What is good news and how do we communicated it? (Isaiah 40:1–11)

What is good news and how do we communicate it?

David C. Cramer

Isaiah 40:1–11 is addressed to a people—indeed, to a nation—that is slowly emerging from a prolonged, painful experience of collective trauma.

Old Testament scholars observe that verses 1–11 serve as the prologue to the second major unit of Isaiah, chapters 40–55. The first unit of Isaiah, chapters 1–39, speaks words of judgment on Judah for its sin, idolatry, and oppression. This section leads up to the ultimate judgment on the people in 587 BCE, when Jerusalem is conquered and destroyed by the Babylonian Empire, and many of its people are taken into exile.

In contrast, the second unit of Isaiah is written to the people of Judah as they are returning from exile. As Old Testament scholar Michael Chan

observes, “The exile is anticipated in Chapter 39 and then only assumed in Isaiah 40. It’s as if the editors didn’t need to—or perhaps couldn’t bear to—talk about ‘that’ time, when God handed over God’s beloved Daughter Zion into the hands of a vicious foreign army.”

Chan thus describes how the author is “forced to preach to an audience that had experienced trauma and whose relationship to God had been deeply wounded as a result. For this audience, God’s hiddenness was far more real than God’s presence.”

As with post-exilic Judah, we too are in a moment of (hopefully) emerging—however slowly it may be—from a period of collective trauma. Between a pandemic that has taken hundreds of thousands of lives in the United States alone and has caused untold suffering around the world

and the magnitude of racial and sexualized violence that many of us are just beginning to comprehend, we are a traumatized people.

Yet this text is addressed not to the people themselves but to the messenger or messengers to the people. It’s addressed, quite literally, to those charged with bringing the news to the people. To the herald who brings the press.

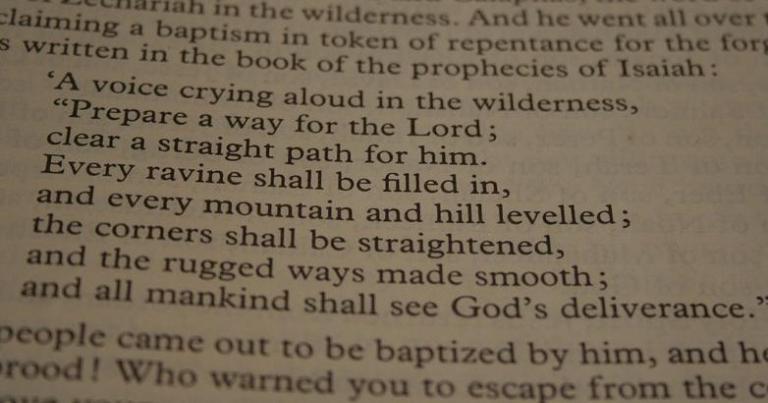

This passage, in other words, is all about words—about communication. Old Testament scholar John Goldingay

writes, “The importance of the notion of communication in vv. 1–11 is indicated by the frequent use of words for communication, ‘say’ (four times), ‘speak’ (twice), ‘call out’ (four times), ‘raise [the voice]’ (twice). The passage is substantially

about words.”

The question, then, is this:

What’s the good news I have to communicate? In addition to this question are two related questions:

For whom is the news I have to communicate good? And how can I communicate this news in a way that it is heard as good?

