washingtonpost.com

COP26 in Glasgow may have a record carbon footprint, despite low-flush loos and veggie haggis

William Booth, Harry Stevens

6-8 minutes

GLASGOW, Scotland — The British government promised to host a

carbon-neutral climate conference, but even after all the showy sustainability — the reusable coffee cups, the low-flush loos, the paperless draft documents, the locally sourced vegetarian haggis — COP26 may be the highest emitting United Nations environmental summit so far.

How much is 102,500 tons of carbon dioxide equivalents? Consider that the average Briton emits 12.7 tons a year, while the average Sri Lankan produces 1 ton of CO2e annually.

This COP is bigger than the previous iterations, with nearly 40,000 registered participants, including delegates, observers and media. But asked why the carbon footprint was larger than in previous years — both in terms of total and per-participant emission — the British government told The Washington Post that it was partly because of how it defined what emissions were associated with the summit.

For the first time, the government said in a statement, the calculation includes not just the conference site, which is open to credentialed participants, but also the “Green Zone,” a space across the river for civil society events.

The lights and heat are having to stay on a bit longer, as negotiators continued talking past a Friday evening deadline. The final emissions tally will not be known until after the summit is over, the government noted.

Whatever it is, it will reflect just how hard it is for the world to wean itself off fossil fuels.

To offset these emissions, the British government said it will purchase carbon credits. It did that, too, to offset the

20,200 tons of carbon dioxide equivalents produced by the three-day G-7 summit in Cornwall, England, in June. The government wrote checks to pay for:

- Improved cook stoves in India.

- Methane capture at a solid-waste treatment facility in Vietnam.

- A hydropower project in Laos.

- Biogas electricity generation in Thailand.

- Fuel-efficient rolling stock for the New Delhi metro.

There will be funding for similar projects to offset COP26. But both Arup and the government declined to say how much Britain paid or will pay per ton for carbon offsets — which goes against the pledge that certification of carbon neutrality be as transparent as possible.

No matter — it is possible to guesstimate the cost.

Sarah Leugers, communications director for

Gold Standard, a Geneva-based organization that provides certification standards for offset projects, said credits these days cost about $7.50 a ton — though, depending on the project, can be as low as $3 or $4 (for renewable energy) or as high as $10 (for “nature-based solutions,” like

peat restoration).

Assuming Britain pays $7.50 for each of the 102,500 tons of emissions, the carbon tab for COP26 would come to $768,750.

Which sounds like a lot — or a little?

If all 40,000 attendees were presented with a bill, they would owe less than $20 each.

Considering that a mediocre hotel in Glasgow was asking $300 or $400 a night, it seems like a steal.

Delegates are seen at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26), in Glasgow, Scotland, Britain November 12, 2021. REUTERS/Yves Herman (Yves Herman/Reuters)

The pandemic has reduced the carbon footprint of other recent major events, said David Stubbs, owner of green advisory Sustainability Experts. Organizers of the Tokyo Olympics, for instance, limited both the spectators and support staff that could come in, to lower the risk of

coronavirus transmission.

Videoconferencing and other virtual technology has also cut down on big events’ carbon footprint, Stubbs said. “I would have expected this to be the case at COP26,” he added, “but it does seem that enormous numbers of people have turned up in Glasgow.”

Organizers have tried to manage coronavirus risk here with requirements for masks and daily testing.

