Rubbish survey.

The food stalls may not have raised prices but they cut down on the portion sizes and/or ingredients.

Study finds eating out cheapest in Toa Payoh, most expensive in Bishan; many food stalls didn't raise prices following GST hike

TODAY file photoAn Institute of Policy Studies report found that on average, a person in Singapore spends S$16.89 if he eats all three meals at hawker centres, food courts and kopitiams.

Follow us on

Instagram and

Tiktok, and join our

Telegram channel for the latest updates.

- Researchers from the Institute of Policy Studies visited 829 eateries across Singapore to gather prices of food and drinks in late 2022

- When they revisited some of them again in early 2023, they found that many of them had not raised prices

- Stall owners spoke of hardships of having to manage rising operation costs and not raising prices by too much for fear of driving away customers

- On average, a person spends S$16.89 if he eats all three meals at hawker centres, food courts and kopitiams

- Toa Payoh reported the lowest cost of S$15.98 for each person, while Bishan featured the highest average three-meal cost of S$18

BY

Published March 13, 2023

SINGAPORE — Despite the rising costs of operating a food stall in hawker centres, food courts and kopitiams, many stall owners did not raise prices between late last year and early this year, a study has found.

Of those who did, the majority increased prices only by a small margin — not exceeding 30 cents for each food item they sold — for fear of driving away their customers. And for most food items surveyed, price increases did not exceed 10 cents on average.

The study by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS), released on Monday (March 13), also found that the iced Milo chocolate drink had the highest relative increase in prices, going up by 12 cents, or 7 per cent on average. A total of 23 out of 55 stalls surveyed raised their prices of the drink, whereas the rest did not.

Sliced fish soup with rice went up by 28 cents, or about 5 per cent, and fishball noodles rose by 19 cents, which is also about 5 per cent.

Seven out of 19 sliced fish soup sellers surveyed raised prices for the dish, and 11 out of 30 fishball noodle sellers did the same.

The study was done by recording food and drink prices from 829 food establishments between September and November 2022.

After the

increase in the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in Jan 1 this year, researchers revisited 50 establishments, comprising a total of 263 stalls, in January and February to record any price changes.

The researchers said that the study served to “examine the effects, if any, of the increase of the GST on food prices”.

The study, titled The Cost of Eating Out: Findings from the Makan Index 2.0, was conducted by IPS researchers Teo Kay Key, Hanniel Lim and Mindy Chong.

They said that the survey was done as a way to better understand the costs of living in Singapore and does not provide any value judgement on the pricing strategy of food establishments.

As food and drink prices were collected mainly through menus at stalls, the researchers said that some prices might be understated especially if menu prices were not updated regularly.

Another note was that the smaller number of establishments revisited was partly because many had later closed down or changed hands, they added.

WHY IT MATTERS

The rising cost of living has been closely watched, with Singapore’s core inflation rate

rising by 5.5 per cent in January, the fastest pace in more than 14 years.

GST was increased from 7 per cent to 8 per cent on Jan 1, affecting consumer spending.

The Household Expenditure Survey in 2017 and 2018 showed that around 7.4 per cent of a household’s spending went to the types of food that hawker centres, food courts and coffee shops serve. In comparison, only 6.4 per cent of expenses were spent on recreation and culture and 5.5 per cent of expenses were spent on health.

"Given the culture of eating out in Singapore, many Singaporeans are likely to head to one of these food establishments to have their meals if they decide not to prepare their own meal at home," the researchers stated in the executive summary of their report.

"Examining data on food prices in these locations thus allows us to examine trends on price variations based on different factors and derive the estimated eating-out budget of an average Singaporean, which will further (aid) understanding on one aspect of living costs in Singapore."

Infographic: Samuel Woo

WHAT THE STUDY FOUND

Researchers studied a variety of food and drink items commonly consumed during breakfast, lunch or dinner. They also took into account dietary restrictions when selecting which food items to consider.

A total of 18 items were included in the study, including kopi-o (black coffee), breakfast sets (kaya toast, two soft-boiled eggs and a coffee or tea), mee rebus, wanton noodles, economy rice (rice with two vegetables and one meat), and economy bee hoon sets (bee hoon with fried egg and chicken wing).

