www.channelnewsasia.com

CNA Insider

After the private tuition ban, is it still all work and no play for pupils in China?

After the private tuition ban, is it still all work and no play for pupils in China?

Christy Yip , Tang Hui Huan & Tang Fan Xi

06 May 2023 06:01AM (Updated: 07 May 2023 10:22PM)

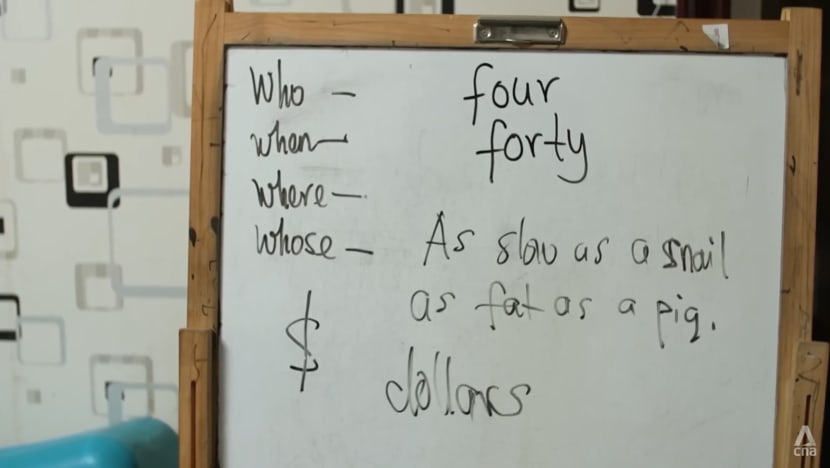

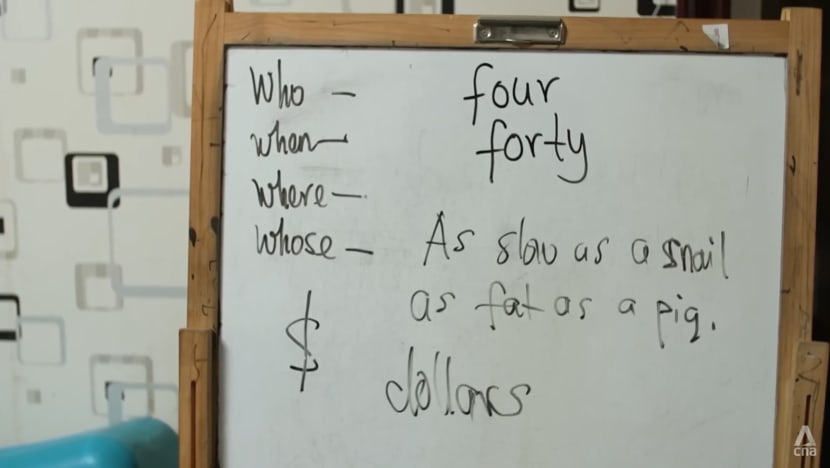

BEIJING: During school holidays, eight-year-old Zaizai is sent to live with his English tutor — sometimes for 10 days, sometimes for a month. His two-year-old sister tags along for exposure to the language.

It matters little to their mother, Lu Ai, that this arrangement is illegal.

Since July 2021, private tuition over weekends and holidays has been banned for Chinese students below 16. No new licences have been issued for academic tuition centres, while existing centres had to register as non-profit institutions. Schools have also had to reduce daily homework.

The policy, known as “shuang jian”, or double reduction, is aimed at easing pressure on students in China’s notoriously stressful educational system.

Pupils in China go through nine years of compulsory education.

Pupils in China go through nine years of compulsory education.

It is meant to “restore education as a public good”, so that doing well does not depend on one’s means, said Hou Yuxin from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

Well-intentioned as the ban may be, however, it has only sent the industry underground and the fees sky-high. The programme Undercover Asia examines how anxious parents continue to fuel demand for tuition.

As a result, there had been a deluge of advertisements on billboards and televisions, preying on parents’ anxiety for their children to succeed.

Advertisements for tuition services lined the streets in China.

