Rice to bananas: How inflation has affected the prices of 5 grocery items in Singapore

Singapore has not been spared from rising prices worldwide, with its small and open economy that is reliant on global trade. ST PHOTO: KUA CHEE SIONG

Prisca Ang

DEC 3, 2021

SINGAPORE - The spectre of rising inflation looms large as global economies bounce back from the troughs of the Covid-19 pandemic and the supply chain crunch wears on.

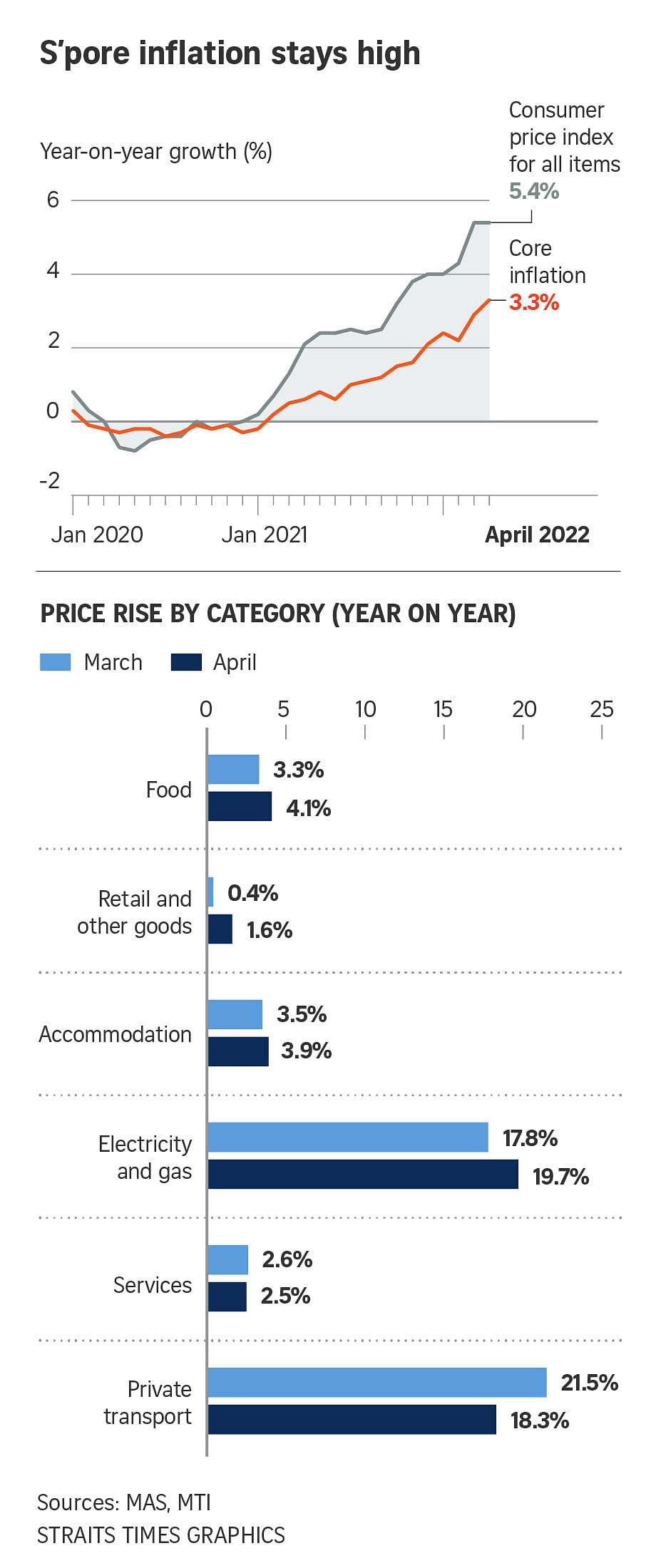

Singapore has not been spared, with

inflation hitting an eight-year peak in October - 3.2 per cent on a year-on-year basis - partly due to costlier cars and higher housing rents.

Core inflation, which excludes rents and private road transport costs,

climbed to 1.5 per cent - its highest in nearly three years.

This number better captures the underlying trend in consumer prices and is the measure the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) monitors most closely.

Inflation is not necessarily bad; a moderate amount generally reflects healthy economic growth. But persistently high levels of inflation can weaken consumer purchasing power and cut margins for businesses by depriving them of their pricing power.

Core inflation was buoyed in October by rising services and food prices and a smaller decline in the cost of retail and other goods.

Services costs rose at a faster pace due to pricier airfares and holiday expenses as border restrictions eased, while food inflation edged up as non-cooked food became more expensive.

Food prices have continued to climb every month on a year-on-year basis, even as core inflation was negative from February last year to January.

UOB economist Barnabas Gan said food prices are likely to inch up further if the Omicron variant triggers more supply chain disruptions.