Researchers then collected drink and food prices from the menus of 829 food establishments, comprising 92 hawker centres, 101 food courts and 636 kopitiams within 26 residential neighbourhoods in Singapore.

Infographic: Samuel Woo

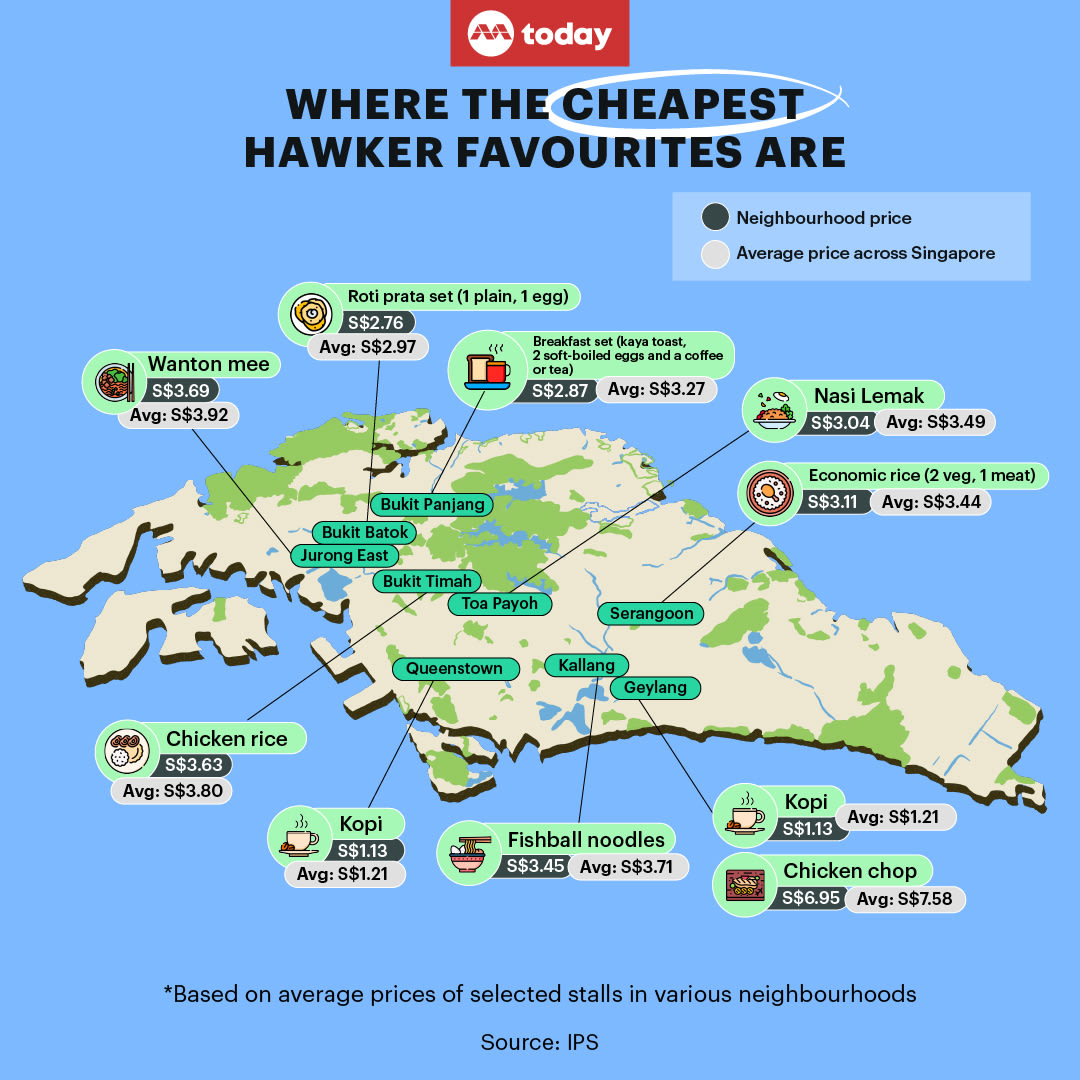

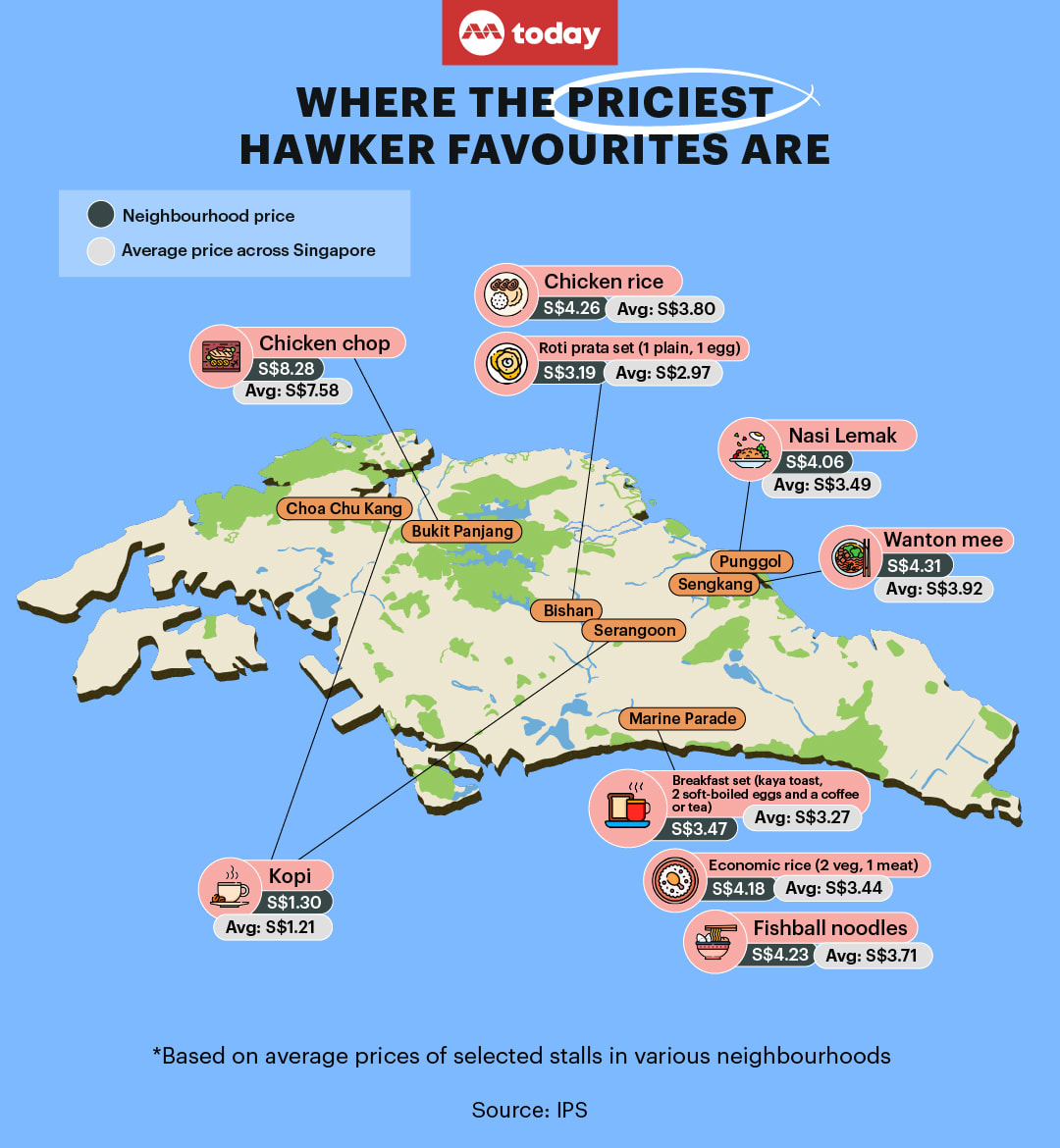

REGIONAL DIFFERENCES IN FOOD AND DRINK PRICES

Apart from price increases, researchers also found "regional differences" for nine out of 18 food and drinks selected for the study.

- All the drinks (kopi-o, kopi, iced Milo, iced lime juice, canned drink with ice) as well as chicken chop were cheapest in the central region of Singapore

- Breakfast sets and fishball noodles were cheapest in the north of Singapore

- Roti prata was cheapest in the western region

With some exceptions, food courts generally priced their offerings at higher prices, followed by kopitiams and then hawker centres. The food items that did not follow these trends were breakfast sets, chicken rice, economic rice and vegetarian bee hoon sets.