Advertisements for tuition services lined the streets in China.

One slogan in particular sticks in Joel Dewald’s mind, from an advertisement for New Oriental Education, the first of its kind in China to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange. It went: “Let us train your children, or we’ll train their competitors.”

The former enrichment centre owner said: “They played on people’s fear of getting left behind.”

Indeed, former tuition salesperson Li Miao said this line of work often “made use of” parents’ anxiety to reel them in.

Even with the tuition ban, their anxiety remains. These days, one of the ways to find a tutor is by word of mouth. And from what Lu knows, “good tutors are fully booked for the next few years”.

To find a suitable English tutor for Zaizai, she took to asking friends for recommendations at every chance she got; she even asked foreigners on the street if they taught English. The process took about one and a half years.

Lu Ai with her son, Zaizai.

Lu Ai with her son, Zaizai.

To parents like “Yuan Mei”, who did not want her real name to be disclosed, the double reduction policy was a welcome relief at first.

She thought it would be enough for her son, who is 15 this year and due to sit his Zhongkao (senior high school entrance examination), to just study within school hours.

“I thought everyone could be at the same starting line, (that) grades would depend on the children being attentive in class and working hard,” she said. But the fear of her son missing out caught up with her.

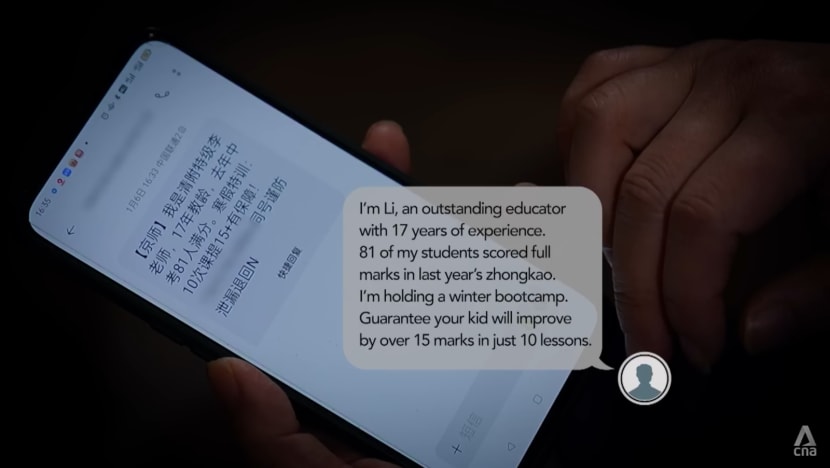

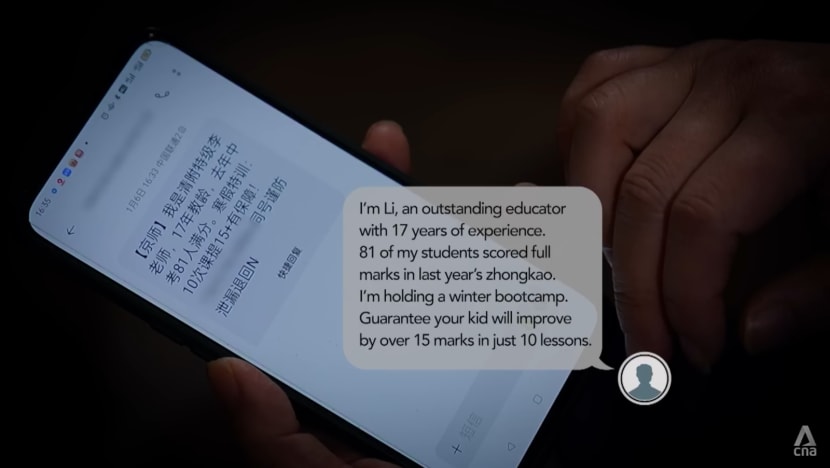

Since the ban, Yuan has often received text messages from tuition companies advertising their services. She “usually rejected” the offers, but when a “famous maths teacher” reached out, she was “tempted”.

