S'pore is known as a trustworthy place, so why are there so many scams?

It may be precisely because Singapore has a high-trust society that it attracts scammers

Jeremy Au Yong

Mobile Editor

In a way, spotting a scam is a bit like driving. Everyone overestimates their ability, and fatigue and stress make you worse at it. PHOTO: PEXELS

JAN 23, 2022

My friend - a highly educated digital native in her 30s - has the profile of someone most would expect not to be a victim of a scam.

And in fact, despite having lived in cities in Latin America and Africa that many Singaporeans would consider quite dangerous, she never even came close to getting scammed. Shot, yes, but never cheated.

Then she moved here.

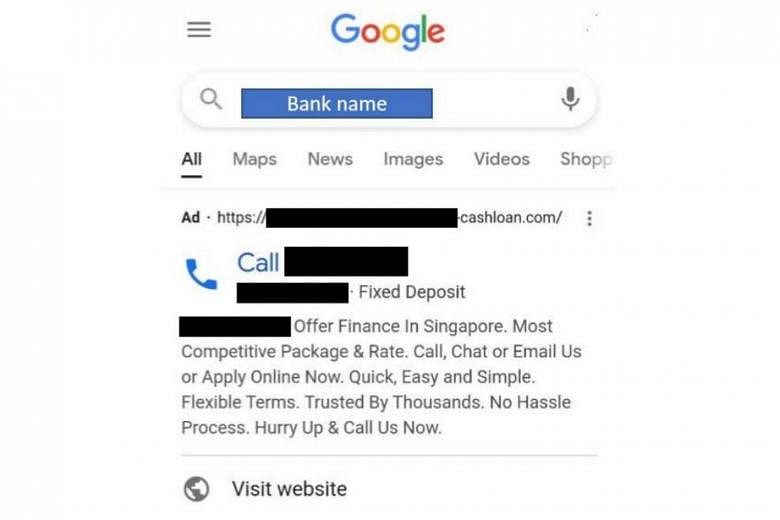

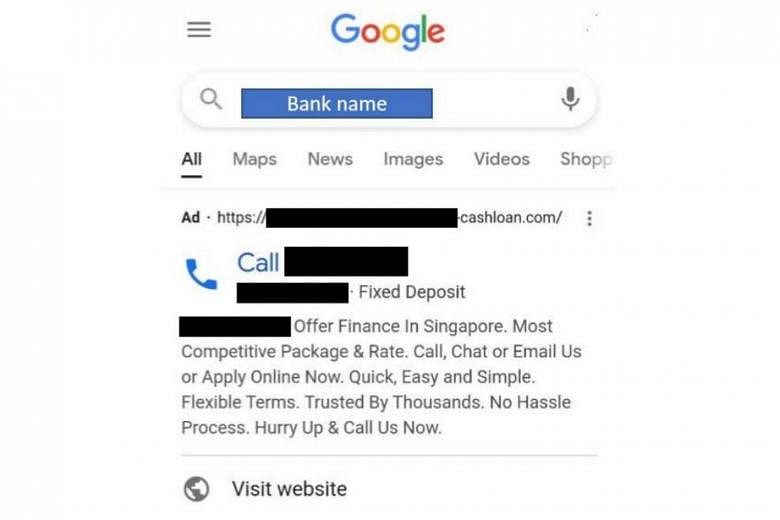

It began last year when she wanted to start a crowdfunding campaign to help a friend with medical bills. She searched for the popular fund-raising website gofundme.com on Google, clicked on the link that popped up, and set up her campaign.

She shared it with a group of her friends and within days had successfully raised a few thousand dollars. So far so good.

When the time came to close the campaign, she went to close the site and was puzzled when the site wouldn't let her log in.

She discovered to her horror that she never started a campaign on gofundme.com. In her haste to start the campaign, she had clicked on a link for a site that looked like it but had changed the name ever so slightly.

Further checking would reveal that Scamadviser, a scam-fighting website, rated that other crowdfunding site as "suspicious", and said the site's domain was registered with a company that has a high percentage of spammers and fraud sites. The site would also change its name a few months later.