"These trends clearly indicate that while food establishments like hawker centres, food courts and kopitiams are viewed as more affordable options, there is still variation in the prices of food and drinks sold in these establishments, depending on the content," the researchers said.

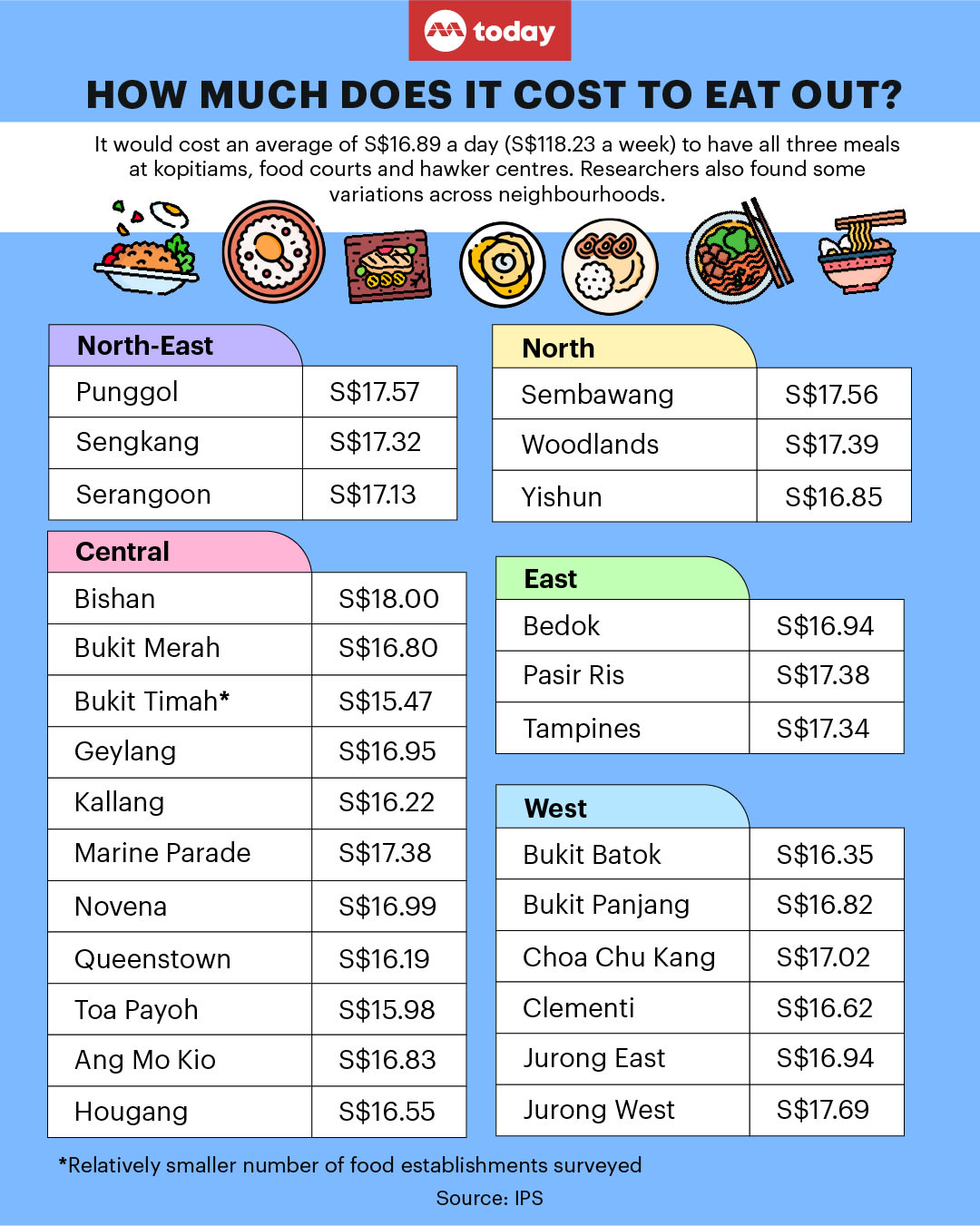

TOTAL MEAL COSTS

Across the neighbourhoods studied, researchers found that breakfast on average cost S$4.81, lunch S$6.01, dinner S$6.20. Each meal comprises a food and a drink, and the study derived these costs by aggregating the average of various food and drink combinations based on convention and the opening times of stalls.

