No one should die alone, be left undiscovered for weeks

Apart from tackling reclusiveness, we should also look at shoring up companionship in the last moments

Sng Hock Lin

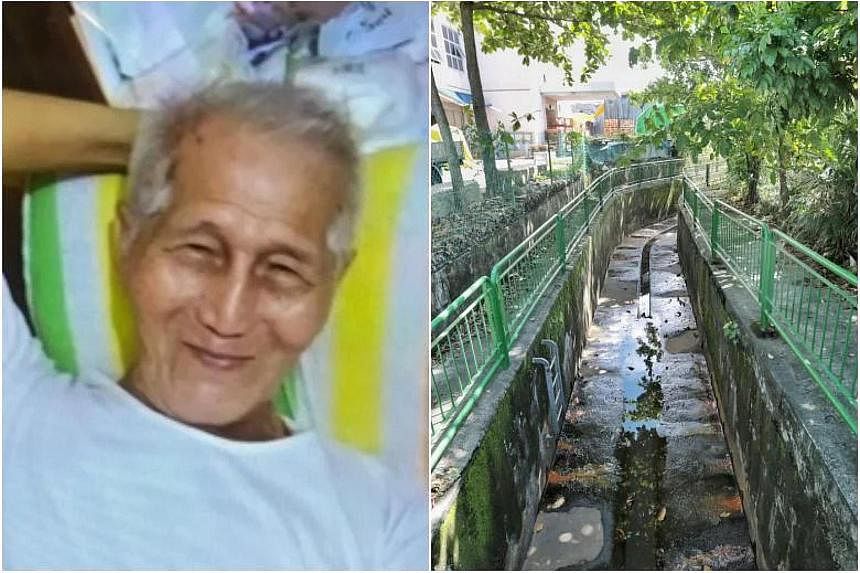

Beyond governmental and policy changes, the biggest impact must come from community action to tackle social isolation problems, says the author. PHOTO: ST FILE

NOV 28, 2022

Recent news of a reclusive pair – an elderly man and his mother –

who were found dead in a flat sent shockwaves across Singapore.

It spoke volumes of the decline in neighbourly relations and raises questions over whether we have failed our seniors as a society.

The news is heartbreaking. As social creatures who surround ourselves with loved ones during major life events, this need for companionship is even more urgent for someone near death. Fear of the unknown and the finality of life in those last moments can be terrifying, particularly if the person dies from a traumatic event like a heart attack.

News such as that of the elderly couple make us anxious about our own future and mortality, more so because we know that reports of such incidents will only increase and fear that a lonely death could await us as well. In a study by the Ministry of Health (MOH) and National University of Singapore (NUS), the number of seniors living alone is projected to increase by four times from around 70,000 in 2020 to 210,000 in 2060.

Changes in demographics and family structure explain this trend, but individual choices also play a part. Either by choice, estrangement from family or because they are childless, it is commonplace to see seniors live by themselves in older estates like Bukit Merah and Queenstown.

Younger seniors in their 60s are still fit and healthy, but their sight, hearing and sense of touch may begin deteriorating as they approach their 70s and 80s. Those fiercely independent who insist on continuing to live by themselves will find it increasingly difficult to carry out activities of daily living unaided. This could include eating, bathing, moving around and other actions that they used to take for granted. Many keep their problems to themselves for fear of inconveniencing others.

This fear of inconveniencing others seems like a common but unhealthy two-way dynamic. In Singapore, knocking on the door of a reclusive senior can be awkward, especially if people barely speak to one another.

Neighbours tend to be cordial, but keep to boundaries. Fewer are exchanging greetings or striking up casual conversations like before, according to a survey by HDB released in February 2021. What started out as respect for privacy and social distancing during Covid-19 can morph into benign avoidance.

So, in spite of desiring some company, lonely seniors stay away for fear of troubling others, and neighbours do likewise to avoid irritating one another.

Hospice programmes such as those run by Assisi Hospice and HCA Hospice Care offer a way out of the problem.

Assisi Hospice’s

No One Dies Alone programme provides company to those without friends and family in their final hours. Volunteers befriend them and take on shifts to keep them company as signs emerge that they may soon pass away. Palliative care specialists call this the “active dying period” when people tend to communicate less, sleep more and eat less.

One of Singapore’s largest hospice care providers, HCA Hospice, also offers a Vigil Angels service providing respite to caregivers by accompanying the dying.

Still, the challenge is the limitation of these services to patients already enrolled into such hospice programmes. They may not be accessible to the reclusive who keep to themselves.

Lonely deaths in Japan

Global examples show pre-empting seniors dying alone requires a whole-of-society effort to tackle reclusiveness. In rapidly ageing Japan, solitary deaths, called “kodokushi”, have become such a major public concern that the government

appointed its first Minister of Loneliness Tetsushi Sakamoto in 2021 to work with multiple official agencies to stem social isolation.

Japan discovered an alarming fact: “Hikikomori”, or the acute social withdrawal rate, was growing, with people sometimes not leaving their homes for months at a time, citing a fear of social interactions and feelings of inadequacy or even depression. Japanese mental health experts have estimated there could be

up to two million people affected by hikikomori, with half of those middle-aged or elderly.

The problem is compounded by the emergence of “ghost towns”. Decades ago, fuelled by the post-war economic boom, Japan built large public housing projects outside major cities like Osaka and Tokyo. These vast, concrete complexes now lie empty as adult children move out of their homes and precincts are deserted, with ageing inhabitants left to fend for themselves.