(The silver lining is that this site did not disappear with all the money. It charged a fee nearly 10 times that of gofundme - but it could have been much worse.)

As you can imagine, there was some disbelief when she recounted this story. And victims of scams can tell you that compassionate understanding is not typically the general reaction to such tales.

How was it possible, people would ask, that she could have missed the incorrect name for so many days? And how did so many of her friends not point it out as well?

There are no good answers to questions like these. In hindsight, the ploy always seems so obvious.

ST ILLUSTRATION: CEL GULAPA

In a way, spotting a scam is a bit like driving. Everyone overestimates their ability, and fatigue and stress make you worse at it.

One thing I learnt from that episode is that everyone can be a victim, including those who believe they are immune.

But I also hypothesise that being in Singapore had made her more susceptible to falling for the ruse.

It's not that the incidence of cyber crime here is especially high when compared globally. It's just that being in Singapore may have meant she wasn't as vigilant as she should have been.

She got used to trusting people.

Powered by trust

It can be tempting to think that it really would be foolish for anyone to trust anyone else at this point of human civilisation.

After all, almost since money had value, humans have been trying to dishonestly liberate each other of it.

History is littered with all manner of audacious hustles, and each time, people have demonstrated no lack of willingness to trust each other again.

People have sold bridges that do not belong to them; promoted investments to fictional tropical islands; and even convinced others that they are princes from a country that has been a federal republic since the 1960s. And yet, every once in a while, you will find a similar scam working again.

MORE ON THIS TOPIC

4 common types of scams and how to recognise them

Is contactless payment safe? 5 tips to protect yourself in the wake of OCBC SMS scams

Ponzi schemes are a century old and one would argue society has really not developed any significant defences to it.