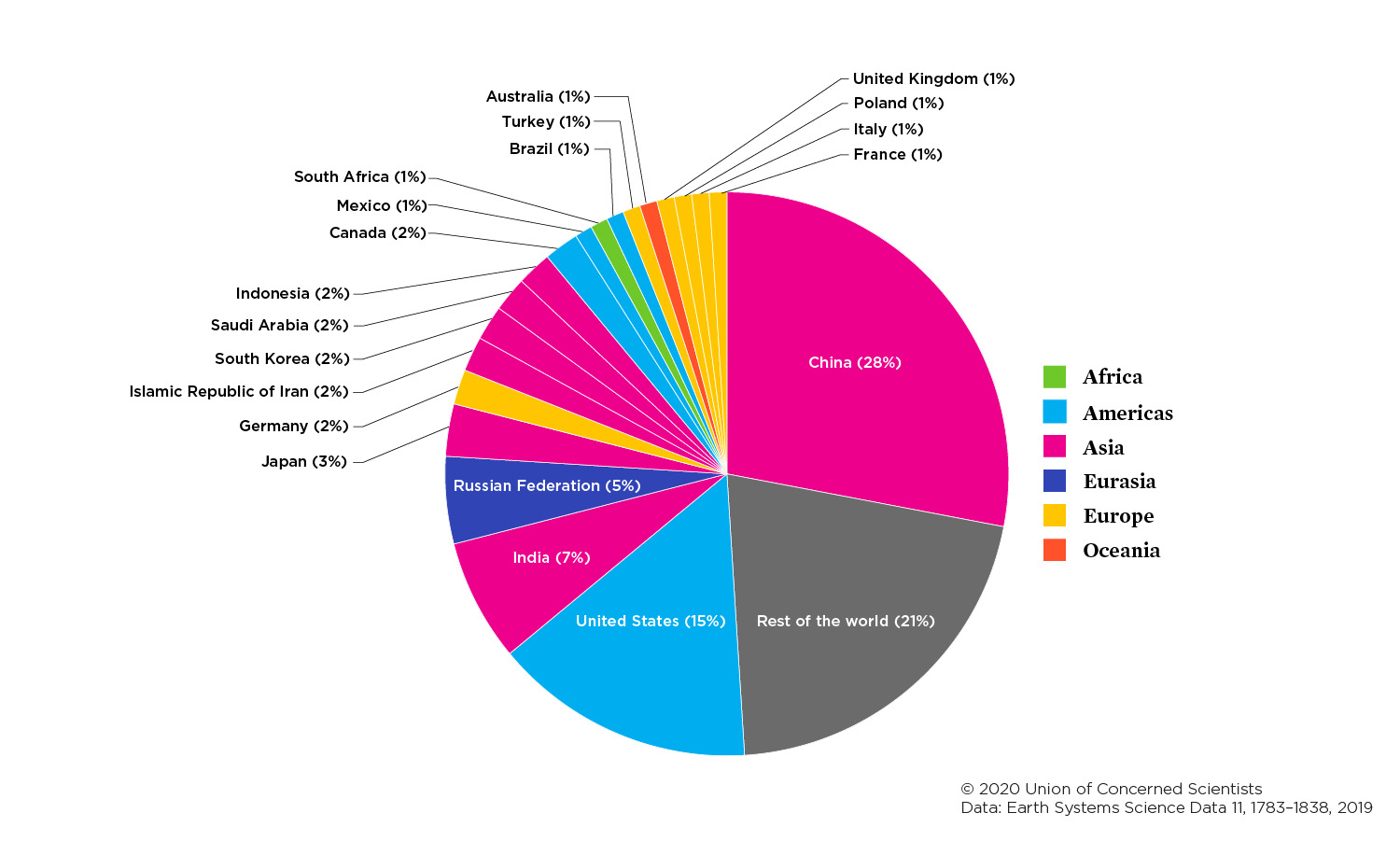

Arup estimated that more than 60 percent of emissions from the Glasgow meeting will come from air travel. The second-largest source is accommodation.

All those world leaders, all those planes.

And all those delegates, official observers and accredited journalists, too.

The conference’s host, Prime Minister Boris Johnson, was shamed for his personal spike in carbon emissions.

Johnson arrived in Glasgow at the start of the summit via

chartered Airbus A321 jet. That was understandable, as he was coming directly in from the Group of 20 summit in Rome. Less easily excused: He returned home to London from Glasgow — a 400-mile hop — by the same airplane.

His office blamed time constraints and noted that the jet used 35 percent sustainable aviation fuel. “Our approach to tackling climate change is to use technology so that we do not have to change how we use modes of transport, rather we use technology on things like electric vehicles, so that we can still get to net zero,” a Downing Street spokesman said.

A protester wears a caricature head of British Prime Minister Boris Johnson during a protest near the venue of the COP26 U.N. Climate Summit in Glasgow, Scotland, on Friday. (Scott Heppell/AP)

Sustainability advocates were not impressed. After taking much heat, the prime minister managed to find time to go back and forth by train when he returned to Glasgow this week.

It is hard to see how most delegates could have gotten to a world summit on climate without jet travel — and the U.N. and British hosts both thought it vital that delegates attend in person, as negotiating the deal requires a lot of talk and compromise.

But there’s always coach. Actor

Leonardo DiCaprio flew commercial to Edinburgh, his people said.

Dan Rutherford, aviation director at the International Council on Clean Transportation, said a round-trip flight from Toronto to Glasgow would emit 630 to 740 kilograms of carbon dioxide for a coach seat.

Want to fly business class? That seat emits 2.6 to 4.3 times more greenhouse gas. Private charter? Those aircraft emit 10 times more per passenger, Rutherford said.

The COP26 organizers did go to some lengths to shrink the footprint.

They used fuel-efficient heating. They encouraged attendees to walk — and provided free bus and train passes for those staying farther away. Around the halls, they scattered Ikea chairs that afterward will go to charities or community projects. The caterers served locally sourced and in-season produce and increased the proportion of plant-based dishes. There was an ambulance on scene run on green hydrogen.

Britain celebrated getting so many people to Glasgow, to focus on the climate emergency, even in the middle of a pandemic.

Which is a good thing — but comes with a carbon cost.