- Joined

- Aug 29, 2008

- Messages

- 27,393

- Points

- 113

The Underground Cooks of Singapore’s Prisons

In the 1970s and 80s, when the guards stepped away, the pots and flames came out.

BY SAM LIN-SOMMERJANUARY 12, 2023

In the 1970s and 80s, illicit cooking sessions known as "masak" were widespread in Singaporean prisons and rehabilitation centers. EYEEM/ALAMY

SHRIMP SAMBAL, RECONSTITUTED MILK, AND fried noodles bubble away in a pot, filling the air with the aroma of laksa, Singapore’s beloved noodle soup. For the cooks working in careful silence, the smell is a reminder of life outside of the prison they are stuck in, and it is hard-won: To make the dish, one man lit a flame on a candle made of his T-shirt and a melted-down food tray; another purchased the can of sambal from the commissary before scraping it open against the concrete wall; while yet another sacrificed the noodles of his paltry prison lunch.

In 1970s and 1980s Singapore, scenes like this abounded in men’s prisons and Drug Rehabilitation Centers (DRCs). Behind guards’ backs, many men smuggled ingredients to secretly cook in their barracks on makeshift stoves during kitchen jam sessions that were so common they had their own nickname: masak, which means “to cook” in Malay.

“Masak provided a space for autonomy, despite the circumstances,” explains Singaporean food writer Sheere Ng in When Cooking Was a Crime: Masak in the Singapore Prisons, 1970s-80s. In institutions that could tell a person how to dress, how to behave, and what to eat, cooking became a means of self-expression.

Ng began researching masak after hearing about the practice from a formerly incarcerated Singaporean restaurateur. She tracked down eight men who were incarcerated during the period and each of them revealed during his interview that he had participated in masak. Her reporting led her to believe that masak was widespread.