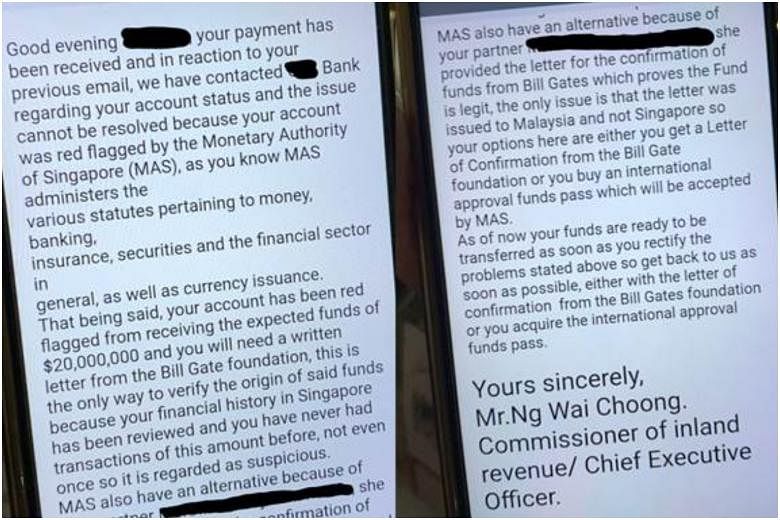

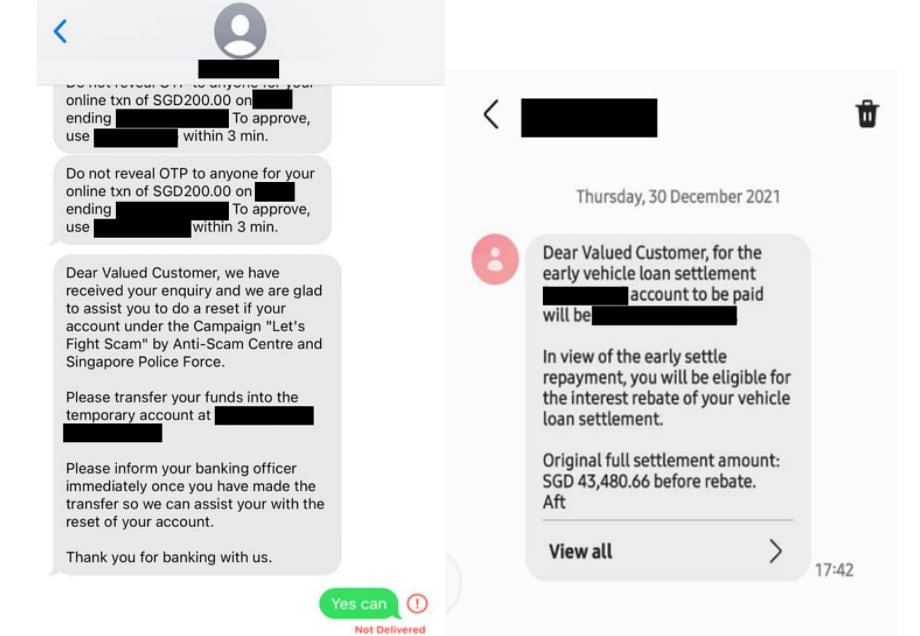

Most scams generally depend on some unchanging forces. Respect for authority, for instance.

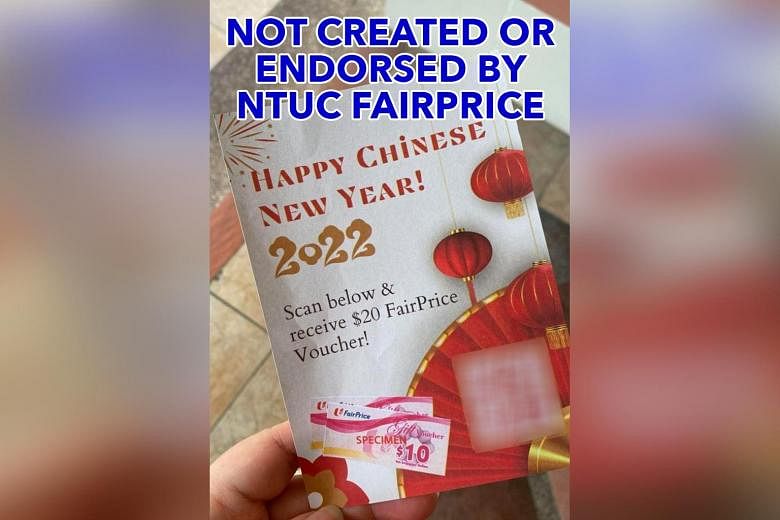

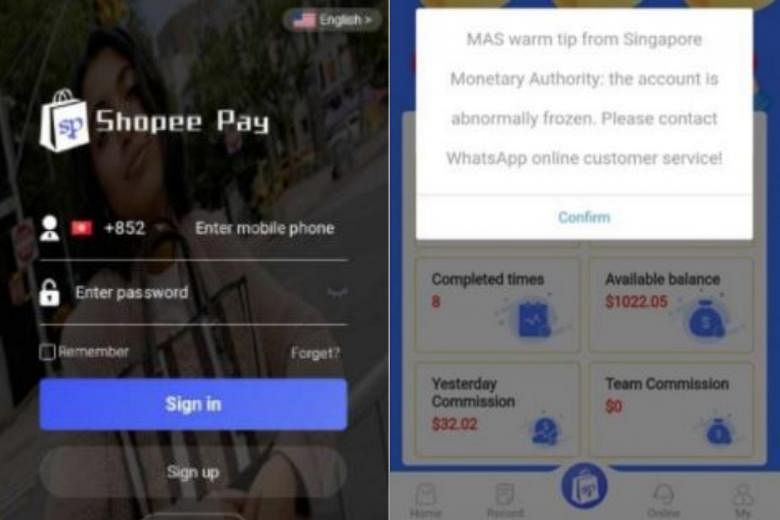

Nearly all your Internet scammers present themselves as some sort of authority figure.

