In Russia, North Korean laborers risk death for a chance to earn cash

Seol Song Ah | 2016-07-27 14:53

North Koreans dispatched abroad as laborers suffer from all types of human rights abuses and labor rights violations. Recently we had the opportunity to speak with Choi Cheol (pseudonym), who was sent to Russia and worked as a logger until 2010. There, the worksites are dangerous, the work is backbreaking, and the authorities demand exorbitant bribes. Laborers begin their 12-hour shifts at 5:00 am. The temperature regularly dips to minus 20-30 degrees Celsius during the winter season. After toiling under such conditions, Choi Cheol eventually decided to defect, and today he has resettled in America.

Below is an English transcript of the interview.

Daily NK [DNK]: I understand that it isn’t easy to get work as an overseas laborer in Russia. Is that so?

Mr. Choi [Choi]: Being able to leave the defunct North Korean economy was indeed a stroke of luck. Residents who want to leave need to save up a lot of money so they can bribe the relevant officials.

In the late 1990s, the North Korean authorities began selecting residents in each province, city, and county to work as loggers in order to solve the state economic emergency. Residents tried their best to provide for their families despite the fact that the public distribution system was broken. Some sold all of their belongings to bribe officials so they could have a chance to earn a living overseas.

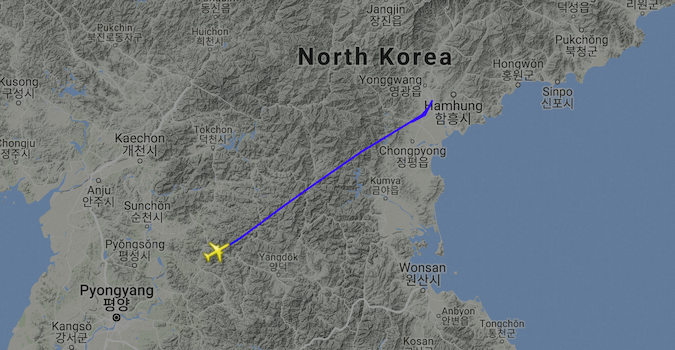

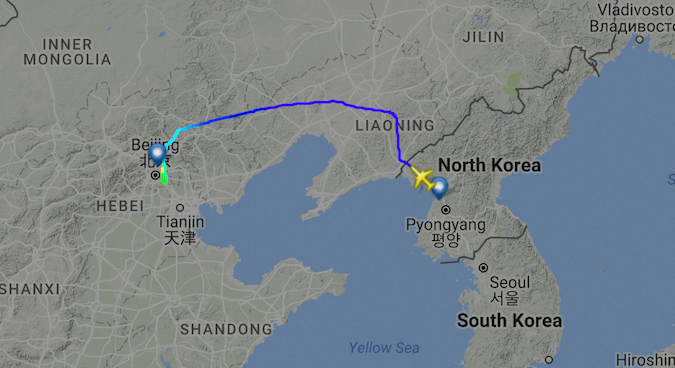

The procedure for getting the green light to work as a foreign laborer involves receiving permissions from the Ministry of People’s Security (police), the hospital health inspector, the state factory manager, the local inminban head (people’s unit), and the State Security Department. Bribes must be issued to people in each and every one of these departments to receive permission. In interviews, it was revealed that the largest bribe goes to cadres from the central party. Despite the cost, residents nonetheless see overseas work as a potential solution to their economic hardship. That’s why they’re willing to fork over so many bribes. That’s how, in 2000, I ended up boarding the Trans-Siberian Railway with my colleagues for a three-day, two-night journey into Russia.

DNK: You must have had big expectations at that point. Were you informed about your wages before you left?

Choi: North Korea completely ignores employment contracts. Before going to Russia, the provincial Party cadres informed me that when forestry production normalized, I could expect to receive an average of US $300 per month. With that in mind, I calculated that I could make $10,000 over the course of my contract (the standard three year term). When I considered the costs of food and lodging, I thought I could take home at least $5,000. I realized after six months that the reality would be totally different from this inflated expectation.

The money that was put in my hand at the end of the month was closer to $70-$80. And that was what we received in the winter. Winter production lasted from October until May. We worked extremely hard during that time. However, 40% of our wages went to the State Forestry Administration, 20% to the affiliated state-run enterprise, and 15% went to the production unit’s operational funding. The remaining 25% went to the laborers.

During the summer, we went to the lumber worksites to set up the facilities and equipment, including tools and vehicles. Our wages were cut in half during this period.

[DNK]: How did you manage to survive on such a low income during the summer season? Did the authorities at least guarantee room and board?

Choi: Daily necessities and food are provided for. The enterprise provided rice, soybean paste, salt, soy sauce, and work clothes. However, the cost of these items was deducted from our wages. So in truth, the authorities are providing a building, and everything else comes out of our paycheck. To save money, laborers sometimes make side dishes using mushrooms, plantains, and dandelions. Laborers will also gather up scrap metal and wild greens to sell to locals as a way to earn some extra cash.

It seems funny to say it now, but there was a place called “Crow Hill.” It was a village dumping ground covered with garbage like food scraps and garments. The sky above was swarming with crows. We used to go there often to pick up clothes and products. We spotted some old television sets. Some people were able to scavenge some of the parts to sell upon their return to North Korea.

We were so afraid of losing our money. Each small bit was precious. Without money, we would be in trouble. So, outside of shower time, we made sure to always have it on us. After three years of storing the money on our person continuously, it started to stink of sweat.

DNK: Are there any safety precautions or procedures at the worksites?

Choi: Protecting residents who leave the country is one of the government’s fundamental duties. North Korea, however, does not take this responsibility seriously. The authorities value the life of a laborer just as much as they value the life of a fly. As a result of this nonchalant attitude, accidents are common on worksites.

Sometimes logs fall on the laborers. The logs sometimes crushed laborer’s legs. The authorities do not provide any compensation or health services. Instead, they send injured workers home empty handed. In a single moment, these poor laborers are transformed into handicapped people and immediately get sent away.

Some workers fall from high heights resulting in concussions. Others are too immersed in their work to avoid a falling tree. People have died upon impact from such injuries. There was also an incident when dozens of workers died together. They made temporary lodging because they were deep in the forest. They got caught in a forest fire while they were sleeping.

One laborer went into town to buy some food supplies when he was confronted with a drunken local. The local was wielding a deadly weapon, and he ended up killing the laborer. That made the workers quite upset, especially because the North Korean authorities did not demand a just response from the Russian government. Even now, when I think about that, I get angry. The authorities were so obsequious and inhumane. I get the most upset when I recall how my colleagues frozen, dead bodies were loaded up on a train.

DNK: How do the authorities deal with workers who leave the worksite?

Choi: Some people pile up huge amounts of debt because they buy food to survive and alcohol to warm their bones. Returning to North Korea without any money at all is an unbearable thought. Most laborers have parents and family members who are waiting expectantly for their return. It is not even worth asking the enterprise for assistance, so in cases like this, the workers usually end up pursuing work outside of the worksite.

They pour all their energy and concentration into earning money. It is a dangerous situation--they don’t even have identification cards-- but netting a profit is easier than at the worksite because one’s income is tied to one’s work hours. However, if you get caught by the Russian police and turned over to North Korean representatives, all of this income gets confiscated. Furthermore, the worker will thereafter get sent to a forced labor camp near the [North Korea-Russia] border for a period of three months. Only when the worker is on death’s door is he released.

At that point, their families are notified but they are not given any travel money. The overseas workers are aware of these risks but are determined to make money. They are completely disillusioned; they know, as I did, that even an egregiously oppressive government has the responsibility to protect its countrymen.

*Translated by Jonathan Corrado