- Joined

- Sep 22, 2008

- Messages

- 80,521

- Points

- 113

The vegetarian 'meat' aimed at replacing the real thing

By Laura WellesleyChatham House

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Meat-free foods that "bleed" like the real thing are becoming increasingly common. Could these vegetarian alternatives replace "traditional" burgers and sausages?

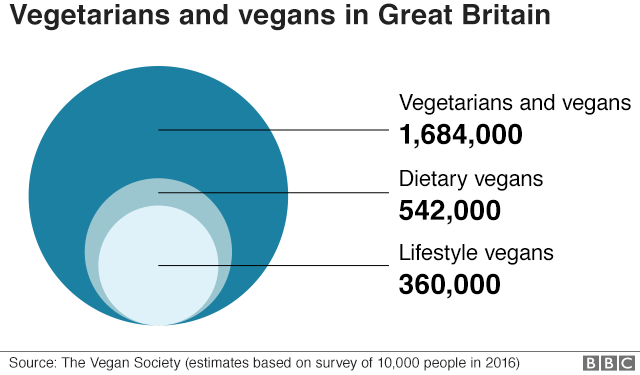

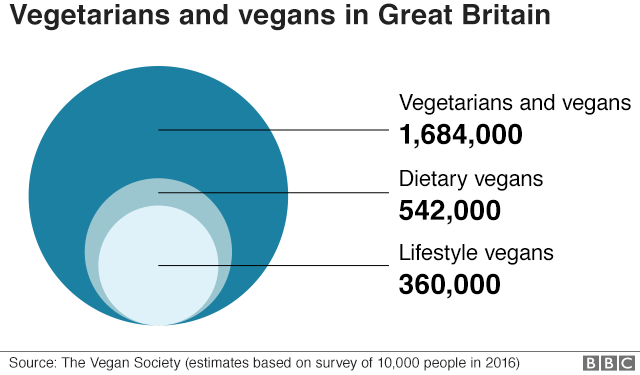

Concerns about the environmental and health impact of our diets has seen interest in vegetarian and vegan foods grow.

This has boosted everything from flexitarianism to vegan sausage rolls and campaigns like "Veganuary".

While Quorn and Linda McCartney once ruled the meat substitute aisles of our supermarkets, new companies are appearing with a radically different vision of "meat-free".

Vegetarian "meat" designed to mimic the look, smell and taste of the real thing are already available, while scientists are developing lab-grown meats

ADVERTISEMENT

But with the arrival of these new dishes comes an increasingly animated debate about what can be called "meat", as well as how - and even if - it should be sold.

The first type of these new meat alternatives are plant-based products.

These are already available in restaurants, pubs and supermarkets, contributing to a growing market worth an estimated £4.6bn. Last week, the value of US firm Beyond Meat rose to nearly $3.8bn (£2.9bn) after its Wall Street debut.

The aim of plant-based "meat" is for it to be so similar to cook and eat as the real thing, that it is virtually indistinguishable.

It is made from plant proteins - usually wheat, pea or potato. Natural colourings like beetroot juice usually provide the "blood".

Another US firm, Impossible Foods, has developed a plant version of heme - which gives beef its colour and taste.

