the fracturing of economic ties will deepen global discord. Even if the latest US moves on technology curbs to China may not mean comprehensive decoupling, they send a powerful signal in that direction.

Second, the Asean economy is quite integrated with China even though the US has the largest cumulative investments in the region. China is Asean’s largest trading partner. According to the Asean Secretariat, the total value of trade in goods between China and Asean in 2020 reached US$516.9 billion (S$725 billion), accounting for a quarter of Asean’s total foreign trade.

Asean is China’s largest trading partner, accounting for 14.7 per cent of China’s trade in 2020. Vietnam’s trade with China is 28.1 per cent of the Asean-China trade, Malaysia’s is 19.2 per cent, Thailand’s 14.4 per cent and Singapore’s 13 per cent. The four Asean countries account for 74.7 per cent of the total China-Asean trade. About half of the trade is in electronic goods. Asean economies will be collateral damage with the technology decoupling and there will be unintended consequences. We are affected but we do not have a vote in the US Congress or a say in US legislation. It is hard to make ourselves heard on matters of national security. It is difficult right now to calculate the outcome.

Some analysts suggest that US-China tensions could result in South-east Asia becoming the beneficiary. But for how long, and how to account for the entire production process, and who owns the diverted supply chains?

Industry leaders in the US all acknowledge there are national security concerns and have indicated they will support and work with the US government, though they note that the instrument used to protect national security should not be blunt.

Clearly, the latest moves will hurt the US semiconductor industry, which derives 30 per cent of its revenues from sales to China. It makes a difference to profit margins that support research and development in the industry. Chubb chief executive Evan Greenberg said at the recent gala dinner of the National Committee on US-China Relations in late October that the US government should challenge China on predatory practices, but that Chinese private sector firms that are not “national security sensitive should be embraced”. He added: “Active American participation in China is on balance good for America. Broad notions of decoupling and self-sufficiency are unrealistic.”

Now we know that presidents Biden and Xi will meet in Bali. That is good news. Leaders should talk, and in person. I also believe that if the region does not speak up, we would have missed an opportunity to impress on the two great powers our deep concerns. We look forward to a more stable and workable outcome and to build peace, security and an economically robust region together.

- Chan Heng Chee is Singapore’s Ambassador-at-Large and a professor at the Lee Kuan Yew Centre for Innovative Cities, Singapore University of Technology and Design.