Rising costs: Your daily bread is going to be more expensive

The conflict in Ukraine has caused the price of flour, eggs and butter, ingredients in bread and pastries, to go up. ST PHOTO: LIM YAOHUI

Tan Hsueh Yun

Food Editor

PUBLISHED

Apr 30, 2022

SINGAPORE - Your daily bread, bagel, croissant, curry puff, pasta and pizza may cost more soon - if food businesses here can no longer absorb the increases in the prices of ingredients such as flour, eggs and butter.

The

logistics and supply chain disruptions that the pandemic wrought were just easing when the Russia-Ukraine war erupted.

Fuel prices have soared and supplies have been disrupted, prompting those same problems to come back with a vengeance.

Bakeries, restaurants, snack chains and home-based food businesses that use flour are feeling the pinch. Most are keeping prices steady and waiting to see what happens next.

Raise prices and they risk alienating customers, who are already cutting back on spending in a time of uncertainty.

Prices go up and up

Russia and Ukraine export a quarter of the world's wheat, The New York Times reported, and the ongoing war is causing

shortages and price increases.

Other factors are also impacting the supply of wheat, which is milled into flour. Weather disruptions have affected wheat production over the last two years, and adding to these woes are skyrocketing fuel prices.

Citing data from the International Monetary Fund, NYT reported that the price of wheat has spiked 80 per cent between April 2020 and December last year.

Singapore imports wheat from the United States, Canada, Japan, Italy, Vietnam and other countries, and businesses have been hit hard.

Curry puff chain Old Chang Kee, which has about 90 outlets, uses more than 50,000kg of flour each month, says chief financial officer Song Yeow Chung.

The flour, he adds, is from a local supplier and prices had gone up 10 per cent before the Russian invasion and are expected to rise another 10 to 15 per cent soon.

The supplier attributes this to the drastic increases in wheat prices and freight rates.

Mr Song says the company is looking at getting its supply from Indonesian and Malaysian flour mills.

Old Chang Kee had to pay 10 per cent more for flour before the Russian attack and prices are expected to rise again soon. PHOTO: OLD CHANG KEE

Chooby Pizza in Owen Road, which serves Neapolitan-style pizza, uses Italian flour for its pies and gets it from a local supplier.

Owner Mason Lim usually buys the flour in 25kg bags. But in the last two months, the supplier could sell him only 1kg retail bags as there was a shortage of packing materials for the larger bags.

The price hike was steep: In 25kg bags, the flour costs $2 a kg. In retail bags, it is $4.60 a kg, he says. Otherwise, the price of the flour has remained the same.

Home-based food business The Crane Grain buys its flour in 1kg bags because there is limited storage in baker Pah Qifan's home.

He has had to pay more for plain and cake flour, which he buys from baking supplies chain Phoon Huat and now pays 20 cents a kg more for them.

"Phoon Huat's prices for both types of flour had remained constant since late 2020 - even in the midst of supply chain disruptions from the pandemic - and it seems only fair it is increasing their prices now, on a par with inflation."

Heartland bakery The Pine Garden in Ang Mo Kio has seen an even steeper increase in the price of the flour from the US and Canada that it uses. Managing director Wei Chan says the price has gone up 19 to 30 per cent since the start of the year.

Simply changing brands of flour or suppliers is out of the question for most of these businesses.

Chooby's Mr Lim says: "I have tried using flours from different producers and suppliers, but have not managed to find any I'm happy with.

"Some issues include clumping due to poor storage and handling, making the flour difficult to mix and also causing dough and fermentation problems. Some flours also smell musty and unpleasant, and contain flour insects."

Changing suppliers is simply out of the question for heartland bakeries and home-based businesses. PHOTO: LIANHE ZAOBAO

For home-based businesses, it is often not practical to switch suppliers.

The Crane Grain's Mr Pah says: "For now, Phoon Huat is still the best option. It is also my main supplier for ingredients such as sugar, leavening agents and packaging materials. Having to deal with an additional supplier and hit its minimum order quantity for a home-based business would be more of a hassle."