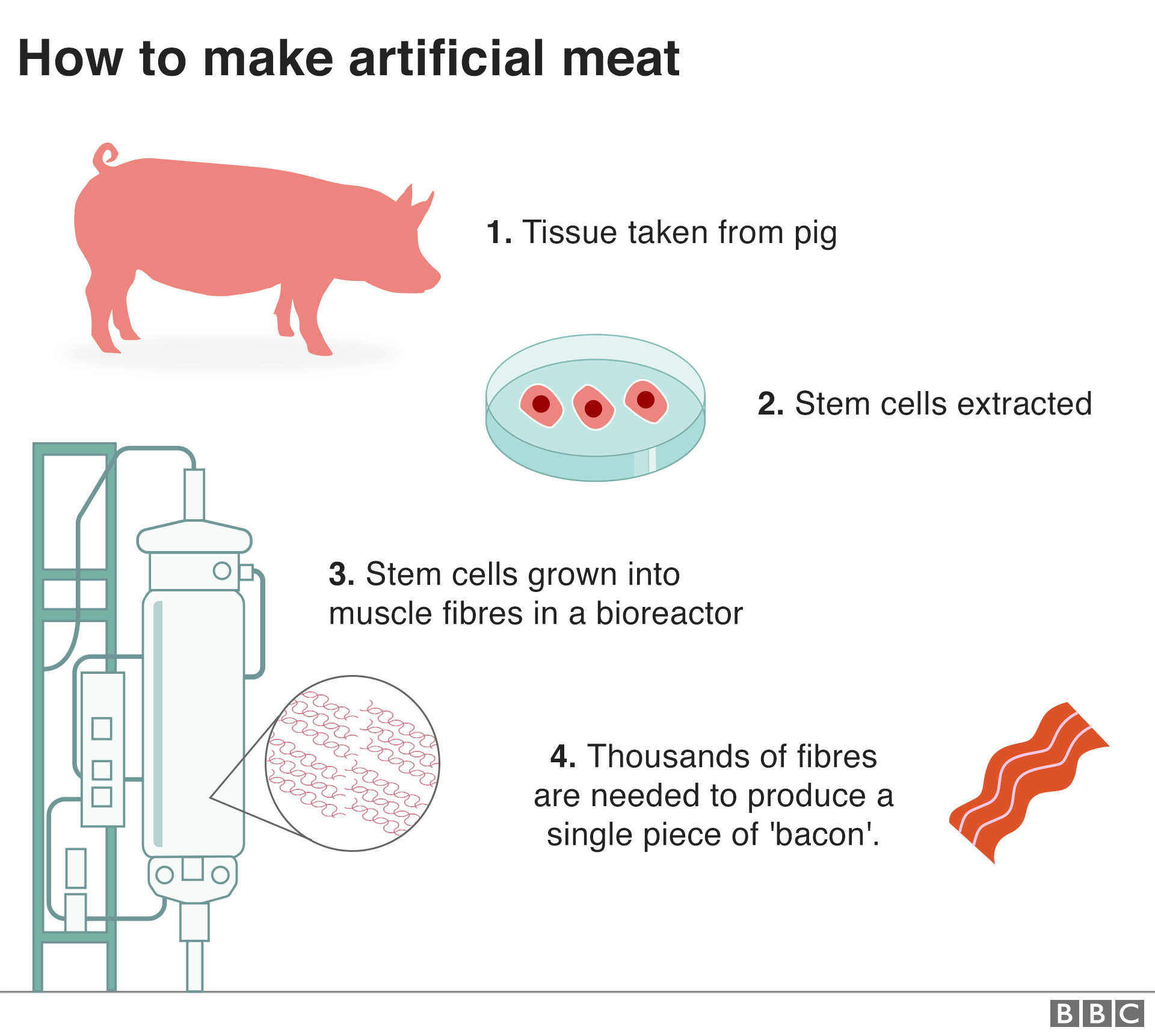

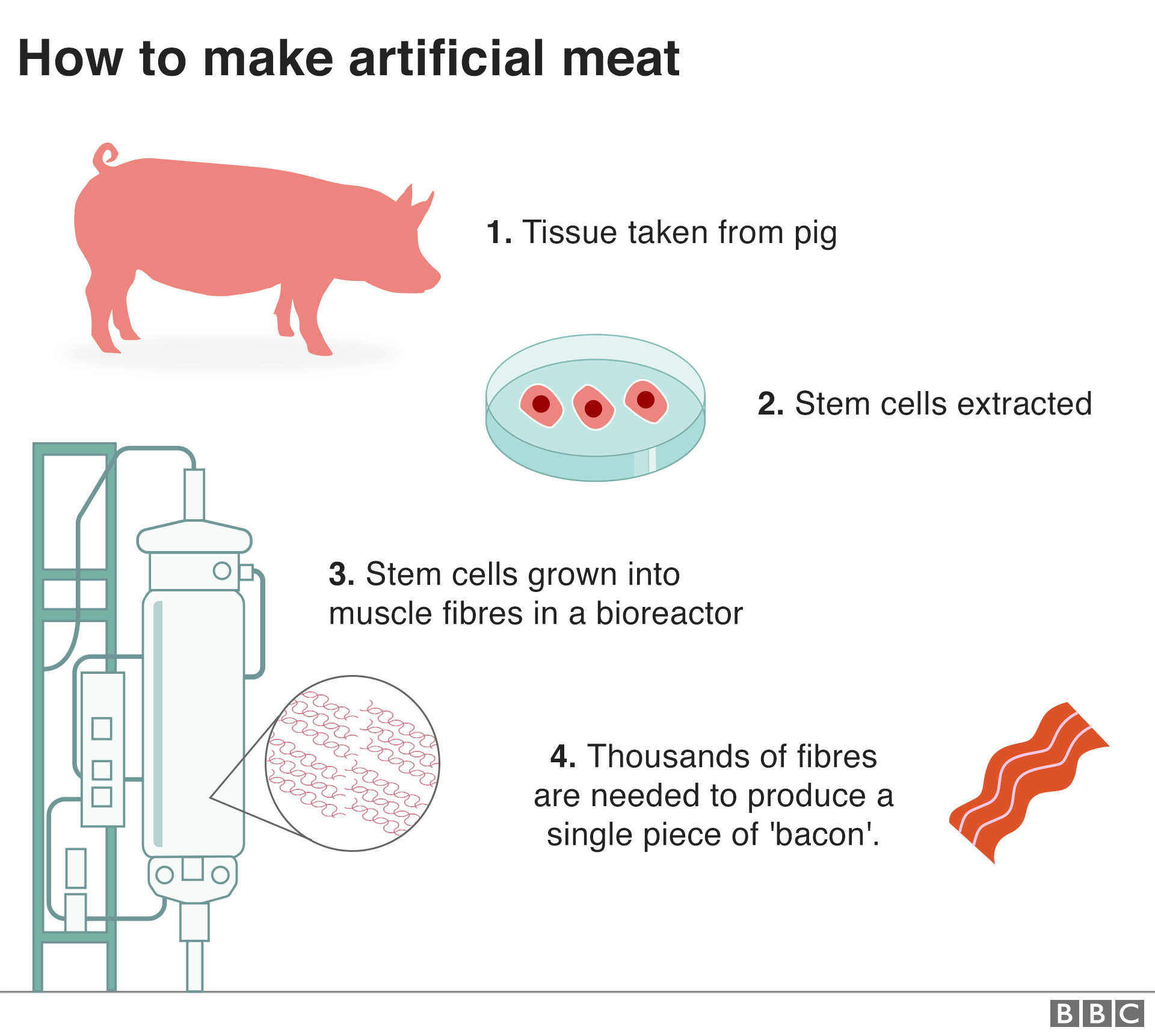

The second type of meat alternative is known as cultured or clean meat, which is produced using animal stem cells.

These cells are grown in a lab or bioreactor, usually with the help of a growth-enhancing substance taken from a calf foetus.

The process is arguably closer to a scientist growing replacement tissues and organs than the work of a cattle farmer.

Although not yet available in shops and restaurants, the techniques are being explored in a number of countries and could be on our plates in a matter of years.

A firm called Just hopes to have its lab-grown chicken on US shelves by the end of 2019.

There are high hopes that both the plant-based and lab-grown meats will appeal to hardened meat-eaters.

Image copyrightIMPOSSIBLE FOODSImage captionUS firm Impossible Foods has developed a plant version of heme - which gives beef its colour and taste

Image copyrightIMPOSSIBLE FOODSImage captionUS firm Impossible Foods has developed a plant version of heme - which gives beef its colour and taste

But getting these products on to our plates is not as straightforward as simply putting them into shops and restaurants.

Arguably, the biggest hurdle is getting permission to sell them.

Cultured meat firms must undergo a rigorous safety assessment.

In the EU, this process can take up to two years. If the European Food Safety Authority decides the product is safe to eat, a decision must be made about whether it can go to market - and how it should be labelled.

In the US, the timeframe is less certain and relies on approval from two separate departments: the Food and Drug Administration, which regulates the collection and culturing of animal cells, and the US Department of Agriculture, which decides how cultured meat can be marketed.

Media captionThese chicken nuggets were grown in a lab from cells taken from a living animal

Even with approval from regulators, there is still the need to win over the public.

