Lessons from the Adani debacle

There are many red flags that investors need to watch

Vikram Khanna

Associate Editor

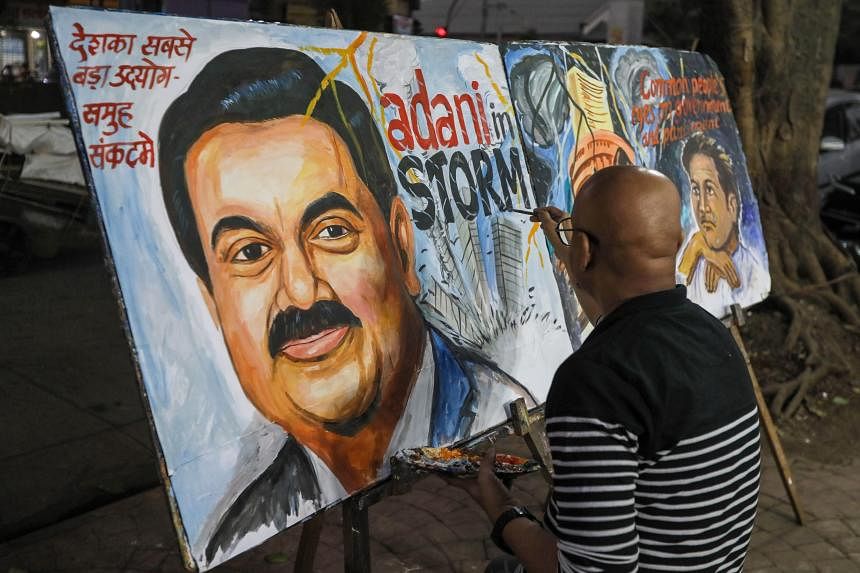

The main cause of the Adani empire crisis was a report by a New York-based activist short-seller called Hindenburg Research. PHOTO: EPA-EFE

Feb 7, 2023

Never before in corporate history has the net worth of a single individual fallen so much in one week. The chairman of India’s Adani Group,

Mr Gautam Adani, lost US$52 billion (S$68 billion) between Jan 25 and Feb 1. And the market capitalisation of his group – until recently India’s second-largest conglomerate and biggest builder of infrastructure – crashed by more than US$100 billion over the period, from around US$218 billion.

How this dramatic story will evolve is a matter for speculation, but meanwhile, there are lessons to be learnt for investors.

To recap recent events, the main cause of the crisis that so swiftly engulfed the Adani empire was a bombshell of a report by a little-known New York-based activist short-seller called Hindenburg Research.

Damning allegations

Accusing the Adani Group of pulling off “the largest con in corporate history”,

Hindenburg made some damning allegations in its 106-page forensic study of the group, which it claims took two years to complete.

It alleged that the group had engaged in “brazen stock manipulation and accounting fraud” over decades. Part of its modus operandi, according to Hindenburg, was to use an intricate web of offshore shell companies, based mainly in Mauritius and controlled by the brother of the group’s chairman and close associates, that funnelled billions of dollars into Adani companies in India, inflating their stock prices.

The price increases were indeed spectacular. For instance, over three years through 2022, Adani Total Gas soared by close to 2,000 per cent, the group’s flagship company Adani Enterprises rose over 1,700 per cent, and Adani Green Energy – a renewables company – was up more than 750 per cent.

At their peak, Adani companies’ price-to-earnings ratios were stratospheric – more than 1,000 for Adani Green Energy, over 800 for Adani Gas, and over 400 for Adani Enterprises, all multiple times industry averages. Hindenburg estimated that the group’s seven listed companies had a downside of 85 per cent, based on fundamentals.

Backed by a 413-page document, the Adani Group vigorously denied Hindenburg’s allegations, which it described as “maliciously mischievous” and “a reckless attempt by a foreign entity to mislead the investor community and the general public, undermine the goodwill and reputation of the Adani Group and its leaders, and sabotage the FPO (follow-on public offering) of Adani Enterprises”, which had been planned for the end of January.

Defending its corporate governance and business practices, it said the Hindenburg report was “a calculated attack on India, the independence, integrity and quality of Indian institutions, and the growth story and ambition of India”.

In a sharply worded rejoinder, Hindenburg Research claimed that the Adani Group had ignored or side-stepped its key allegations and that its response was “obfuscated by nationalism”.

It said the group had “attempted to conflate its meteoric rise and the wealth of its chairman, Gautam Adani, with the success of India itself”. And while India was “an emerging superpower with an exciting future”, that future is being held back by the Adani group, “which has draped itself in the Indian flag while systematically looting the nation”.

Thumbs down from the market

The markets apparently did not buy the defence of the Adani Group, whose share prices continued to plummet through the last week of January. Nevertheless, Adani Enterprises’ FPO went ahead and was even oversubscribed, thanks mainly to funding by some Indian tycoons, an Abu Dhabi conglomerate and a London-based asset manager.