An example of the text messages “Yuan Mei” received from tutors marketing their services.

An example of the text messages “Yuan Mei” received from tutors marketing their services.

“Some teachers teach better. They may need to explain for just five minutes. What if we meet a teacher like that, and my son is instantly enlightened?” she said.

She eventually passed on maths tuition but signed up her son for English tuition, found through a friend’s recommendation, as he was struggling with that subject.

“Everyone’s secretly sending their children to tuition,” said Yuan.

Parents said the ban has also made tuition more expensive and widened the gap between the haves and have-nots, which is the very thing the ban aimed to bridge.

Group classes have all but ceased, while the cost of one-to-one tutoring has increased.

In first-tier cities like Beijing and Shanghai, some one-to-one tutors are charging as much as 3,000 yuan (US$430) an hour. That is at least ten times more than before and about a quarter of the average monthly wage for white-collar workers in these cities.

For this reason, Gong Erkang has stopped sending his children, one in first grade and the other in fifth grade, for tuition even as he suspects they are not doing as well in class as before.

“I feel helpless,” said Gong, a video editor. “In the past, I could send my children to mass tuition classes, but now there’s nothing.”

Monthly tuition fees used to cost a few hundred yuan, but now each session “is already several times (costlier than) that”, he said. “Double reduction affects ordinary families the most. Rich families will always be able to find other ways.”

For one thing, there are “too few paths” for students after streaming, said Chen Zhiqin, an educational software developer.

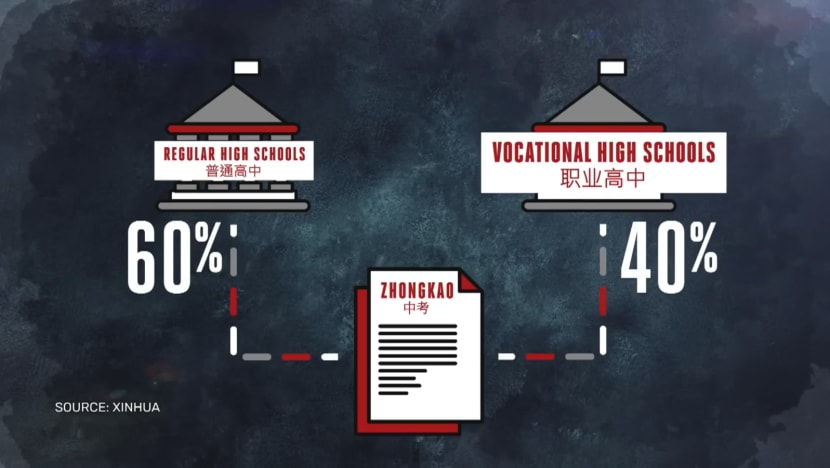

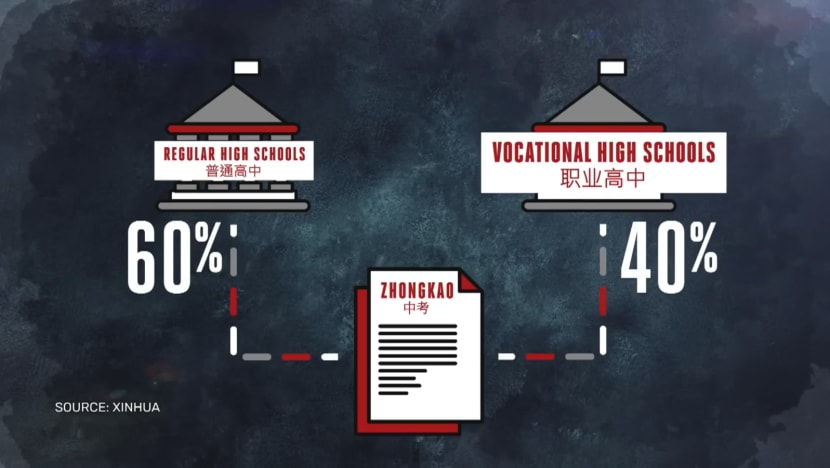

One’s grades in the Zhongkao, for example, determine whether one continues in academics or enters vocational school. Students who did not do well go to the latter and are taught technical skills for employment, such as hairdressing and catering services.