"It might be somewhat similar to last year when Covid-19 was fresh in the picture. Back then, borders were closed and as a result, the prices of necessities, including food, were on the uptrend," he said.

But consumers might not feel the pinch of higher costs, added Mr Gan: "Omicron, which will likely be a growth dampener for the global economy, if not Singapore, will likely see some easing of energy prices... that could cushion food inflation in 2022."

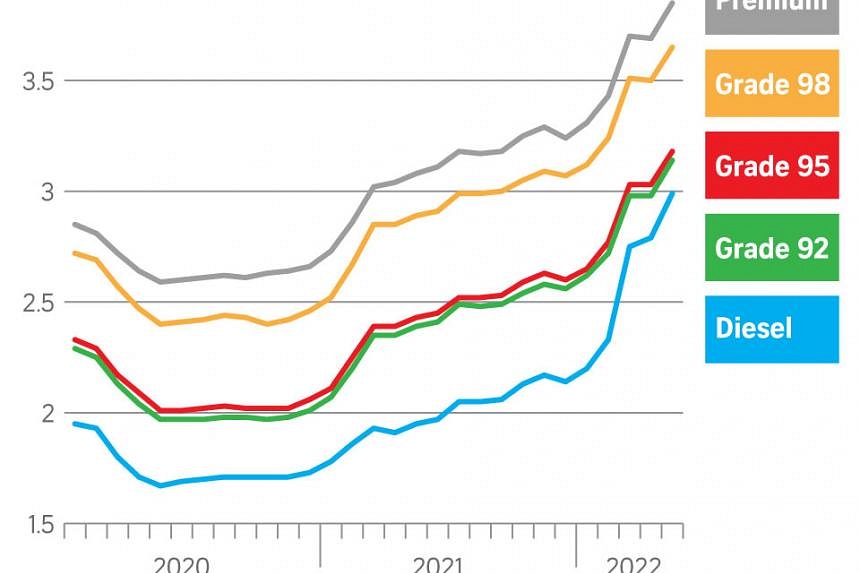

He noted that the

MAS tightened monetary policy in October and the gradually appreciating Singdollar could also help to cushion inflation, especially since Singapore imports most items, including food.

Ms Selena Ling, head of treasury research and strategy at OCBC Bank, said food inflation has generally picked up due to greater demand.

"This is partly due to more people working from home and also cooking, especially during the circuit breaker period when restaurants were closed, but also as the economy recovers."

Supply factors like border closures, weather changes from seasonal and climate change, and supply chain bottlenecks have also contributed to inflation, she added.

The Straits Times has looked at how the prices of several grocery products have changed over the past five years or so to get a flavour of how inflation has affected the cost of everyday items.

It traced the monthly average retail prices of rice, sea bass, bananas, kailan and fresh milk from 2017 to October 2021 using Singapore Department of Statistics (SingStat) data.

MORE ON THIS TOPIC

What is inflation, why is it rising now and how does it affect consumers?

Singapore's central bank 'ready to act' against inflation risks: Ravi Menon

Analysts said the prices of these items have largely remained stable over the years despite some fluctuations.

They also noted that the re-basing of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) from the base year of 2014 to 2019 has resulted in a clearer picture of prices faced by consumers.

The index - which measures the average price changes of a fixed basket of goods and services commonly purchased by resident households over time - is re-based every five years to reflect the latest consumption patterns.

1. Rice

Singapore imported US$277 million (S$378 million) worth of rice last year. PHOTO: UNSPLASH

Rice prices increased at an annualised rate of 1 per cent over the past five years, noted Assistant Professor of Finance Aurobindo Ghosh from the Singapore Management University's Lee Kong Chian School of Business.

The average retail price of 5kg of premium Thai rice - a long-time favourite of diners here - cost between $12.40 and $13.40 from January 2017 to April 2019.

Prices have generally risen to $13.20 or higher since then and crossed the $14 mark in April to June last year, peaking at $14.10 in May 2020, before falling.

Prof Ghosh said pandemic-induced travel and transportation restrictions, including during Singapore's circuit breaker, forced people to move indoors and created distribution bottlenecks: "This might have caused prices to go up due to supply chain issues."

Vietnam - the world's third largest rice exporter at the time - also implemented restrictions on its rice exports from late March to April 2020 to ensure it had sufficient domestic supplies to cope with the virus outbreak.

Singapore imported US$277 million (S$378 million) worth of rice last year, noted agriculture data platform Tridge.

Thailand supplied around 42 per cent of Singapore's total rice imports, followed by India at 22 per cent and Vietnam at nearly 19 per cent.

Singapore's Rice Stockpile Scheme ensures it has an adequate supply. It requires white rice importers to pre-commit the quantity they wish to bring in each month for local distribution.

They need to stockpile twice that amount in a government-designated warehouse, where rice can be kept for up to a year.

However, the scheme is unlikely to have a significant impact on prices, said Dr Cai Daolu, a visiting senior fellow at the National University of Singapore Business School.