Notably, retail investors and mutual funds hardly participated. In fact, along with institutions, they were likely among the sellers, because by the time the FPO closed, the share price of Adani Enterprises had fallen about 30 per cent below the offer price. This forced the Adani Group to cancel the offer and refund investors.

In a video address, Mr Adani explained that given the volatility in the stock price, this was the “morally correct” thing to do. The company considered the interest of investors “paramount” and wanted to “insulate them from further financial losses”, he said.

He added that “our balance sheet is very healthy with strong cashflows and secure assets, and we have an impeccable track record of servicing our debt”. He also claimed that Adani Enterprises’ future plans would be unaffected, and its growth would be internally funded.

But this would be a departure from the group’s past practice, which was to fund growth largely through debt, which had reached around US$30 billion by the end of January.

One of its borrowing tactics was by pledging shares to banks. Although this worked well while share prices were soaring, it would be hard to pull off when they are falling. Future bond and equity issues would also be difficult, at least until investor confidence is restored, which, judging from continued declines in the group’s share prices, has yet to happen.

It is doubtful that internal accruals alone can fund the group’s ambitious expansion plans. Although it operates in many infrastructure-based industries with steady and predictable cash flows, it lacks a major “cash cow” comparable to, for instance, the Tata Group’s IT giant Tata Consultancy Services or the Reliance Group’s petrochemical operations.

It has started to pre-pay some of its loans, which would reduce its debt-servicing burden. It can also sell off some of its impressive collection of assets. But as a result, it would have fewer resources as well as assets to enable its expansion – which means its future growth is likely to be slower than in the past.

Lessons for investors

So what are the main lessons that can be drawn from the Adani Group’s debacle?

First, which should be obvious but was surprisingly ignored, is that companies’ share prices can be vulnerable when they rise exponentially, especially when the businesses in which they operate are, like in the case of the Adani Group, mainly traditional, with relatively low margins.

Second, even if allegations of fraud against a company are unproven – as is the case with those in the Hindenburg report – if they look damning and are even halfway credible, investors sell first and ask questions later, without even being deterred by the fact that, as a short-seller, Hindenburg had a vested interest in triggering declines in the share prices of Adani Group companies.

Third, investors should be cautious when investing in politically connected groups, even if this is only a perception. Although both the Adani Group and the government of India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi deny being connected, perceptions of their connectedness are widespread.

It is not lost on observers, for instance, that the group’s fortunes soared and Mr Adani’s net worth rose more than 14-fold, from about US$7 billion in 2014 – the year the Modi government came to office – to over US$100 billion by the end of 2022.

Perceptions of the political connectedness of companies, even if unproven, can unleash all manner of excesses, such as state-owned banks lending to these companies more freely than to others, money being poured into their stocks regardless of valuations, and regulators treating them with kid gloves. Such developments should be red flags.

The fact that the majority of the domestic lenders to the Adani Group were state-owned banks and that most private banks – which are less subject to political influence – have avoided exposure to the group is also notable.

Another red flag should appear when analyst coverage of a company or group is unusually thin. As at early January, most Adani Group companies had only one or two analysts covering them, whereas coverage of companies in the same industries as well as other large Indian companies was widespread. The disparity is curious, given the high-profile activities of the Adani Group and its size.

A similar concern should arise when retail investors and mutual funds avoid certain companies, as was the case with most of the Adani companies, which are not widely held by Indian mutual funds. The fact that these funds, together with retail investors, hardly participated in Adani Enterprises’ FPO was another sign of weak market confidence.

Fifth, while domestic scrutiny of companies can be cut short, suppressed or prevented through legal actions – and the Adani Group has succeeded in quashing many investigations into its practices by the Indian media – once global investors get involved, there is more external scrutiny of companies, which can be intense, fearless and harder to contain.

Finally, invoking nationalism – claiming, for instance, that the country is under attack – as a defence against a short-seller doesn’t work. It might score political points at home, but as the Adani Group’s sell-off testifies, it does not impress investors.

Despite its devastating setback, the Adani Group, which controls vast infrastructural assets and has a good record of project execution, is likely to remain a significant player in India, even if it grows more slowly.

Its fall from grace is unlikely to have a major impact on India’s growth story or macroeconomy, or even on its banking system; local banks’ exposure to the group, which is concentrated mainly in state-owned banks, is reckoned to be only around US$10 billion. The lenders’ claims that their loans are well collateralised are credible, given the Adani Group’s solid assets and the fact that most of their loans were made several years ago.

The biggest losers are likely to be international banks and bondholders, which account for most of the group’s debts and did their lending more recently and at higher valuations.

As to how India’s stock markets will be affected, although the Hindenburg report targeted a single group and the rest of India’s market was little affected, it did raise issues that will make investors more vigilant towards some of the corporate governance practices that prevail in India as well as the conduct of market regulators, which at least in the case of the Adani Group is widely regarded as falling short of best practices.

Restoring investor confidence in the Adani Group is achievable. But much will depend on actions by India’s market regulators pertaining to the group, which would need to be made public and be credible to investors and after that, what actions, if any, the group takes to change its business practices.

For both regulators and the group, maintaining the status quo is not an option.