To some parents, the choice is as good as none, seeing that vocational schools have been stigmatised in the country for a long time.

Past distribution of Zhongkao candidates.

Past distribution of Zhongkao candidates.

“If a child enters high school, even if it isn’t an elite one, there’d be a good learning environment. But if (children) enter vocational institutions, they’d basically stop learning,” said Yuan.

Hoping to boost the image of vocational schools, China revised the Vocational Education Law last year.

It now states that vocational and general education are equally important and that China encourages the development of various forms of vocational education, Xinhua News Agency reported. This was the first major revision of the law in 25 years.

But parents such as Yuan will not be moved. “Many parents know vocational education doesn’t get the same emphasis,” she said.

In any case, few children actually need tuition, said Chen. But many tuition centres had pushed students to learn beyond their curriculum ahead of the high school and university entrance exams.

“They brought forward the starting line from high school to middle school to even elementary school,” said Chen. “They were swept into a rat race with content not suitable for them.

The double reduction policy was intended to reduce the burden of academic competition, but as far as Lu is concerned, it has achieved the opposite. She believes parents must “put in more effort”.

She first sent her son for tuition and enrichment classes at the age of five, after realising that some of his peers could already communicate in English while he “didn’t know anything”.

Lu could help Zaizai with most academic subjects, except English.

Lu could help Zaizai with most academic subjects, except English.

“It was a huge blow to me,” said Lu, who worried that he would lose out to his peers later in life if she did not intervene promptly.

“If parents feel that their child’s development depends on him, they’re very irresponsible. They don’t have their priorities sorted.”

https://www.channelnewsasia.com/cna...7sdnXvhaK7X6OfUaz9PEFYvM5CAvSJOeJy5e3ZlU6CrcY

CNA Insider

To reduce academic stress, China banned private tuition. Has the policy backfired?

After private tuition over weekends and holidays was banned, the academic tutoring went underground — at sky-high rates available only to those with time and money. CNA’s Undercover Asia looks at how anxious parents continue to fuel demand.

Christy Yip , Tang Hui Huan & Tang Fan Xi

06 May 2023 06:01AM (Updated: 07 May 2023 10:22PM)

BEIJING: During school holidays, eight-year-old Zaizai is sent to live with his English tutor — sometimes for 10 days, sometimes for a month. His two-year-old sister tags along for exposure to the language.

It matters little to their mother, Lu Ai, that this arrangement is illegal.

Since July 2021, private tuition over weekends and holidays has been banned for Chinese students below 16. No new licences have been issued for academic tuition centres, while existing centres had to register as non-profit institutions. Schools have also had to reduce daily homework.

The policy, known as “shuang jian”, or double reduction, is aimed at easing pressure on students in China’s notoriously stressful educational system.

It is meant to “restore education as a public good”, so that doing well does not depend on one’s means, said Hou Yuxin from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

Well-intentioned as the ban may be, however, it has only sent the industry underground and the fees sky-high. The programme Undercover Asia examines how anxious parents continue to fuel demand for tuition.

RELIEF AT FIRST, THEN FEAR CATCHES UP

Hou himself used to be in the private education sector, as vice president of Yaqiao Education Group, and said private tutoring had been hijacked by profit-making.As a result, there had been a deluge of advertisements on billboards and televisions, preying on parents’ anxiety for their children to succeed.

One slogan in particular sticks in Joel Dewald’s mind, from an advertisement for New Oriental Education, the first of its kind in China to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange. It went: “Let us train your children, or we’ll train their competitors.”

The former enrichment centre owner said: “They played on people’s fear of getting left behind.”

Indeed, former tuition salesperson Li Miao said this line of work often “made use of” parents’ anxiety to reel them in.

Even with the tuition ban, their anxiety remains. These days, one of the ways to find a tutor is by word of mouth. And from what Lu knows, “good tutors are fully booked for the next few years”.

