Primary 1 registration: Where alumni privilege and distance rules can accelerate inequality

ACS Primary’s move bucks this trend and provides an opportune moment to relook P1 registration criteria

Cameron Kheng, Vincent Chua and Eik Swee

The Primary 1 registration exercise is currently driven by mechanisms that potentially reinforce pre-existing inequalities in society. PHOTO: ST FILE

UPDATED

APR 26, 2023

In the fairest possible world where allocations are based purely on chance, students would be assigned to their primary schools through a random process of balloting.

Whether “elite” or “neighbourhood”, all primary schools would comprise first-year students from across the social spectrum, rich or poor, near or far, and regardless of race.

In such a scenario, the correlation between social class background and the status of a school would trend towards zero.

However, this is far from the current reality. The distribution of students across Singapore’s primary schools is characterised by the rules of a game that run counter to the desire for a level playing field.

While this may have never been its intention, the Primary 1 registration exercise is currently driven by mechanisms that potentially reinforce pre-existing inequalities in society.

The Primary 1 registration exercise is

marked by several phases. Phase 1 is reserved for students whose siblings are currently studying in the school.

Phase 2A prioritises children whose parents and siblings are former students of the school, as well as parents who are members of its alumni association, staff of the primary school or members of its advisory and management committees.

Phase 2A also grants entry to children who had attended the Ministry of Education (MOE) Kindergarten tied to the desired school.

Phase 2B reserves placement for parents who volunteer with the school, are active community leaders, or members of school-affiliated organisations.

Finally, Phases 2C and 3 are open to all other applicants.

When a school is oversubscribed during a phase, especially during Phases 2B and 2C, distance rules will apply. This means that students who live within a 1km radius of the school are given priority ahead of those who reside farther away.

Competing interests

Debates over the Primary 1 registration exercise are tricky to navigate, often rife with competing interests from across the social spectrum.

For example, while many alumni claim that the current system helps them build on and preserve school ties, culture and heritage, others feel that these schools have essentially become exclusive clubs for the elite.

Discussions like these mainly coalesce around three critical features of the admissions process.

First, Phase 2A grants preferential choice to alumni parents, meaning that their children can gain entry into their former primary schools on the basis of their parentage without even needing to sit for anything resembling a test.

This essentially allows the past to be superimposed onto the present by sending parental privileges forward in time, intergenerationally, to children who did nothing in particular to merit them.

These children can then enjoy the material and reputational benefits of attending an elite school.

Whether this translates into actual gains at the Primary School Leaving Examination is another question, but perceptions of prestige can lead to self-fulfilling outcomes.

Second, schools grant preferential entry to parents who had volunteered at least 40 hours of service in their desired primary schools during Phase 2B of the exercise.

Were it the case that all parents had an equal capacity – in time, resources, or expertise – to render such services, this phase would hardly be contentious.

However, such capacities are heavily dependent on one’s socio-economic standing, especially when comparing the greater time flexibility that white-collar professionals have over lower-wage workers.

