Chinese American WWII vets remember Flying Tigers days

Last week, Chinese American World War II veterans of the legendary Flying Tigers reunited for their 68th Anniversary in New York City. Their all-Chinese American units served a special mission: to assist American Flying Tigers pilots and train Chinese Air Force ground crews to defend against Japanese invasion. They flew the "Hump" (the lower range of the Himalayan mountains), drove the legendary Burma Road, performed troop transport, repaired planes, and did crash recovery.

Now ranging from 86 to 93 years in age, these veterans came from across the country to bond and reflect. At the American Legion Kimlau Post 1291 in Chinatown, the first Chinese-American American Legion Post established after the war, they met friends and traded stories. A panel shared their experiences to a capacity crowd at the Museum of Chinese in America, where a short film featured photos of the men handsomely donning their American G.I. uniforms. They reminisced on the 1940s, when their uniforms first brought to them a sense of equality and pride.

World War II marked many milestones for Chinese Americans. Most significantly, defense and other mainstream jobs became available, freeing Chinese Americans who had been confined solely to restaurants and laundries. The Montgomery G.I. Bill helped them afford education. Chinatowns transformed from bachelor communities to family communities, with the help of a special War Brides Act passed by Congress that enabled Chinese Americans to legally bring their brides over from China. Any soldier who served a minimum of 90 days gained citizenship, even if he had entered the country illegally.