On average, a person spends S$16.89 if he eats all three meals at hawker centres, food courts and kopitiams.

When comparing between neighbourhoods, researchers found that the differences in costs for lunches and dinners to be statistically significant.

Marine Parade had the highest average breakfast cost at S$5.12, Sembawang reported the highest average lunch cost at S$6.35 and Jurong East reported the highest average dinner cost at S$6.71.

In contrast, Queenstown reported the lowest average breakfast cost at S$4.33, Kallang reported the lowest average lunch cost at S$5.64 while Toa Payoh reported the lowest average dinner cost at S$5.89.

When adding up all three meals, Toa Payoh reported the lowest cost of S$15.98 for an individual, while Bishan featured the highest average meal cost of S$18.

Bukit Timah was excluded from these comparisons due to the small sample size — the neighbourhood only had three kopitiams and two hawker centres located within its boundaries.

Infographic: Samuel Woo

CHANGES IN FOOD PRICES

The researchers also revisited 50 food establishments to make comparisons of prices between late 2022 and early 2023.

They found that most stall owners in these establishments did not raise prices of food that they sold, and a majority of those increased their prices only by a small margin. The average increases in prices at these revisited stalls did not exceed 30 cents, and did not go above 10 cents for most food items.

Apart from the numbers, the researchers also struck up conversations with the stall owners who spoke of the "hardships of having to manage the rising cost of operation and not increasing prices by too much in order to not drive away customers".

"From various interactions with stall owners, researchers found that stall owners often sought to justify the prices of their food.

"They also emphasised their decision to not increase prices if they had not done so, and took pride in keeping their prices the same despite the inflationary pressures threatening many food stall owners’ income and job security," the report stated.

Giving an example, researchers said that a drink stall owner at a Tampines hawker centre who had not raised prices since 2020 later did so reluctantly in 2023, because he could not cope with the rising cost of ingredients such as eggs and evaporated milk at the prices for which he was selling his food. He was trying hard not to disappoint his loyal customers.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

Addressing the smaller number of eateries revisited, the researchers said that this was partly due to stalls undergoing changes, such as business closure or changes in ownership, during the period of data collection. The other reasons were due to time and manpower constraints.

"While the stalls we surveyed during the data collection process might have closed or changed hands for various reasons, news reports indicate that stall owners who had closed their stalls during this period cited rising operating prices for the closing of their stalls with both rental and ingredient prices increasing drastically over the past year," the researchers added.

It was still "evident" that most stall owners in the revisited food establishments did not increase the prices of the food items they sold, though the researchers cautioned against making sweeping conclusions from the analysis of the data.

Other limitations included:

- A primary dependence on menu prices, rather than the interviewing of stall owners due to time constraints and the reluctance of some owners to verbally disclose their prices. This may lead to the understating of prices, especially if menu prices were not regularly updated

- The prices of food items were taken at face value, which means that they have not been adjusted to reflect the differences in quantity and quality between various food items

In response to queries from TODAY about public reaction on whether other considerations were taken into account for the study, since food prices could have been raised significantly prior to the survey, the researchers said that their study only looked at increases following the GST hike and not increases owing to other factors such as the Covid-19 pandemic or the Russia-Ukraine war.

The researchers also noted that their study had specified that the quality and quantity of food were not accounted for, and that the difference in prices could have reflected variations in these aspects.

As to whether the study had accounted for price differences due to the type of food establishment, they said that they had used a standardised criteria to classify establishment types to reflect difference in food prices. For example, hawker centres were defined in the study as "open-air, standalone complexes with many food and drink stalls" while food courts were defined as air-conditioned food establishments.

The researchers reiterated that the focus of the study was to provide an "in-depth regional analysis of food prices" at the time of data collection, which was between September to November last year, and not on price differences between 2022 and 2023.