To find a suitable English tutor for Zaizai, she took to asking friends for recommendations at every chance she got; she even asked foreigners on the street if they taught English. The process took about one and a half years.

To parents like “Yuan Mei”, who did not want her real name to be disclosed, the double reduction policy was a welcome relief at first.

She thought it would be enough for her son, who is 15 this year and due to sit his Zhongkao (senior high school entrance examination), to just study within school hours.

“I thought everyone could be at the same starting line, (that) grades would depend on the children being attentive in class and working hard,” she said. But the fear of her son missing out caught up with her.

Since the ban, Yuan has often received text messages from tuition companies advertising their services. She “usually rejected” the offers, but when a “famous maths teacher” reached out, she was “tempted”.

“Some teachers teach better. They may need to explain for just five minutes. What if we meet a teacher like that, and my son is instantly enlightened?” she said.

She eventually passed on maths tuition but signed up her son for English tuition, found through a friend’s recommendation, as he was struggling with that subject.

“Everyone’s secretly sending their children to tuition,” said Yuan.

Parents said the ban has also made tuition more expensive and widened the gap between the haves and have-nots, which is the very thing the ban aimed to bridge.

Group classes have all but ceased, while the cost of one-to-one tutoring has increased.

In first-tier cities like Beijing and Shanghai, some one-to-one tutors are charging as much as 3,000 yuan (US$430) an hour. That is at least ten times more than before and about a quarter of the average monthly wage for white-collar workers in these cities.

For this reason, Gong Erkang has stopped sending his children, one in first grade and the other in fifth grade, for tuition even as he suspects they are not doing as well in class as before.

“I feel helpless,” said Gong, a video editor. “In the past, I could send my children to mass tuition classes, but now there’s nothing.”

Monthly tuition fees used to cost a few hundred yuan, but now each session “is already several times (costlier than) that”, he said. “Double reduction affects ordinary families the most. Rich families will always be able to find other ways.”

"SNEAKY COMPETITION WILL PERSIST"

The crux of the problem, experts agree, is the intense competition in schools.For one thing, there are “too few paths” for students after streaming, said Chen Zhiqin, an educational software developer.

One’s grades in the Zhongkao, for example, determine whether one continues in academics or enters vocational school. Students who did not do well go to the latter and are taught technical skills for employment, such as hairdressing and catering services.

To some parents, the choice is as good as none, seeing that vocational schools have been stigmatised in the country for a long time.

“If a child enters high school, even if it isn’t an elite one, there’d be a good learning environment. But if (children) enter vocational institutions, they’d basically stop learning,” said Yuan.

Hoping to boost the image of vocational schools, China revised the Vocational Education Law last year.

It now states that vocational and general education are equally important and that China encourages the development of various forms of vocational education, Xinhua News Agency reported. This was the first major revision of the law in 25 years.

But parents such as Yuan will not be moved. “Many parents know vocational education doesn’t get the same emphasis,” she said.

In any case, few children actually need tuition, said Chen. But many tuition centres had pushed students to learn beyond their curriculum ahead of the high school and university entrance exams.

“They brought forward the starting line from high school to middle school to even elementary school,” said Chen. “They were swept into a rat race with content not suitable for them.

If the country’s talent selection mechanism doesn’t change, this sneaky competition will persist.”

The double reduction policy was intended to reduce the burden of academic competition, but as far as Lu is concerned, it has achieved the opposite. She believes parents must “put in more effort”.

She first sent her son for tuition and enrichment classes at the age of five, after realising that some of his peers could already communicate in English while he “didn’t know anything”.

“It was a huge blow to me,” said Lu, who worried that he would lose out to his peers later in life if she did not intervene promptly.

“If parents feel that their child’s development depends on him, they’re very irresponsible. They don’t have their priorities sorted.”

https://www.channelnewsasia.com/cna...7sdnXvhaK7X6OfUaz9PEFYvM5CAvSJOeJy5e3ZlU6CrcY