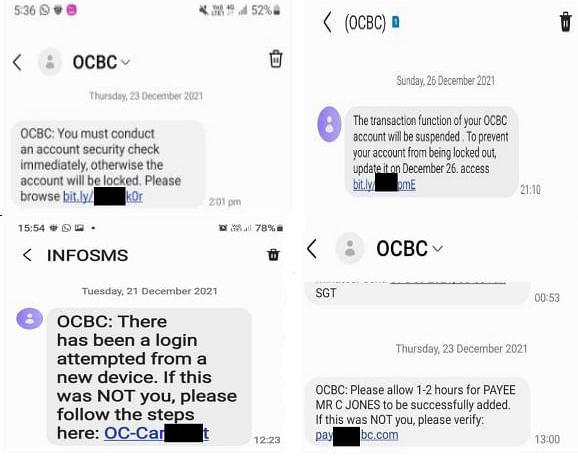

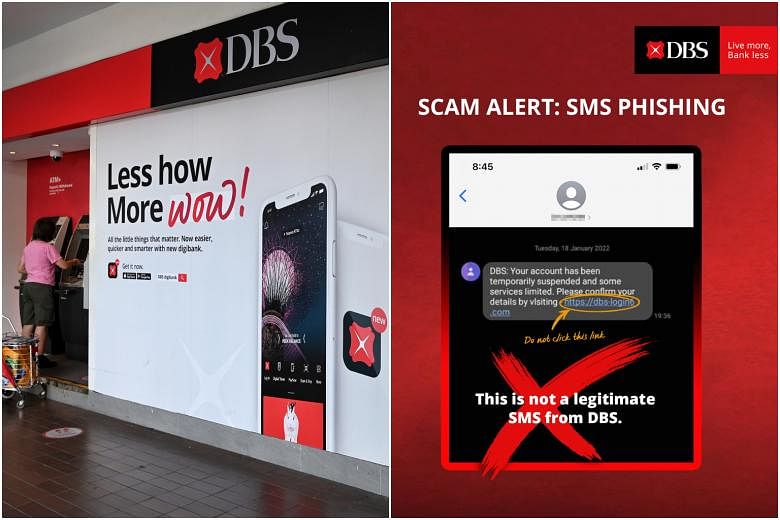

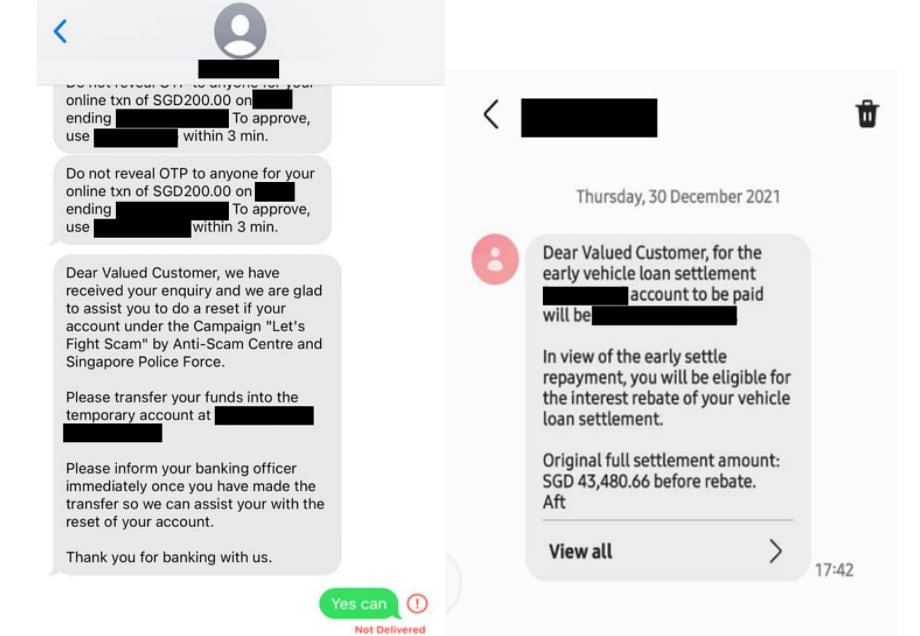

In the OCBC case,

they were masquerading as the bank. In others, they pretend to be the police, your telco or, in this time of pandemic, the Ministry of Health.