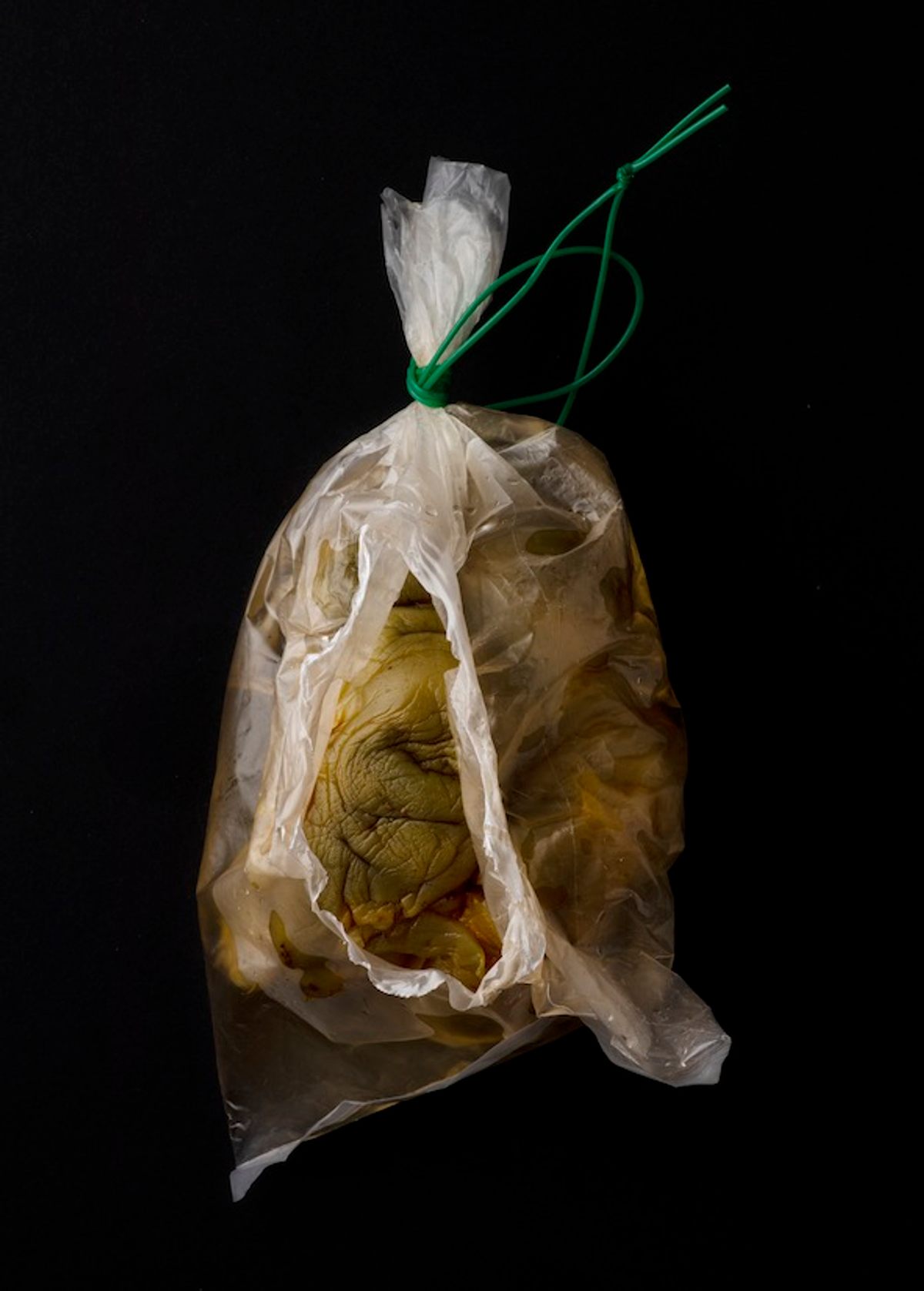

Denied access to utensils, fuel, and most ingredients, incarcerated cooks—most of whom had little prior experience—devised ingenious cooking methods. They would make bubbling stews from ingredients such as commissary anchovies, luncheon meat reserved from prison lunch, and clean toilet bowl water, heating them over makeshift fuel such as plastic bags and cut-outs of blankets that they rolled together and set aflame.

In DRCs, cooks would light cotton balls with razor blades struck against flint. Networks of bribed guards and other incarcerated men smuggled ingredients and cooking supplies out of clinics, workshops, and kitchens, often along gang networks.

For the freshest ingredients, men hunted and foraged on prison and rehabilitation center grounds. Many of the latter were located in jungles. Several of Ng’s interviewees described a roadside mango tree that hung over the yard of a DRC.

They picked the mangoes and pickled them in salt, sugar, and water from a cleaned toilet bowl. Men in DRCs would also hunt rabbits that had wandered into the yard, and catch pigeons by scattering breadcrumbs in patches of grass laced with needles.

These exploits succeeded because prisoners were less surveilled than their modern-day counterparts. The prisons and DRCs of the 70s and 80s were scattered across the island in the former barracks of the British Army. “These facilities weren’t built for surveillance,” Ng says. Singapore, a nexus in Southeast Asia’s “Golden Triangle” of drug trafficking, began arresting huge numbers of people for drug- and gang-related charges starting in the 70s, and couldn’t hire enough prison staff to keep up. Many guards were not comfortable writing in English, the country’s official language, so many avoided checking on the captees for fear of having to write a report.

Still, as Ng’s book title attests, cooking was not allowed within prison walls. Masak cooks risked additional charges such as theft, possession of forbidden property, and destruction of prison property if they were caught. Such infractions could mean solitary confinement, and an extension of their prison sentence. To avoid being detected, cooks waited until they were left alone for the night, and made sure to only cook when lenient guards were on patrol.

For their bravery, incarcerated cooks were rewarded with a momentary escape. They found nostalgia in hot, boiled dishes that, in addition to being easy to make, reminded them of their lives outside of prison. “After that you lie down on the floor, smoke a cigarette, you [feel like] are not in prison, you know!” Ng recounts one interviewee telling her in When Cooking Was a Crime.

In addition to escape, masak offered camaraderie to men torn from the social fabric of home. Cooks brought food to newcomers who had trouble adjusting, and baked cakes made of melted chocolate, margarine, and soda biscuits to those celebrating their birthdays. Men with more money would shoulder the cost of commissary items, and those who already had served close to the maximum prison sentence of 36 months would take the blame for those with more to lose. As one former masak cook told Ng, “We won’t ge gau (“to be miserly” in Hokkien) because we are all under one banner.”