"The global market for rice is highly competitive and Singapore is an open economy. Any surge in demand from Singapore can be met by global supply," he said.

"However, international prices of rice will increase if there's a surge of demand at a global scale."

2. Sea bass fish

Singapore imported 100,264 tonnes of fish last year, up from 94,590 in 2019. ST PHOTO: LIM YAOHUI

Sea bass prices have ranged from $11 to as high as nearly $13 per kg over the past five years.

Prices declined around 1 per cent on an annualised basis from 2017 to 2021, noted Prof Ghosh.

Mr Marc Laurence, general manager for Singapore and South-east Asia at food logistics company Seafrigo, said that chilled seafood needs to be flown in and air freight rates have surged amid the pandemic.

"The prices of agricultural products will always be linked to the season, whether it's a good harvest or not," he added.

Singapore imported 100,264 tonnes of fish last year, up from 94,590 in 2019, according to Singapore Food Agency data.

Vietnam, Indonesia and Malaysia account for over 60 per cent of these fish imports.

Festive demand during periods like Chinese New Year can also result in higher prices, said Prof Ghosh.

The price of sea bass surged to $12.99 in February 2018, before falling sharply to $10.99 the next month.

Prices have generally hovered at over $11 since March last year but they rose above $12 again in August and October this year.

"Supply chain disruptions and higher fuel prices might have caused some price impact," said Prof Ghosh.

The temporary closure of Jurong Fishery Port in July and easing of Covid-19 curbs in August that saw more people dining out could have helped the increase, he added.

3. Bananas

Bananas are among Singapore's top fruit imports. PHOTO: ST FILE

Bananas have hovered around $2.40 or more a kg since September 2019, up from $2.30 and above previously.

They rose by about 1 per cent annually over the past five years.

Bananas are among Singapore's top fruit imports, together with watermelons, papayas, navel oranges and Fuji apples.

There were 427,697 tonnes of fruit imported last year, down from 428,869 in 2019. Malaysia accounts for the lion's share of this, at 37 per cent.

Prof Ghosh said the prices of fresh fruit, including bananas, have risen amid supply chain disruptions coupled with greater demand as people adopt healthier lifestyles.

"Climate change also plays a significant role with more extreme weather patterns in many areas which grow bananas - typically in tropical areas like India, the Philippines and countries in Central and South America," he said.

Banana prices dipped in May 2020 to $2.25 before rising again.

Prof Ghosh said: "As banana is a perishable commodity, May and June 2020 might have seen excessive supply with producers expecting curbs due to the pandemic. This might have reduced the price."

4. Chinese kale (kailan)

Singapore imported 80,434 tonnes of leafy vegetables last year, up from 78,354 in 2019. ST PHOTO: JASON QUAH

Kailan fell from around $6 a kg at the start of 2017 to about $5 in early 2019.

Singapore's move to diversify its import sources and an increase in local production have shored up the supply of kailan and helped to bring down prices, said Prof Ghosh.

Dr Cai from NUS said: "Kailan prices are quite stable, but so is the price of rice and bananas. Given that Singapore can source vegetables from different locations, seasonal changes have very little effect on the domestic market."

Kailan has generally hovered around $5.20 to $5.25 since February last year.

Local production in hydroponic urban farms helps to mitigate seasonal changes in supply, said Prof Ghosh, adding that locally sourced vegetables are more sustainable.

"It travels (a shorter distance) to your dinner table, so it costs less and retains quality better," he said, noting that kailan prices have fallen about 3 per cent annually since 2017.

Singapore imported 80,434 tonnes of leafy vegetables last year, up from 78,354 in 2019.

Malaysia accounted for 64 per cent of the imports, followed by China at 24 per cent.

5. Milk

Singapore imports most of its dairy products from Australia, New Zealand and Thailand. PHOTO: ST FILE

Fresh milk had the largest price increase of the five items at nearly 4 per cent annually over the past five years.

"More discerning consumers are demanding organic milk sourced from places like Japan and Australia which is adding on to distribution cost. The cost of maintaining livestock might also add to the long-term price of fresh milk," said Prof Ghosh.

Singapore imports most of its dairy products from Australia, New Zealand and Thailand, according to Britain's Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board.

Mr Laurence from Seafrigo said the spike in freight prices has the largest impact on cheaper products like milk. "When we ship food that is already expensive and you add a bit of freight increase, the price increase is still manageable," he said.

"But on cheaper products, the freight has a huge impact."

Fresh milk prices rose to $3.20 a litre in January 2019, up from $2.70 to $2.90 previously.

They edged up further to $3.37 in April last year and have since remained around that level.

Prof Ghosh said: "With pandemic-related restrictions imposed in March 2020, supply disruptions due to the pandemic might have created bottlenecks for perishable products like milk. Prices stabilised as the restrictions were relaxed and alternative supply chains were established."