The same is happening in Hong Kong and China. Could it also happen in Singapore in older estates?

Ageing-in-place

Kampung Admiralty, which was completed in 2017, is Singapore’s first integrated housing development. PHOTO: ST FILE

Singapore has sought to innovate with new housing models to cater to an ageing population. In 2017, the

first integrated housing development, Kampung Admiralty, was completed. It incorporates housing for the elderly with a wide range of social, healthcare, communal, commercial and retail facilities. More such models,

like Yew Tee Integrated Development, are set to follow.

These “vertical kampungs” encourage healthy community living by co-locating childcare and eldercare services and sports facilities.

Steps have also been taken to enliven existing estates where many seniors live. The Community Networks for Seniors programme under MOH and its Agency for Integrated Care (AIC) brings together different stakeholders – voluntary welfare organisations, People’s Association’s (PA) grassroots organisations, health services and government agencies – to jointly engage and support our seniors.

These aim to extend befriending services to seniors living alone, and provide health and social support for those with acute needs. Under the National Healthcare Group, for example, there are Wellness Kampung and Share-a-Pot programmes to empower seniors to lead others in exercise and healthy eating.

Beyond governmental and policy changes, however, the biggest impact must come from community action to tackle the social isolation problems.

Turning again to Japan, local organisations like Hocchi-No-Lodge, in the town of Karuizawa, provide care and organise social activities, which includes a gym, cafe, arts and cultural events to engage residents, as well as support the creation of interest groups and hobby clubs. These go beyond meeting immediate needs to promote well-being.

In Boston, a group of older adults pioneered Beacon Hill Village – a community network promoting fitness services, social bonding and networking through volunteerism, peer-to-peer and self-leadership activities. Residents mobilise older adults to serve fellow senior neighbours. By putting older people in the centre, the model reframes them as assets rather than liabilities, empowering them as catalysts of change in intervention strategies.

They have taken their cue from the Ibasho principles of Japan which put seniors at the core. Empowering older adults in self-leadership, and making them feel valued can bolster a sense of identity, belonging and meaning in their lives.

The concept has garnered a movement – a “village movement” – moving the narrative of ageing as one of “ageing-in-place” and therefore ageing as something to be tolerated, to “ageing-in-community” where longevity is a resource to be harnessed for greater contributions to society.

Yet despite the growing popularity of this movement, greater institutional partnerships with the public and private sectors, and healthcare providers will be needed to tackle the challenge of “hikikomori.”

Recreate the kampung spirit

A strong community ethos is similarly alive in Singapore. We call it the kampung spirit and can see it most visibly in older towns like Chinatown where many seniors gather.

There may be nuances across neighbourhoods. A survey some years back by the National University Health System of elderly people living in Chinatown and Toa Payoh districts showed more living in Chinatown were happy and satisfied with life (71 per cent), compared with Toa Payoh (69 per cent).

Because of the small spaces of their rental flats in Chinatown, dwellers tend to gather outside to meet friends in the community centres or void decks and create strong relationships. In contrast, Toa Payoh seniors living in bigger flats did not interact as much with neighbours and seemed more isolated and lonelier.

Seniors gathering at an open space at Chinatown Complex on June 23, 2022. PHOTO: ST FILE

There are various senior interest groups in Singapore trying to break this isolation. The PA Wellness Programme offers seniors a wide variety of activities keeping them mentally, physically and socially active. SportSG’s Team Nila, a sports volunteers group, started a Silver Champion movement to promote senior volunteerism. Apart from exercises, they also plant vegetables within ActiveSG Sport Centres and share their harvest with the needy.

The Lion Befrienders and Society of St Vincent de Paul are also doing a good job befriending and visiting the homes of the elderly.

More collaboration among agencies and grassroots organisations could support the growth of these networks to be a force for doing good for seniors, especially those needing assistance.

Based on my research, many have benefited physically and mentally from such social interactions, but more work is needed to understand factors preventing the recalcitrant and reclusive from participating.

Recreating this kampung spirit must be a priority for an ageing Singapore. The pandemic has exposed the dangers of vulnerable seniors left to their own devices as neighbours around them busy themselves. A survey by Singapore Management University’s Centre for Research on Successful Ageing (Rosa) completed in 2020 showed the number of seniors feeling satisfied with life dropping, with those living alone feeling more isolated socially.

Early warning

At the very least, we need early warning indicators of seniors in crisis. Technology can be an enabler.

Security firm Aetos and CoNEX, a healthcare company, have deployed predictive AI-enabled technology platforms for non-intrusive monitoring of seniors at home. These leverage round-the-clock monitoring and a front-line responder network to facilitate timely interventions when anomalies such as falls are predicted and detected.

The community could be enlisted to act as additional eyes and ears looking out for our seniors. Senior engagement should be expanded to include intergenerational volunteers. Corporations and schools could consider adopting a village concept to have employees volunteer at specific senior activity centres or active ageing hubs beyond episodic events during holidays.

Front-line government agencies such as PUB can monitor the daily utility consumption of seniors living alone in flats to track anomalies. Postmen can sound the alarm when spotting uncollected mail in postboxes, and cleaners should alert someone if junk mail piles up at the doors of senior dwellers.

There may also be new demand for platform companies from this ageing economy. Delivery workers can be human sensors or play extended community liaison roles running errands for seniors, escorting them to doctors, or delivering medicine. From GrabFood, we could have GrabCare.

Each of us has a part or more to play if we don’t want another lonely death. Singapore needs to step up now.

- Sng Hock Lin is pursuing his PhD in gerontology at the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS)