The PAP government did set a 10 million population goal.

It denied it in the face of fierce resistance.

But the PAP is not letting go of this policy.

It is now reviving it again.

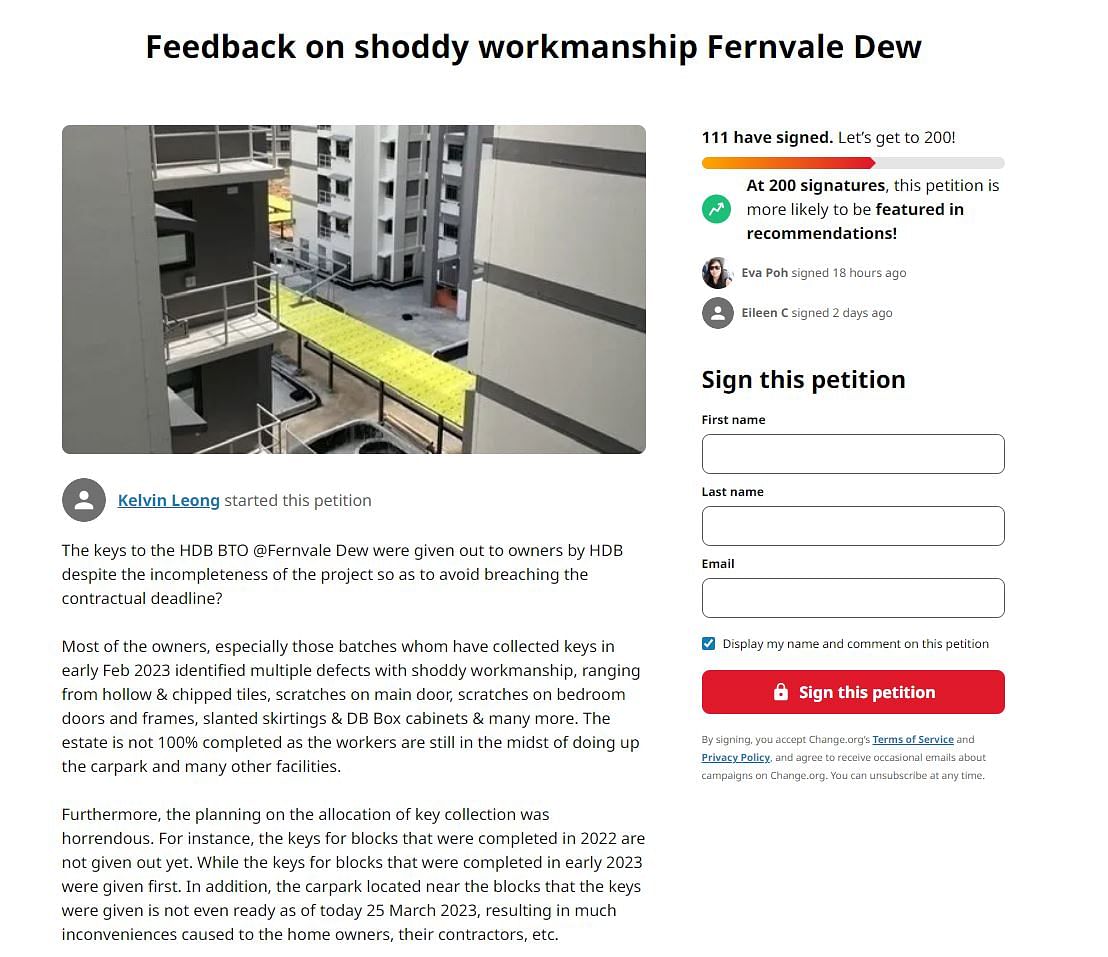

Say hello to BTO flats starting at $1 million for first-time HDB flat owners.

But kiss the PAP government's ass because they are subsiding $1 million.

Revisiting the Singapore population size debate

With birth rates falling to historic lows, it’s time we take a hard-headed look at how to remain a vibrant city, and the critical role of immigration in this mission

Zakir Hussain

Associate Editor

Singapore may not be near a population of 10 million, but it would be prudent to plan for that density in mind. ST PHOTO: DESMOND WEE

MAR 19, 2023

Ten years ago, Singapore saw a rather unprecedented public outcry at the suggestion that 6.9 million people might one day inhabit this island.

A Population White Paper that had cited this figure

as a planning parameter – not a target – for around 2030 saw strong protests from segments of the public and ruling party backbenchers.

The ensuing parliamentary debate saw the Government acknowledge ground concerns over the pace of population growth and immigration, and commit that the conversation would continue.

Two months after the heated debate, a former chief planner suggested that Singapore look beyond 2030.

The country could do well to look ahead, perhaps to 2100,

when it might have a population of 10 million, suggested Mr Liu Thai Ker at a forum in April 2013.

“The world doesn’t end in 2030, and population growth doesn’t end at 6.9 million,” he said.

Mr Liu, who used to head the Housing Board and Urban Redevelopment Authority, returned to the 10 million figure at another forum in July 2014.

The Republic should plan for a population this size in the long term if it is to remain sustainable as a country, he added.

The 10 million figure did not generate as much heat then, perhaps because Mr Liu was offering his thoughts in a less formal setting, and he had not been in government for some time.

It is hard to imagine a Singapore with 10 million people, even if it is decades away.

Mr Liu had noted that if the growth rate were based on the upper limit of the 2013 White Paper’s projections, at 6.9 million in 2030, Singapore could reach a population of 10 million by 2090.

But if it is based on the lower limit of 6.5 million in 2030 – a range we are quite far from today – then it may reach 10 million by 2200.

Mr Liu also acknowledged that Singaporeans may be uncomfortable with the thought of the country ever having a population that size.

But, to paraphrase Mr Liu, isn’t it better to plan for the longer term with this in mind, so that if or when Singapore reaches that level of density, it will remain vibrant and liveable because the infrastructure is in place?

Big city competition

Singaporeans are not unfamiliar with large metropolises of over 10 million.

Many have been to Bangkok, Jakarta, Manila and Ho Chi Minh City, vibrant economic centres of a fast-growing region.

All have one thing in common – they are magnets for manpower and talent from their respective countries. They are also growing rapidly, and their buzz and energy are palpable.

New York City and London each has more than eight million people in their city boundaries, and are also magnets for talent from around the world.

But many of these cities are also straining to catch up with infrastructure improvements and the challenge of urban renewal, some of which could have been avoided with long-term planning.

There is also a degree of tension between more settled, better-off residents and newer, less well-off arrivals, who may share a nationality but not the same outlook on the world.

Even if Singapore is nowhere near a population of 10 million, it must prepare to hold its own against these competitors with more land around them, and a larger talent pool. Some might point out that Singapore is just over 700 sq km. But its longer-term plans provide for substantial green lungs and nature reserves. By comparison, Jakarta has more than 10 million residents spread out over 660 sq km and New York City’s more than eight million residents are spread out over 800 sq km, and it still has a sizeable spread of parks.

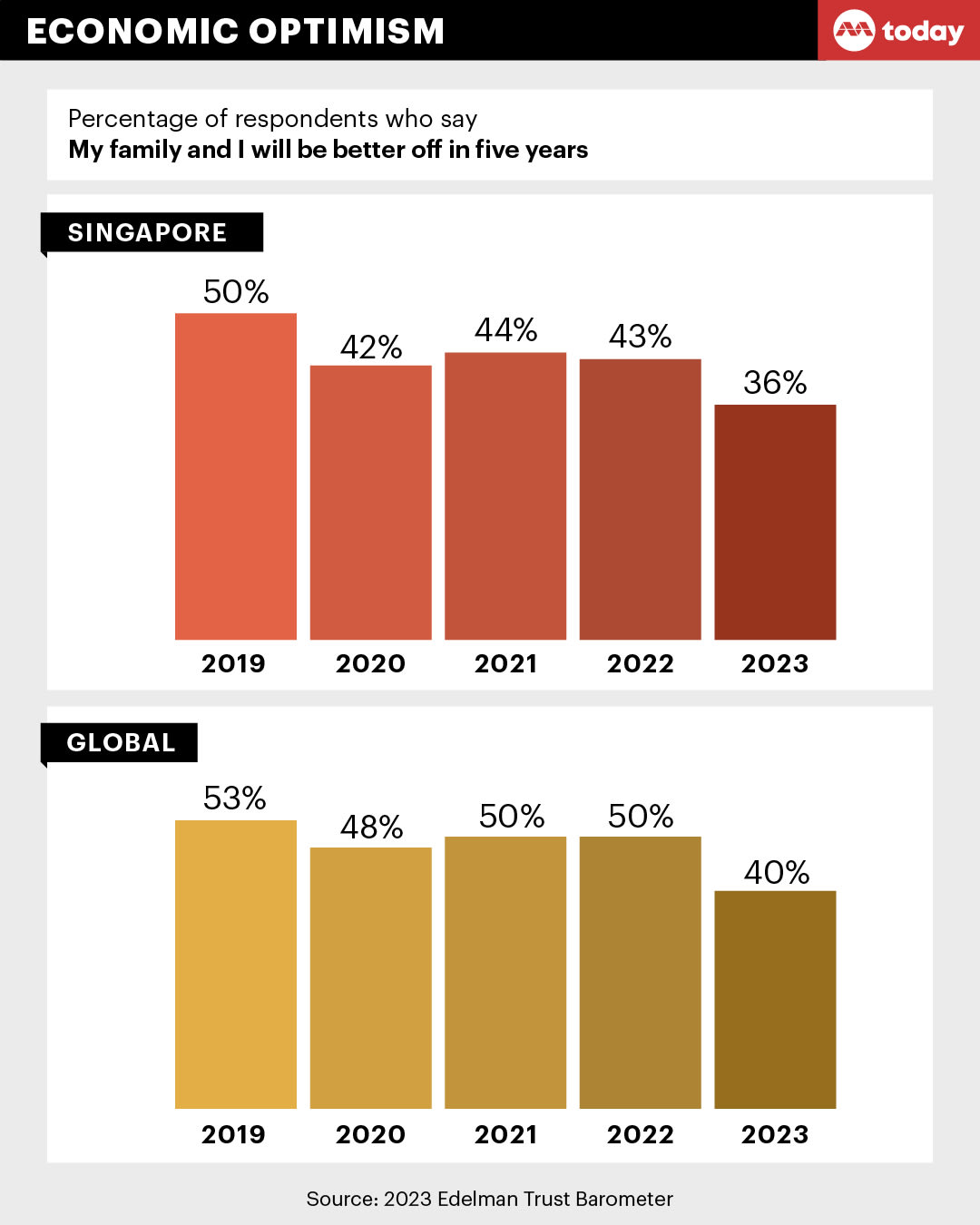

A decade after the population debate, Singapore is a long way away from a population of 6.9 million, let alone the 6.5 million the White Paper said it could reach with slower population growth.

The country’s population rose rapidly from 1.6 million in 1960 to three million in 1990, and crossed five million in 2010.

But the Covid-19 pandemic saw the population fall for two straight years – from 5.7 million in 2019 to 5.69 million in 2020,

and to 5.45 million in 2021.

While the drop was due to a decline in the non-resident population, resident numbers are also growing at a slower pace.

The White Paper had projected the total population to be between 5.8 million and six million by 2020, depending on fertility trends, life expectancy, and social and economic needs. It had also projected the resident population to be between four million and 4.1 million that year, with citizens numbering some 3.5 million to 3.6 million.

As at June 2022, the total population

had climbed back up to 5.64 million. Singapore citizens numbered 3.55 million, and with another 520,000 permanent residents, brought the total resident population to 4.07 million.

The recent economic recovery and ongoing infrastructure projects mean the number of non-resident workers can be expected to grow in the coming years.

At the same time, the Government has continued to maintain its commitment to safeguarding a Singapore core to the population.

ST ILLUSTRATION: CEL GULAPA

A shrinking pool

But declining birth rates mean the core of citizens has to be topped up through immigration.

Singapore’s total fertility rate

reached a historic low of 1.05 in 2022, well below the 2.1 needed for the population to replace itself.

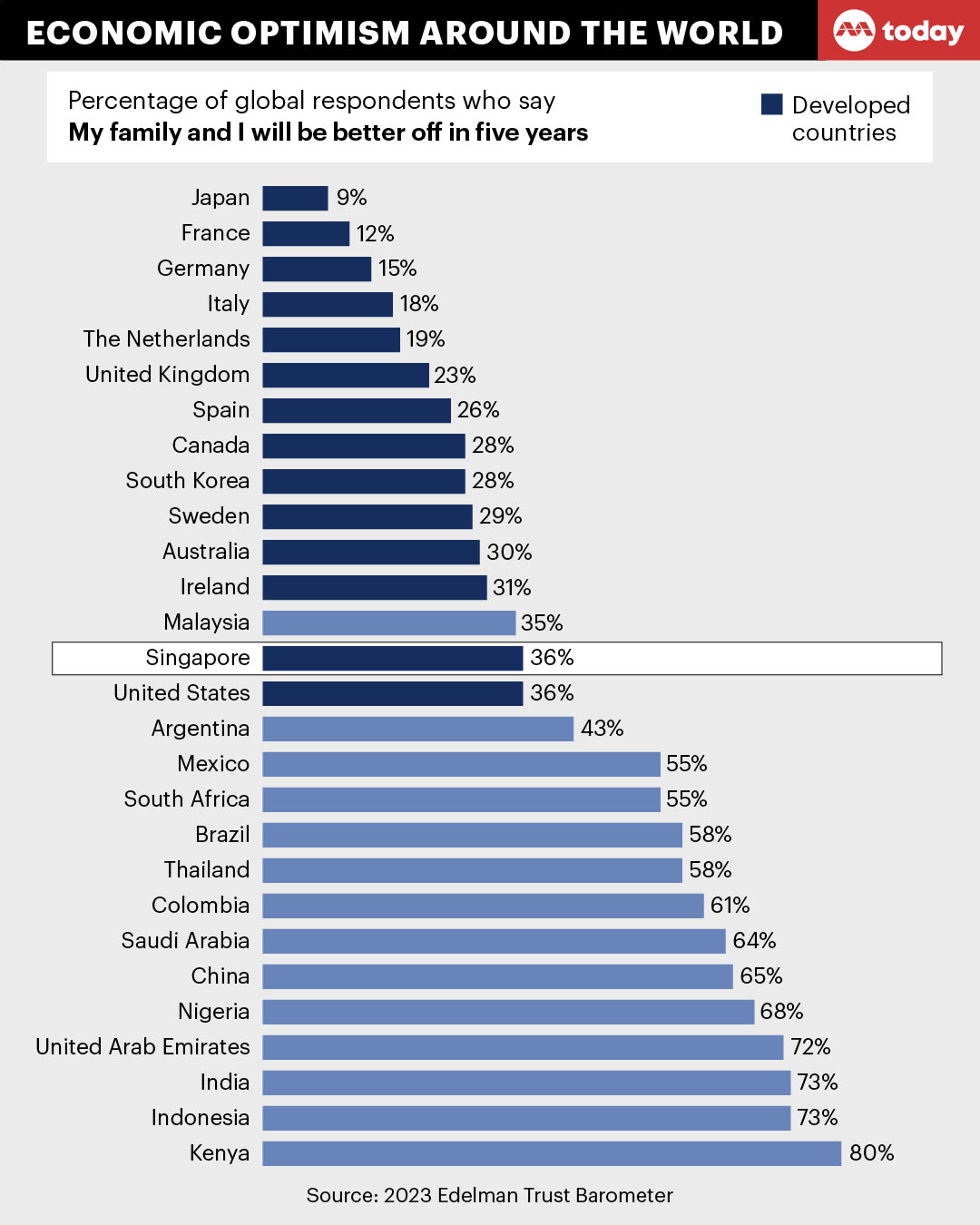

Similar record lows are seen in the region, with

South Korea’s birth rate at 0.78, and Japan’s at 1.3.

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida

told his country’s MPs in January that the dismal birth rates meant the country was “standing on the verge of whether we can continue to function as a society”.

Earlier in March, his aide Masako Mori said the

country would “disappear” at current falling birth rates. “A nosedive means children being born now will be thrown into a society that becomes distorted, shrinks and loses its ability to function,” she added.

Japan’s situation is a cautionary example of what could happen when the immigration tap is too tight, or hardly turned on.

Singapore is trying to work on raising its birth rate. But it has also been able to complement its population by being able to attract and integrate new arrivals, some of whom go on to apply to be permanent residents and eventually citizens. Many of them come from the immediate region.

This could prove more challenging as the region’s economies become more vibrant, making it less compelling for their people to look abroad for a brighter future.

Singapore’s neighbours are also seeing record low fertility.

Thailand saw the lowest birth rate in 70 years last year, and Malaysia’s birth rate has dropped below replacement level.

Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam also saw fertility rates at or around the replacement level of 2.1.

Could there be implications for Singapore’s ability to continue attracting talent from the region?

In 2022,

Singapore granted about 23,100 new citizenships, including about 1,300 to children born overseas to Singaporean parents. About 34,500 new permanent residents were accepted.

Giving an update to Parliament on these figures in February, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office Indranee Rajah said they were higher than pre-Covid-19 levels as some approved applicants could not complete the process in person in 2020 and 2021, and their applications were carried over.

Many of these new citizens have been PRs for some time, yet to some, distinctions continue to be drawn over “true-blue” or “born-and-bred” Singaporeans and newer citizens and residents.

This has led to some wondering if Singapore is losing some of its attractiveness and openness to talent.

Anti-foreigner sentiments

Politics has invariably coloured some of these perceptions, as various quarters seek to tap into anti-immigrant sentiment, some of which has spilled over to Singaporeans from smaller minority groups and naturalised citizens.

The 10 million figure resurfaced in the 2020 General Election, when several opposition parties alleged that the Government planned to raise the population to 10 million by bringing in more foreigners.

The National Population and Talent Division (NPTD) issued a clarification categorically stating that these statements were untrue.

“The Government has not proposed, planned nor targeted for Singapore to increase its population to 10 million,” it said then, adding that it does not seek to achieve a particular population size.

In February, Ms Indranee also told Parliament that based on various scenarios, it remains the case that the total population is likely to be significantly below 6.9 million by 2030.

She also acknowledged that the issue of immigration had to be managed delicately.

“We have seen how tensions over immigration in other countries have led to fissures and divisions in society. We must not let that happen here in Singapore,” she said.

“While most Singaporeans understand why we need immigrants, there are, understandably, concerns over competition for jobs and other resources, and how the texture and character of our society could change, and whether our infrastructure can keep up.”

Today, infrastructure continues to be ramped up – with new MRT lines, a major highway and HDB towns under construction after a slight delay caused by the pandemic.

Planning isn’t all inward-oriented: The expansion of Changi Airport and the construction of Tuas Megaport well into the 2030s aim to cater to double the passenger and container volumes handled today.

Changi and Singapore’s port are not just major anchors and engines of the economy that were affected by the pandemic and have begun their recovery. They are also symbols of Singapore’s interconnectedness with the world, and of its commitment to staying open in a world beset by rising geopolitical tensions and uncertainties.

There is a high threshold for aspiring immigrants and would-be residents, and recent measures on Singapore’s part aim to compete for a slice of the global talent pie.

But the window of opportunity to attract top talent may be a narrow one.

Shying away from being more open and embracing of newcomers could mean missing out on a stronger footing for the long run, and not building the best possible team for Singapore.