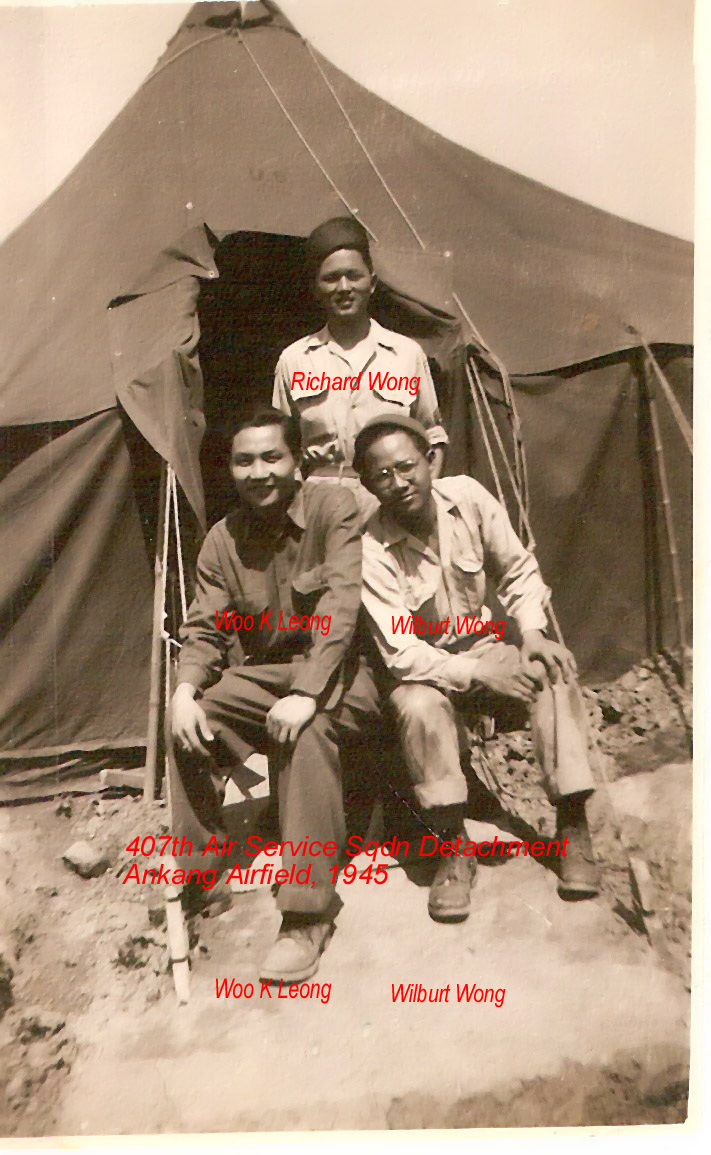

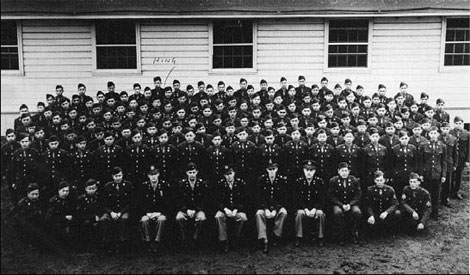

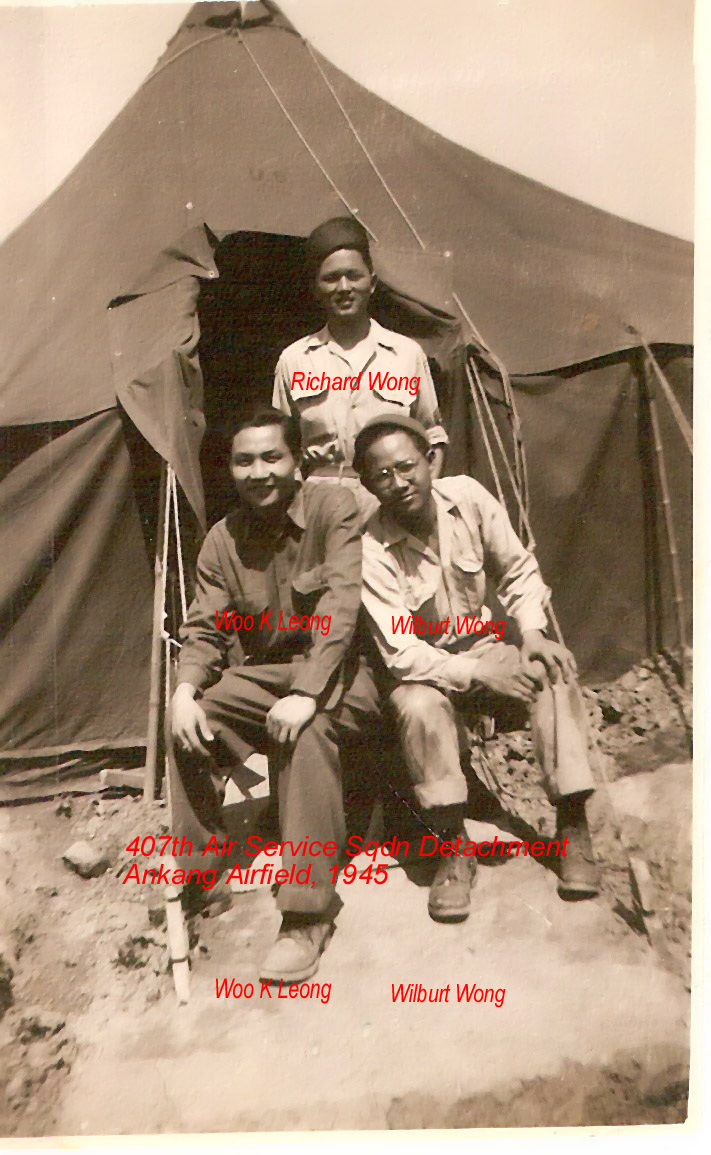

It's been all but forgotten that 20,000 Chinese Americans served in World War II. 61 percent of those who served were born in America, 39 percent from a foreign country. It is astonishing that in New York City alone, 40 percent of all Chinese Americans between 18 and 36 enlisted or were drafted -- the highest ratio among any national grouping in the country. Because some of the drafted and enlisted were "paper sons" who came to America with falsified papers, many of the men were actually younger or older than the legal age to serve. In one of the all-Chinese American units, the 407 Air Service Squadron, the actual age of the men ranged from 15-50.

91-year-old Mack Pong who was born in Houston, Texas, graduated high school in 1938. "When I finished high school, in 1938, I couldn't get a job. They didn't want Chinese. Finally, I got a job at the post office, because they needed people, [after] so many were drafted."

Eventually, Pong himself was drafted in 1943 and put in a unit of 250 Chinese Americans, which later formed the 407 Air Squadron Group of the 14th Air Service Group. They trained in Patterson Field, OH, and made their way to Calcutta. "Our group was formed, so we had to pick up supplies. Outside Calcutta was Kanchrapara, which was a service depot -- they had all the supplies. We had to pick up stoves for the kitchens, mechanical ware for the mechanics, food, practically everything to suffice, to make it self-serving. That was tough, because they had no cranes, and everything was transported by hand. Everything was moved onto a steamer ship on Brahmaputra River, then we had to take it off the boat, and put it on a narrow gauged railroad. Then we set up a base and squadron in operation at Dinjan."

After the war, the Chinese American soldiers promised to keep in touch and make something of their lives with their newfound rights. Over the years, Mack Pong kept in contact with at least 175 of the 250 Chinese American comrades, mostly those on the West Coast, from his 407 Air Service Squadron. Later, friends from the 987th Signal Company joined as well. Richard Chin of New York City, who passed away this year, kept in contact with those on the East Coast. Their initial reunions were informal dinners where the men drank and smoked cigars at the San Francisco VFW Hall. By the 60s, they brought their wives, and by the 80s, the reunions became family events.