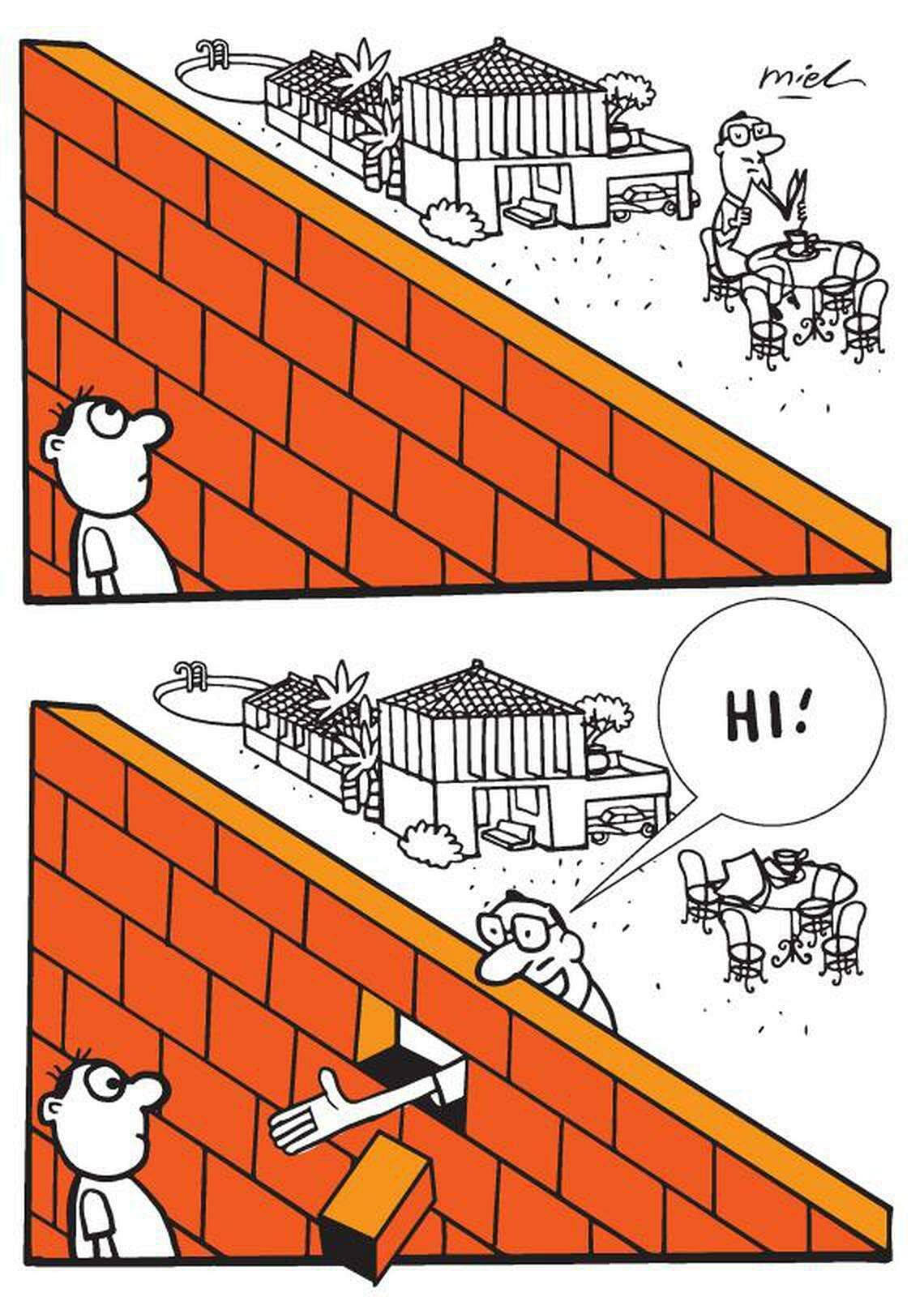

Third, when school places are oversubscribed, they are balloted on the basis of an applicant’s residential proximity to the primary school.

Again, this would hardly be contentious if the nation’s most popular schools were equally spread across the country, since this would grant families living in less wealthy neighbourhoods access to top institutions. However, this is not the case.

Many elite schools in Singapore are clustered within its wealthiest neighbourhoods, benefitting those already privileged to have a house there.

Catchment area inequalities

This final point on distance-based admission has drawn the most controversy among Singaporeans, and understandably so, since it lies at the intersection of various socially charged issues: the value of homes, the location of school and the factors contributing to social inequality.

There is nothing inherently wrong with distance-based criteria for primary school admissions.

In fact, holding all else equal, it makes perfect sense for parents to send their young children to the school nearest to their home.

As Education Minister Chan Chun Sing remarked in a 2022 parliamentary speech, it is “convenien(t) for a child to study in a nearby school as it reduces travelling time, allowing the child and family to spend more time, more meaningfully”.

Yet two uncomfortable truths persist.

First, schools are not perceived as equal across the board. Each year, the same crop of schools receive significantly more applicants than they can take in, indicating that parents clearly perceive stark differences in school quality.

Second, these very same schools are not evenly spread across the country and thus are not within reach of every Singaporean.

Instead, they are intensely clustered in and around the nation’s wealthiest neighbourhoods. Bukit Timah is a prime example, housing well-known schools such as Raffles Girls’ Primary School, Methodist Girls’ School and Nanyang Primary School.

Notably in 2022, in Phases 2A and 2B combined, Methodist Girls’ School received 168 applications for its 89 available places, and Nanyang Primary School received 222 applications for its 176 available places.

The application rates for these two schools were substantially higher than the national average of around one applicant for every two available places.

Taking these facts together, distance-based admissions can no longer claim to be a neutral tool of convenience but, when wielded by the wealthy, become an instrument by which elite boundaries are maintained.

In this way, the Primary 1 registration exercise can inadvertently become a mechanism of socio-economic division, contradicting the open and meritocratic principles upon which it seeks to stand.

These arguments are not mere conjectures, but have been verified by the work of academics.