I get at least two calls a day from a recorded voice claiming to be from the health ministry, imploring me to press 3. I spend more time on the phone with the "press 3" woman than my own mother.

After establishing some sort of authority, the scammer's other move is to create a sense of urgency.

Maybe they tell you about a Covid-19 infection or a bunch of unpaid bills, maybe it's a pile of gold in some vault that is about to be confiscated - whatever it is, if you don't act soon, you're going to lose out on something good or have something bad happen to you.

The difference between your pre-Internet scams and your more modern ones is the scale. While in the past, scammers could seriously cultivate one target at a time, these days, scammers can hit millions of people at the click of a button.

That means the swindle can be a bit cruder. It doesn't matter if nearly everyone rejects it. All they really need is a small number of gullible people to bite.

And as the notorious showman and grifter P.T. Barnum famously said: "There's a sucker born every minute."

For the record, it is likely he never said this. Some people claimed he did and a bunch of people did not bother to verify it.

And that brings us back to trust, which is really what underpins all these scams through the years. Though methods and the ruses have changed, trust hasn't changed much at all.

As author Amy Reading noted, the capacity for gullibility "is unchanging over time because it is a function of how we are programmed, by biology and culture, to take in the external world. Any of our tools of empiricism, which generally hold us in pretty good stead, can also be used against us".

She was talking about Americans, but that also starts to explain why Singapore, despite being a high-trust society, can't seem to rid itself of the scam problem.

The Canadian paradox

Former Bank of England regulatory economist Dan Davies argues that it is precisely the high-trust societies that tend to become the hot spots for fraud.

In his book about financial crimes, Lying For Money, he calls it the "Canadian paradox".

He writes: "Why is it that the Canadian financial sector is so fraud-ridden that Joe Queenan, writing in Forbes magazine in 1985, nicknamed Vancouver the 'Scam Capital of the World', while shipowners in Greece will regularly do multimillion-dollar deals on a handshake?

"It is much more difficult to be a fraudster in a society in which people do business only with relatives or where commerce is based on family networks going back for centuries. It is much easier to carry out a securities fraud in a market where dishonesty is the rare exception rather than the everyday rule."

Intuitively, the Canadian paradox could just as well be a Singaporean one. People who normally trust that laws are upheld, that institutions are upstanding and that people they meet every day are generally honest, might not second-guess intentions as much.

It is, after all, impossible to verify everything, so every society decides how it balances what to check and what to take at face value.

In high-trust societies, that balance tips more towards trust.

Is the answer then to tip the balance the other way? Should people stop being so trusting here and should companies build in more levels of checks and verification?

Well, this is where it starts to get a little complicated.

Certainly we want to take all possible steps to make the lives of scammers as difficult as possible.

But we also have to be aware that we will likely never be able to plug every single loophole that we manage to squeeze out every scam.

Nor would we actually want to.

Scammers rely on some degree of trust to operate, but so does the legitimate non-scammer economy.

A society in which people do not trust each other is not just one where scammers fail to thrive, it is one where society and the economy cannot thrive. If every deal is high risk and it is best to just do handshake deals with close friends and family, there is just going to be fewer deals done.

Put another way, trust may create opportunities for scammers to steal wealth, but without it, there might not be any wealth to steal.

As Mr Davies notes, though fraud is expensive, there is a cost to trying to prevent it.

"The cost of dishonesty itself is inseparable from the extent to which bad actors drive out good. The trade-off that we need to make at the level of society is between these two quantities."

So where does that leave us?

Setting up safeguards and educating the public are important and are efforts that need to continue.

But it may well be that as long as we still tend to trust each other - and it will be a sad day if a time comes when this is no longer true - scams will never really go away.