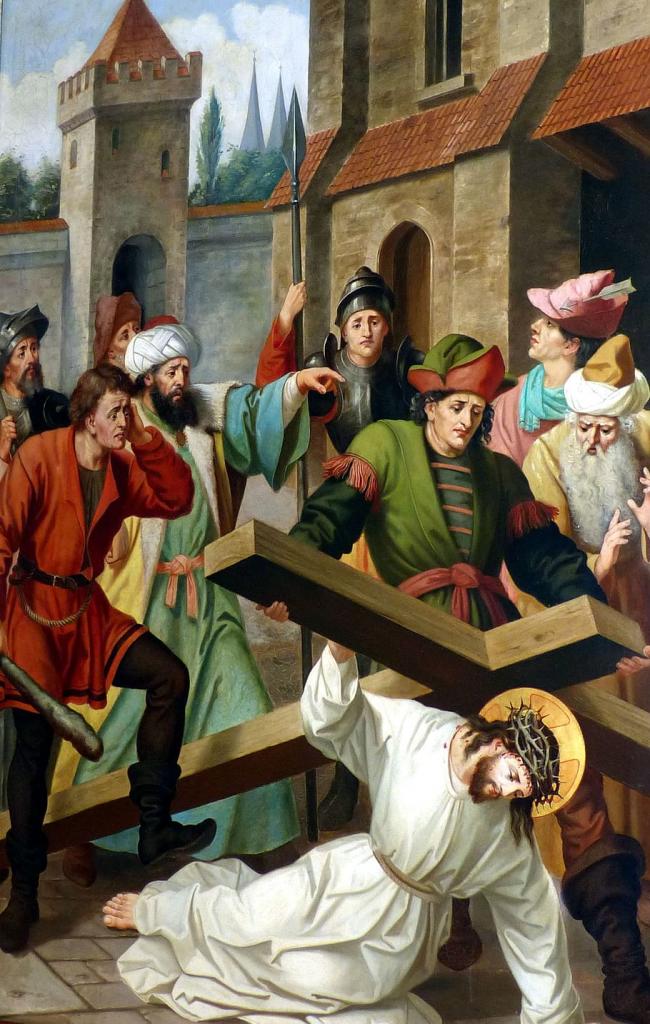

Max Pixel / Creative Commons

What’s the good news I have to communicate?

Having grown up in an evangelical context and come into the Anabaptist fold in my early 20s, I spent a fair amount of time wrestling with the age-old question:

What is the gospel? Is it the

spiritualized message that I learned in my evangelical childhood and youth? Or is it the

social message that I was encountering in my reading of Anabaptist historians and Bible scholars? Or is it perhaps the

political message I was encountering among the more radical Anabaptist theologians and activists?

These questions led me to write my theology dissertation on the influence of the early twentieth-century social gospel theologian Walter Rauschenbusch on contemporary Anabaptist theology and ethics.

But now that I’m in pastoral ministry, I’ve become weary any kind of essentialized definition of the gospel. The gospel, or Greek

euangelion, just means

good news. And good news just is news that is good.

For those returning from exile in Babylon, the good news was a simple but profound message of

comfort. Their sins have been paid for. They will again see the glory of the Lord. The Lord will protect them and gently shepherd them. According to

Ivan Friesen, this “prologue announcing good tidings” presents “a theology of hope resting on a foundation of the Lord’s power and presence.”

For Jewish peasants in first century Palestine, the good news was the arrival of their long-awaited messiah, who would reveal the salvation, deliverance, or liberation of God.

For many who heard Walter Rauschenbusch preach, the good news was that the Kingdom of God is advancing on earth as it is in heaven.

For many who heard Billy Graham preach, the good news was that they could be at peace with God.

As author

Osheta Moore has poignantly shared, the good news for many of our sisters and brothers of color today is that Black lives matter.

In hindsight, it’s kind of silly to do so much hand wringing over the definition of good news. We know it when we hear it! And just because a message of good news isn’t

the comprehensive message of good news for all times and all places doesn’t make it any less good or any less news.

For whom is the news I have to communicate good?

As an editor at Baker Academic and Brazos Press and now at the

Institute of Mennonite Studies, I have had the pleasure of reviewing many a book proposal. And there’s one question on every book proposal that provides a dead giveaway about how realistic the author is about their project:

Who do you envision as the intended audience for your book?

You would be surprised how many authors write something to this effect:

Although this project is written with other scholars in mind, it could be used in an undergrad or seminary classroom or read by pastors or your average person in the pew.

What that kind of answer indicates immediately is that the author has no idea who their message is for, which means there’s a good chance it’s not for anyone. As it turns out, the average person in the pew doesn’t find academic Mennonite theology that interesting, nor do academic Mennonite theologians find books written for the average person in the pew.

As much as we like to believe that our good news should be good news for

everyone, more often than not there’s a specific audience who needs to hear it.

For the prologue to the second part of Isaiah, the good news was for the people of Zion, Jerusalem, and the towns of Judah. Kristin Wendland

observes of this passage:

At the end of this passage the city of Jerusalem, also identified as Zion, is personified. This is a common trope in Isaiah 40-66. . . . However, the place in the Old Testament in which Zion is personified most consistently is in the first two chapters of the book of Lamentations. In Lamentations 1-2 Daughter Zion cries out against the destruction wrought her. She speaks words of accusation against her human enemies and even God. The refrain that comes again and again is, “There is no one to comfort her” . . . At the end of her speeches—and even the end of the book of Lamentations—Daughter Zion receives no response to her cry.