For many consumers, the so-called "yuck" factor of lab-grown meat could be too strong for it to be considered an alternative to real meat - or something they even want to eat.

For others, the most important thing may be clear and transparent information on what they are eating and from where it has come.

In the US, there are demands for a more precise definition of "meat" before this new technology hits the shelves.

The term should only be used to describe "the tissue or flesh of animals that have been harvested in the traditional manner", the US Cattlemen's Association argues.

For producers of meat alternatives, the outcome of these debates could make or break their businesses.

It is thought that consumers are more likely to buy meat described as "clean" or "slaughter-free" than "lab-grown".

By Laura WellesleyChatham House

- 10 May 2019

- Share this with Facebook

- Share this with Messenger

- Share this with Twitter

- Share this with Email

- Share

Meat-free foods that "bleed" like the real thing are becoming increasingly common. Could these vegetarian alternatives replace "traditional" burgers and sausages?

Concerns about the environmental and health impact of our diets has seen interest in vegetarian and vegan foods grow.

This has boosted everything from flexitarianism to vegan sausage rolls and campaigns like "Veganuary".

While Quorn and Linda McCartney once ruled the meat substitute aisles of our supermarkets, new companies are appearing with a radically different vision of "meat-free".

Vegetarian "meat" designed to mimic the look, smell and taste of the real thing are already available, while scientists are developing lab-grown meats

ADVERTISEMENT

But with the arrival of these new dishes comes an increasingly animated debate about what can be called "meat", as well as how - and even if - it should be sold.

The first type of these new meat alternatives are plant-based products.

These are already available in restaurants, pubs and supermarkets, contributing to a growing market worth an estimated £4.6bn. Last week, the value of US firm Beyond Meat rose to nearly $3.8bn (£2.9bn) after its Wall Street debut.

The aim of plant-based "meat" is for it to be so similar to cook and eat as the real thing, that it is virtually indistinguishable.

It is made from plant proteins - usually wheat, pea or potato. Natural colourings like beetroot juice usually provide the "blood".

Another US firm, Impossible Foods, has developed a plant version of heme - which gives beef its colour and taste.

The second type of meat alternative is known as cultured or clean meat, which is produced using animal stem cells.

These cells are grown in a lab or bioreactor, usually with the help of a growth-enhancing substance taken from a calf foetus.

The process is arguably closer to a scientist growing replacement tissues and organs than the work of a cattle farmer.

Although not yet available in shops and restaurants, the techniques are being explored in a number of countries and could be on our plates in a matter of years.

A firm called Just hopes to have its lab-grown chicken on US shelves by the end of 2019.

- Cultured lab meat may make climate change worse

- Where should shops stock veggie burgers?

- US vegan food-maker Beyond Meat eyes $1bn valuation

- The veggie burger that bleeds when you cut it

There are high hopes that both the plant-based and lab-grown meats will appeal to hardened meat-eaters.

But getting these products on to our plates is not as straightforward as simply putting them into shops and restaurants.

Arguably, the biggest hurdle is getting permission to sell them.

Cultured meat firms must undergo a rigorous safety assessment.

In the EU, this process can take up to two years. If the European Food Safety Authority decides the product is safe to eat, a decision must be made about whether it can go to market - and how it should be labelled.

In the US, the timeframe is less certain and relies on approval from two separate departments: the Food and Drug Administration, which regulates the collection and culturing of animal cells, and the US Department of Agriculture, which decides how cultured meat can be marketed.

Media captionThese chicken nuggets were grown in a lab from cells taken from a living animal

Even with approval from regulators, there is still the need to win over the public.

For many consumers, the so-called "yuck" factor of lab-grown meat could be too strong for it to be considered an alternative to real meat - or something they even want to eat.

For others, the most important thing may be clear and transparent information on what they are eating and from where it has come.

In the US, there are demands for a more precise definition of "meat" before this new technology hits the shelves.

The term should only be used to describe "the tissue or flesh of animals that have been harvested in the traditional manner", the US Cattlemen's Association argues.

For producers of meat alternatives, the outcome of these debates could make or break their businesses.

It is thought that consumers are more likely to buy meat described as "clean" or "slaughter-free" than "lab-grown".