- Joined

- Jul 10, 2008

- Messages

- 66,360

- Points

- 113

Study claims some cancers 'better left undiscovered'

Liam Mannix13:23, Jan 27 2020

The impact of a cancer diagnosis

When 26-year-old Katharina was diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer, it turned her life upside down. But she did her best to stay positive.

A controversial new study claims about one in every five cancers diagnosed in Australia would have been better left undiscovered.

The study, published in the Medical Journal of Australia on Monday, argues more than half of melanomas, 22 per cent of breast cancers and 42 per cent of prostate cancers diagnosed in Australia would never have caused problems.

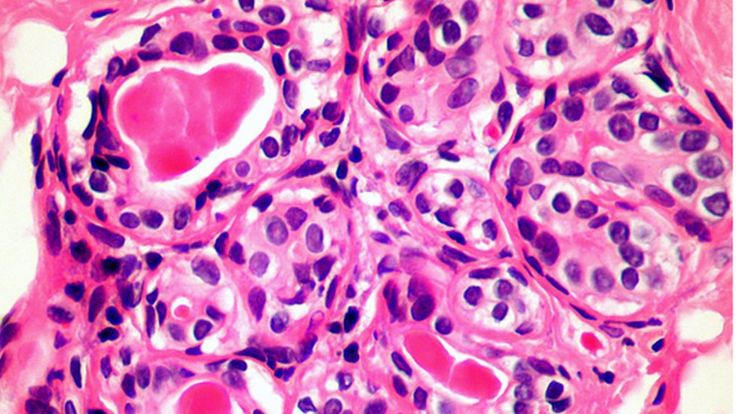

JEMS STEM A prostate cancer cell. The Australian study team has proposed two solutions to the overdiagnosis of cancer.

The government funds a breast-cancer screening program and many people diligently ask their GP for skin and prostate cancer checks.

But all that extra checking is turning up cancers that would never have gone on to harm the patient, the study says.

The model and body positivity advocate says she "knew that surgery would be life changing but I never knew it could change my life in such a positive way".

READ MORE:

* Chasing the ultimate dream: Kiwi scientists work on breast cancer vaccine

* Cervical screening 'needs to be part of everyday conversation'

* Cancer blood tests 'very close', as scientists develop the technology

* Why are Kiwi men in some regions twice as likely to die of prostate cancer?

And to treat them, we turn to surgery and chemotherapy – which come with their own risks.

"There will be cancers diagnosed that will not go on to be life threatening," concedes Cancer Council CEO Professor Sanchia Aranda.

"But the issue remains that we don't always know which cancers are overdiagnosed and which cancers pose a real threat.

"Not diagnosing a cancer and having a woman die would be considered a bigger harm that the damage of getting a cancer diagnosis that was of a cancer that might not have harmed you."

To come up with the calculation, the Bond University-led team compared cancer rates between 1982 and 2012 - a time in which our cancer incidence rate rose by about 30 per cent while our cancer death rate fell.

They studied only five cancers which are known to be overdiagnosed: breast, prostate, renal and thyroid cancer and melanoma.

After adjusting for risk factors that had changed over the years, the researchers concluded much of the increase in cancer could be explained by doctors finding more harmless cancers.

Assuming that other cancers were not being overdiagnosed - which may or may not be the case - they came to a final figure of 18 per cent of all cancers in women, and 24 per cent of those in men, being overdiagnosed.

Breast cancer screening is a particularly difficult case because doctors often cannot tell if the cancer they find will be harmless or life threatening. To be safe they treat them all the same: with surgery or chemotherapy.

In the UK, women receive a leaflet before they get their mammograms.

For every 200 women screened, one will have her life saved, the leaflet says. But three will undergo unnecessary surgery for a cancer that never would have caused symptoms.

Ultimately, "it is your choice," the pamphlet concludes.

British Medical Journal editor Fiona Godlee is among high-profile scientists who weighed those odds and decided to skip screening.

"I struggle with it, I really, really struggle with it," says Professor Alexandra Barratt, one of the study's authors and a breast-cancer screening researcher at the University of Sydney.

"There are potential benefits and potential harms – and I am very concerned about the risk of being overdiagnosed and overtreated."

Bond University's Professor Paul Glasziou led the study. He says an explosion in skin cancer screening has led to huge numbers of harmless moles being cut out. Some of that may be driven by financial reasons; look at the number of new mole-screen clinics appearing, he says.

And prostate cancer is overdiagnosed. The Royal Australian College of GPs now recommends against prostate cancer screening.