The response to Zion’s laments comes, rather, in other biblical books. The response comes in verses such as Isaiah 40:1 “Comfort, O comfort my people.” The response comes in verses such as Isaiah 40:9 in which the words for Jerusalem to speak are not those of lament but of good news. She is no longer told to wail but to raise her voice without fear. The message given is confident and hopeful, “Here is your God!” Here is a God who comes to feed the flock, to gather the lambs, to lead the mother sheep—to bring comfort. Here is God in whom one may have hope.

We’re all familiar with Jesus’s inaugural sermon in Luke 4:18–19, where he reads from this same scroll of Isaiah to proclaim:

The Spirit of the Lord is on me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners

and recovery of sight for the blind,

to set the oppressed free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.

This is a message of good news with a concrete and specific audience. And, while it was received by its intended audience as good news, there were many others for whom it was heard as a threat to their way of life. While ultimately the liberation of the oppressed is good for both the oppressed and the oppressor, it is more likely to be heard as good by the former than the latter.

How can I communicate this news in a way that it is heard as good?

This prologue in Isaiah 40 is an extended instruction on

how to communicate the good news in a way that it is heard as good by a traumatized people. In verse 2, the prophet is told to “comfort” God’s people and “speak tenderly” to them. But at the same time, in verse 9, the heralds of good news are instructed to “go up on a high mountain” and “lift up your voice with a shout, lift it up, do not be afraid.” Michael Chan sees in this passage a “primer on preaching”:

Isaiah 40:1–11 represents the very best kind of preaching. It is the kind of preaching that is grounded in proclamation and promise, but shaped fundamentally by careful listening to those things that afflict the hearts of his audience. Great preaching one might say involves two ears and one mouth. Like all of us, Second Isaiah was forced to preach to an audience that had experienced trauma and whose relationship to God had been deeply wounded as a result. For this audience, God’s hiddenness was far more real than God’s presence, and the preacher’s job, at least in part, is to point to those places where God is present (“Here is your God!” verse 9).

Osheta Moore challenges peacemakers to pursue peace by building others up as opposed to calling others out. She shares how she tries to humanize an issue by telling personal stories from her own experiences or the experiences of others. That is the comforting, tender side of the

how.

But there is also the “lift up your voice with a shout, lift it up, do not be afraid” side. And this is where Moore calls “

dear white peacemakers” to speak up and speak out on behalf of racial justice. To not be afraid to say the wrong thing or be guilty of “whitesplaining” but to use your voice to proclaim the good news that black lives matter—to you and to God.

I’m writing from my office at Keller Park Church in South Bend, Indiana, where I’m the teaching pastor. The sanctuary will be empty on Sunday when we stream our service. But while we haven’t gathered indoors as a church for worship for many months, our sanctuary is getting more use than ever.

Back in March 2020, when we received word that the South Bend Community Schools would be closing in light of the governor’s orders to shelter-in-place, we knew that meant that many of the kids in our neighborhood would go without adequate nutrition, since many of them rely on school meals throughout the week.

Even with the school corporation providing sack lunches at various pick-up locations throughout the city, many kids would go without a regular hot meal. And so, on March 16, 2020, our congregation

sprang into action.

Overnight we transformed our sanctuary into a food distribution center. We stacked chairs and put tables in their place. Boxes of cereal and bottles of water filled the front of the stage where music equipment once stood. Large roasters and to-go containers covered the ministry table. Bright colored masks made by volunteers found their place in the sound booth.

We assembled a small but dedicated team of food preparers and distributors from those of us who live in walking distance to the church. The rest of the congregation contributed by making donations to our new “COVID-19 response” fund on our website or by dropping off extra groceries in a cooler on the front steps of the parsonage.

For the first three months or so, we served three hot meals out of the church a week. In the summer months, we switched to one hot meal on Saturday mornings along with boxes of food for the week on Tuesdays and Saturdays.

On Thanksgiving day, knowing that many people wouldn’t be traveling to see family or wouldn’t have the means to prepare a traditional meal, the pastors and our kids along with another family made an assembly line in the sanctuary that served 125 Thanksgiving meals in an hour.

Some might look at this use of our space as a nice soup kitchen or food pantry but not the work of the gospel. But, for our neighborhood reeling from the physical and economic trauma we’re experiencing from the pandemic, a hot meal and a food box is the most tangible kind of good news we could offer.