Pastry chef Maxine Ngooi of Tigerlily Patisserie in Joo Chiat Road is paying 5 to 10 per cent more for the Japanese and French flour she uses.

"We have considered other sources, but it is difficult to switch because the premium quality of our bakes would be affected by the flour we use," she says.

Flour is not the only ingredient getting more expensive. The businesses interviewed here are also grappling with price hikes for ingredients such as butter, eggs, chicken, sunflower oil and coffee.

Mr Lim Yew Aun, chef and co-owner of The Cicheti Group, which has four Italian restaurants, says that while the price of the Italian flour they use has remained stable, he has seen a 20 per cent jump in the price of sunflower oil.

Ukraine and Russia are the

largest exporters of sunflower oil, Time magazine reported.

If the war continues, the price of snacks such as potato chips will also go up.

Ms Whang I-Wen, who runs home-based Able Bagel, says: "The biggest jump I've seen is in coffee prices - 1kg has gone up by $4. Dairy products such as butter has increased by a whole dollar per 250g. Cheeses are also more expensive, up by about $1 per kg."

Coping strategies

Some businesses such as Patisserie G are coping by cutting products and careful logistics planning. PHOTO: PATISSERIEG/FACEBOOK

Still, businesses are reluctant to pass on the costs to consumers.

Ms Gwen Lim, who runs the Patisserie G chain and also B.A.O. or Bakery Artisan Original, which supplies bread to food businesses, buys flour from Malaysia, Vietnam and France.

Prices started going up in September last year, by 7 to 15 per cent.

For the patisserie business, she is streamlining the number of products and cutting out the ones that do not sell well, planning logistics more carefully to save on fuel costs, and bringing in equipment and machinery to deal with rising staff costs.

Old Chang Kee's Mr Song says: "We treasure our customers a lot and will increase prices only if we have no choice. Our past records show that our price adjustments are usually in a conservative range of 10 to 20 cents.

"Currently, our strategy to counter rising costs and maintain prices is to invest in branding, information technology, machinery, and new product innovations. Our fixed costs, such as rental and labour, are substantial, so doing this helps increase our sales per outlet and alleviate the fixed-cost pressures."

Home-based outfits are also trying to keep costs manageable without increasing prices.

Ms Whang says: "I try to buy my ingredients in bulk if they're not perishable. I also stock up when an ingredient goes on sale, so we can keep costs as low as possible."

Mr Xavier Lee, who runs pastry business Flourcrafts, adds: "I order less perishable ingredients in bulk, with friends in various patisseries so we can also reach the tiers for discount and delivery.

"I'm encouraging customers to place pre-orders, arranging specific windows of collection so I can minimise food wastage and also manage production and the running cost of electrical equipment like the oven."

Humble Bakery, which started in September last year, is known for its scones and burnt cheesecakes. It is grappling with a 20 per cent price hike for eggs, and also paying more for butter, cream, electricity and delivery charges.

Co-founder Tan Zhuo Guan says: "We are a very small establishment and a price increase can hurt our sales. We can only continue to take in pre-orders, monitor and absorb the price increases at the moment, and hope to get more sales to cover the rising overheads."

Mr Daniele Sperindio, group executive chef of the Il Lido group of Italian restaurants and bars, says: "We engineer our operations to become leaner and more efficient. We collaborate with suppliers and importers to share the pain of price increases, and find new creative ways to transform humble ingredients.

"Occasionally, we simply absorb the increased costs, thinning our margins and waiting for better times to come."

If prices of ingredients continue to increase, the cost will have to be passed on to customers. PHOTO: ST FILE

Trigger point

What if better times never come?

Ms Lim of Patisserie G says: "I am watching closely what happens with the war in Ukraine. I believe prices may go up by 20 per cent or more. If so, we will have to pass it on to the consumers. And it will be quite immediate."