"I'm 65, there is about a 50 per cent chance that if you sliced up my prostate you'd find cancer," Professor Glasziou says. "And the vast majority of those would not cause a problem in a person's lifetime."

The study team proposes two solutions to overdiagnosis: research to develop better tests for cancer, and information campaigns – like the one in the UK – to warn people of the pros and cons of screening.

A 2015 study on 879 women in the state of New South Wales found when they were told about overdiagnosis risks, only about 74 per cent planned to get screened. In women who were not told, that number was 87 per cent.

Sydney Morning Herald

Liam Mannix13:23, Jan 27 2020

The impact of a cancer diagnosis

When 26-year-old Katharina was diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer, it turned her life upside down. But she did her best to stay positive.

A controversial new study claims about one in every five cancers diagnosed in Australia would have been better left undiscovered.

The study, published in the Medical Journal of Australia on Monday, argues more than half of melanomas, 22 per cent of breast cancers and 42 per cent of prostate cancers diagnosed in Australia would never have caused problems.

JEMS STEM A prostate cancer cell. The Australian study team has proposed two solutions to the overdiagnosis of cancer.

The government funds a breast-cancer screening program and many people diligently ask their GP for skin and prostate cancer checks.

But all that extra checking is turning up cancers that would never have gone on to harm the patient, the study says.

The model and body positivity advocate says she "knew that surgery would be life changing but I never knew it could change my life in such a positive way".

READ MORE:

* Chasing the ultimate dream: Kiwi scientists work on breast cancer vaccine

* Cervical screening 'needs to be part of everyday conversation'

* Cancer blood tests 'very close', as scientists develop the technology

* Why are Kiwi men in some regions twice as likely to die of prostate cancer?

And to treat them, we turn to surgery and chemotherapy – which come with their own risks.

"There will be cancers diagnosed that will not go on to be life threatening," concedes Cancer Council CEO Professor Sanchia Aranda.

"But the issue remains that we don't always know which cancers are overdiagnosed and which cancers pose a real threat.

"Not diagnosing a cancer and having a woman die would be considered a bigger harm that the damage of getting a cancer diagnosis that was of a cancer that might not have harmed you."

To come up with the calculation, the Bond University-led team compared cancer rates between 1982 and 2012 - a time in which our cancer incidence rate rose by about 30 per cent while our cancer death rate fell.

They studied only five cancers which are known to be overdiagnosed: breast, prostate, renal and thyroid cancer and melanoma.

After adjusting for risk factors that had changed over the years, the researchers concluded much of the increase in cancer could be explained by doctors finding more harmless cancers.

Assuming that other cancers were not being overdiagnosed - which may or may not be the case - they came to a final figure of 18 per cent of all cancers in women, and 24 per cent of those in men, being overdiagnosed.

Breast cancer screening is a particularly difficult case because doctors often cannot tell if the cancer they find will be harmless or life threatening. To be safe they treat them all the same: with surgery or chemotherapy.

In the UK, women receive a leaflet before they get their mammograms.

For every 200 women screened, one will have her life saved, the leaflet says. But three will undergo unnecessary surgery for a cancer that never would have caused symptoms.

Ultimately, "it is your choice," the pamphlet concludes.

British Medical Journal editor Fiona Godlee is among high-profile scientists who weighed those odds and decided to skip screening.

"I struggle with it, I really, really struggle with it," says Professor Alexandra Barratt, one of the study's authors and a breast-cancer screening researcher at the University of Sydney.

"There are potential benefits and potential harms – and I am very concerned about the risk of being overdiagnosed and overtreated."

Bond University's Professor Paul Glasziou led the study. He says an explosion in skin cancer screening has led to huge numbers of harmless moles being cut out. Some of that may be driven by financial reasons; look at the number of new mole-screen clinics appearing, he says.

And prostate cancer is overdiagnosed. The Royal Australian College of GPs now recommends against prostate cancer screening.

"I'm 65, there is about a 50 per cent chance that if you sliced up my prostate you'd find cancer," Professor Glasziou says. "And the vast majority of those would not cause a problem in a person's lifetime."

The study team proposes two solutions to overdiagnosis: research to develop better tests for cancer, and information campaigns – like the one in the UK – to warn people of the pros and cons of screening.

A 2015 study on 879 women in the state of New South Wales found when they were told about overdiagnosis risks, only about 74 per cent planned to get screened. In women who were not told, that number was 87 per cent.

Sydney Morning Herald