- Joined

- Jul 10, 2008

- Messages

- 64,866

- Points

- 113

Webb Telescope Finds Evidence of Massive Galaxies That Defy Theories of the Early Universe

The six “universe breakers” appear much larger than what scientists thought was possible at that time

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Teresa_Nowakowski.png)

Teresa Nowakowski

Daily Correspondent

February 24, 2023

:focal(350x237:351x238)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/44/b0/44b00258-cc50-4e51-b5d0-c1337b736a46/low-res_massive1png.png)

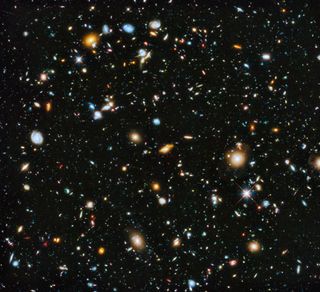

Images of the six objects thought to be massive galaxies from the early universe NASA, ESA, CSA, I. Labbe (Swinburne University of Technology). Image processing: G. Brammer (Niels Bohr Institute’s Cosmic Dawn Center at the University of Copenhagen)

Astronomers have identified what appear to be six massive galaxies from the infancy of the universe. The objects are so massive, that if confirmed, they could change how we think of the origins of galaxies.

The findings, published Wednesday in Nature, use data from the James Webb Space Telescope’s infrared-sensing instruments to picture what the universe looked like 13.5 billion years ago—a time when it was just 3 percent of its current age.

Just 500 to 700 million years after the big bang, the potential galaxies were somehow as mature as our 13-billion-year-old Milky Way galaxy is now.

The mass of stars within each of these objects totals to several billion times larger than that of our sun, according to the research. One of them in particular might be as much as 100 billion times our sun’s mass. For comparison, the Milky Way contains a mass of stars equivalent to roughly 60 billion suns.

“You shouldn’t have had time to make things that have as many stars as the Milky Way that fast,” says Erica Nelson, an astrophysicist at the University of Colorado Boulder and a co-author of the study to Lisa Grossman of Science News. “It’s just crazy that these things seem to exist.”

Researchers expected to find only very small, young galaxies this early in the universe’s existence. How these “monsters” were able to “fast-track to maturity” is unknown, says Ivo Labbé, an astrophysicist at Swinburne University of Technology in Australia and the study’s lead researcher, in an email to Marcia Dunn of the Associated Press.

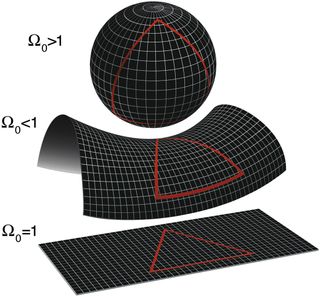

According to most theories of cosmology, galaxies formed from small clouds of stars and dust that gradually increased in size. In the early universe, the story goes, matter came together slowly. But that doesn’t account for the massive size of the newly identified objects.

“The revelation that massive galaxy formation began extremely early in the history of the universe upends what many of us had thought was settled science,” says Joel Leja, an astronomer and astrophysicist at Penn State and a co-author of the study, in a statement. “We’ve been informally calling these objects ‘universe breakers’—and they have been living up to their name so far.”

Emma Chapman, an astrophysicist at the University of Nottingham in England who was not involved in the research, tells the Guardian’s Hannah Devlin that these findings, if confirmed, could change how we conceive of the early universe. “The discovery of such massive galaxies so soon after the big bang suggests that the dark ages may not have been so dark after all, and that the universe may have been awash with star formation far earlier than we thought,” she tells the publication.

Still, it might not be time to rewrite cosmology just yet: The researchers say it’s possible some of the objects could be obscured supermassive black holes, and that what appears to be starlight in the images could actually be gas and dust getting pulled in by their gravity.

“The formation and growth of black holes at these early times is really not well understood,” Emma Curtis-Lake, an astronomer at the University of Hertfordshire in England who was not part of the study, explains to Science News. “There’s not a tension with cosmology there, just new physics to be understood of how they can form and grow, and we just never had the data before.”

To verify their findings, the researchers could take a spectrum image of the objects they’ve pinpointed. This would help reveal how old they are. Galaxies from the early universe appear to us as very “redshifted”—meaning the light they emitted has been stretched out on its long journey to Earth. The higher the redshift value, the more the light has been stretched and the more distant and aged the galaxy is. With spectroscopy, scientists could determine whether their potential galaxies, or “high-redshift candidates,” are as old as they appear, or if they are just “intrinsically reddened galaxies” from a more recent time, says Ethan Siegel, a theoretical astrophysicist who was not involved in the study, to CNET’s Eric Mack.

While Leja agrees that more observations are needed to confirm the findings, he notes in the statement, “Regardless, the amount of mass we discovered means that the known mass in stars at this period of our universe is up to 100 times greater than we had previously thought. Even if we cut the sample in half, this is still an astounding change.”