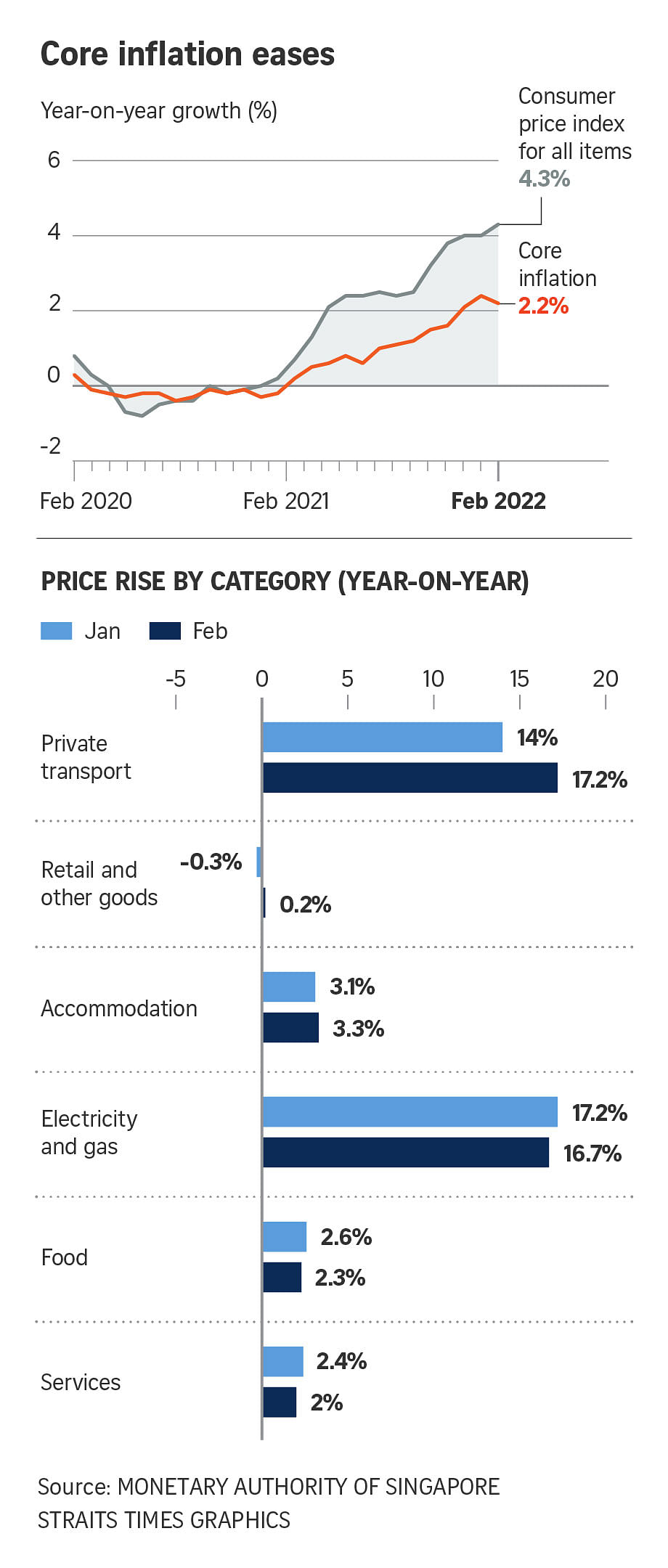

Mr Guillaume Pichoir, chief executive of Da Paolo Group, adds: "We are generally looking to align our prices to current inflation levels. Most of our operation costs have become much higher. Most recently, electricity prices have been skyrocketing, manpower costs are a major concern, and freight prices have increased for all imported goods."

Japanese bakery chain Gokoku says the price of the Japanese flour it uses has risen by more than 17 per cent, along with the prices of eggs, dairy products, dried fruit, packaging and utilities. Labour costs have also gone up 20 per cent since the pandemic started.

A spokesman says the company would review the situation in the second or third quarter, and if there is a price increase, it would be in the 10 to 30 cent range.

"At the moment, we are absorbing the increase in raw material costs. However, this is not sustainable in the long term.

"In order to continue providing the quality products Gokoku is known for, we have to review our pricing to stay competitive."