In 2016, a study conducted by National University of Singapore economist Sumit Agarwal and his colleagues found that real estate prices responded fairly consistently to announcements of school relocations by MOE over a 10-year period from 1999 to 2009.

Lured by the prospects of distance-based entry, parents will go to great lengths – quite literally – to secure for their children a spot in an elite school.

Professor Agarwal and his colleagues’ findings still ring true today.

Following the recent announcement that Anglo-Chinese School (Primary) would move from its Barker Road location to the young town of Tengah, real estate analysts quickly predicted corresponding movements in the housing market for the two localities.

Whether these play out in reality remains to be seen.

In two of our own recent projects, we studied 40 years of school enrolment data stretching back to 1971, analysing school compositions at the primary, secondary and junior college levels, spread across neighbourhoods of different socio-economic characteristics.

Our analysis showed that the concentration of elite schools (primary, secondary and junior college) within wealthy neighbourhoods like Bukit Timah has led to patterns of social segregation along gendered and racial lines over time.

This suggests strongly that elite school statuses have combined with neighbourhood wealth to reinforce patterns of social closure and exclusivity.

Distance-based admissions are not inherently pernicious to social equality. By themselves, they do not foster the kinds of inequality that the state or its concerned public are anxious to solve.

It is only in combination with pre-existing inequalities, namely in neighbourhood wealth and elite school locations, that distance-based admissions become an instrument of socio-economic division.

Good primary schools should ideally be within reach of all students regardless of where they live, but they instead are concentrated within wealthy areas, thus turning distance-based enrolment into a tool of social reproduction.

Nevertheless, one such school has bucked the trend.

From Barker Road to Tengah

Anglo-Chinese School (Primary) will be moving from its current Barker Road campus in Newton to Tengah in 2030. ST PHOTO: RYAN CHIONG

We affirm the progressive spirit behind

ACS Primary’s planned relocation from Barker Road to Tengah, as well as the opening of its enrolment to girls and special needs students.

This countercultural decision holds the potential to equalise opportunities in at least two ways.

First, young families residing in Tengah, who may not otherwise have had the opportunity to send their children to an elite school in Bukit Timah, can now do so in 2030 when ACS Primary relocates.

Second, the move will likely diversify the demographic mix of its classrooms, thereby promoting greater social mixing among students from different socio-economic and now gendered backgrounds too, given the shift from an all-boys to a co-ed school.

The status quo could have been easily preserved had the MOE and ACS leaders chosen not to pursue this relocation. But they did, causing quite a stir.

Ultimately, the move is a social experiment with inherent challenges and risks, as evident from the concerns expressed among some alumni in recent months.

That it has gone ahead in spite of these concerns demonstrates courage and a promising commitment to equality.

Positive steps towards meritocracy

The irony of the Primary 1 registration exercise will not be lost on astute observers given the fact that its first few phases rely on network mechanisms that reduce, rather than promote, social mixing.

This would seem both jarring and contradictory to the ideals of meritocracy which in Singapore we have infused into our daily sensibilities.

Regardless, the ACS Primary example illustrates one important principle – social networks can be re-imagined as forms of social mixing, thus promoting the sharing of resources across groups, rather than the reversion to tribalistic forms of social segregation. Instead of tightening its elite circles, ACS Primary’s move to Tengah loosens them.

In his parliamentary speech in April, Mr Chan called attention to the power of social mixing to mitigate inequalities, urging Singaporeans from elite schools to share their networks and opportunities not just with students of their alma mater but with those in other schools as well.

Indeed, considerable research has affirmed the power of cross-class interactions in building social equality.

Recent papers by Harvard economist Raj Chetty and his colleagues illustrate this, showing that social mobility among individuals of a low socio-economic status (SES) can be enhanced by deeper and more frequent connections with high-SES peers.

In the light of this, ACS Primary’s move to Tengah exemplifies one indirect yet potent fix to the Primary 1 registration exercise.

There are times when the pursuit of social equality demands more than just a nominal balancing of differing opinions.

Given that public dialogue over educational elitism and school location has fruitfully intensified over the recent months, it is an opportune moment now to take more seriously the goal of tackling educational inequality, starting first with the Primary 1 registration exercise, but hopefully continuing forward into every corner of the educational system.

- Cameron Kheng is a research scholar reading his master’s in the Department of Sociology at Nanyang Technological University.

- Vincent Chua is associate professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at National University of Singapore.

- Eik Swee is senior lecturer in the Department of Economics at University of Melbourne.