-

IP addresses are NOT logged in this forum so there's no point asking. Please note that this forum is full of homophobes, racists, lunatics, schizophrenics & absolute nut jobs with a smattering of geniuses, Chinese chauvinists, Moderate Muslims and last but not least a couple of "know-it-alls" constantly sprouting their dubious wisdom. If you believe that content generated by unsavory characters might cause you offense PLEASE LEAVE NOW! Sammyboy Admin and Staff are not responsible for your hurt feelings should you choose to read any of the content here. The OTHER forum is HERE so please stop asking.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Ida says mumbai university is a "reputable" university

- Thread starter makapaaa

- Start date

- Joined

- May 9, 2011

- Messages

- 1,987

- Points

- 0

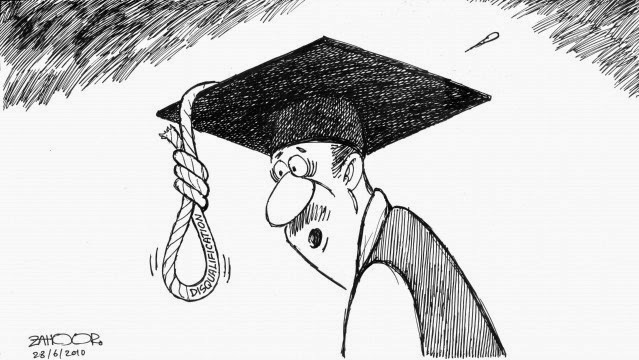

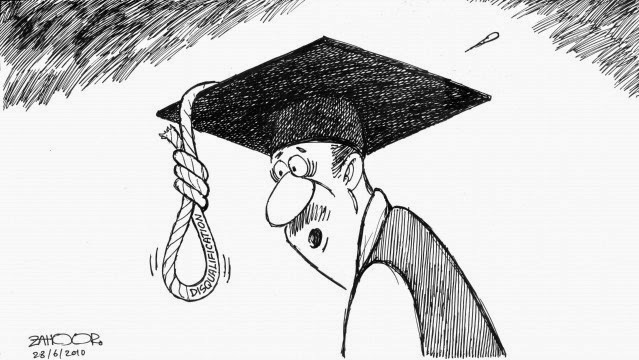

WHY JOB CHEATS CHEAT

When it was pointed out to the Infocomm Development Authority of Singapore that one of its employees, Nisha Padmanabhan, had a Masters degree from a degree mill that has since shut down, the IDA’s response could scarcely have been predicted. It replied that the MBA qualification had little bearing on her hiring. Her salary and job scope were based on her Bachelor’s degree and prior work experience.

Surely, the MBA must have made Padmanabhan stand out from other applicants who only had a Bachelor’s degree. Perhaps the IDA did not want to look a gift horse in the mouth when it hired Padmanabhan in 2014 as it was getting an over-qualified employee without having to pay market value.

In its statement, IDA prides itself in using holistic criteria in employing its staff. Integrity, however, is conspicuous in its absence from its list. Although the IDA announced that it was satisfied that Padmanabhan’s Bachelor’s degree was from a reputable university, it carefully avoided mentioning which university that was. It appears her Bachelor of Engineering degree is from University of Mumbai, which does not appear in the rankings of the top 500 universities in the world. Any local graduate would have received their degree from a more reputable university, yet she was hired.

Curiously, however, it appears important enough for IDA to state that Padmanabhan is a Singaporean. Was IDA trying to allay the accusation that they hired a cheap foreigner over a local?

From Padmanabhan’s LinkedIn profile, it seems she may not have been a Singaporean for very long. Her primary and secondary education as well as tertiary education was in India. She seems to have started working in Singapore in 2005 around the time she bought her MBA degree from Southern Pacific University. Feeling fortunate to have secured employment in Singapore, she may have felt having an MBA would offer her security particularly if she was going to apply for permanent residency and citizenship.

The Workforce Development Agency and Immigrations & Checkpoints Authority, which would have been responsible for scrutinizing Padmanabhan’s qualifications while processing work permit, permanent residency, and citizenship applications, have remained very silent about Padmanabhan. When these agencies successfully prosecute offendors, they rarely fail to announce with some bravado the strict penalties for lying on applications. They will be well aware that Padmanabhan has committed an offence if she had declared her MBA qualifications when she made these applications.

It seems obvious to all except IDA, WDA, and ICA that they have been hoodwinked, caught with their pants down.

IDA states, in its defense:

“We would like to share that Nisha has been a committed team member and contributed in her role as an Applications Consultant for the past year.”

This is entirely believable. Padmanabhan, feeling fortunate to have secured her job, would have kept her head down, worked hard and done what is necessary to keep her position in these uncertain times. Such employees are greatly valued by managers because they are highly compliant and are unlikely to ask hard questions for fear of losing their lucrative job.

From IDA’s viewpoint, it may now seem a shame to fire a perfectly acclimatised and productive employee. What may have been an issue at the time of employment is no longer an issue now since Padmanabhan is clearly able to do the job.

And, this is the reason why many—particularly those from developing countries where well-remunerated jobs are extremely competitive—are tempted to cheat and lie to secure a job. Their primary concern at the time they are applying for their job is to get their foot in the door. They are hopeful that once on board, they will learn the skills needed on the job. With enough time, soon the lies will fade away. This is a well-proven method of laundering one’s academic and professional credentials.

This is why Padmanabhan maintains a LinkedIn profile and why she brazenly lists her MBA degree from Southern Pacific University quite prominently. If a large, high-profile employer such as IDA considers her qualifications favourably, then future employers are unlikely to scrutinize them.

Another reason why this practice is more prevalent in Singapore as opposed to Australia, which is also a highly desirable place for workers from developing countries, is the relatively low chances of getting caught here due to weak detection methods and enforcement. In Padmanabhan’s case, the risk seems to have paid off for her since IDA is taking the inexplicable step of defending her hire.

This will be an encouragement to other foreigners—do what it takes to get the job, then work hard till the degree no longer matters.

But, it will be discouraging for Singaporeans brought up believing in meritocracy.

In Singapore, the onus is placed on the applicant and the employer to be truthful. There are penalties for lying but that, obviously, is only if one is caught. Even then, one could hope for an employer like IDA.

In Australia, the onus is on the authorities to ensure work passes and resident visas are only given to legitimate applicants. The government outsources the screening and verification of qualifications and skills to agencies such as VETASSESS, which more rigorously scrutinize credentials and are also highly accountable to the public. A skills assessment application can take several months and costs around $1000, which is borne by the applicant. Despite the steep cost, it is hardly a deterrent for those wishing to work and live in Australia. The VETASSESS certificate is then provided to the government which uses it to assess work permit and visa applications.

In Australia, employers are wary of cheats from developing countries and use other methods to detect frauds. They will not accept mobile numbers or personal email addresses of referees in resumes. Office numbers are required to verify that they speaking to an actual former employer as it is not uncommon for people from these applicants’ communities to cover for them by providing false testimonies of their experience and qualifications.

It is also not uncommon for ethnic communities to collude in perpetuating such scams. This is easily evident when almost every one vouching for the applicant is of the same ethnicity despite the applicant having worked in multicultural environments. The fibs are viewed as insignificant white lies necessary in enabling people of their own kind to get ahead in what is perceived as an overwhelmingly unfair environment.

The take away from IDA’s statement for the thousands of PMETs from developing countries currently working in Singapore and the many more aspiring to work here is that cheating about your qualifications is fair game when applying for a job as long as you prove yourself afterwards. With time, the lie won’t matter.

The IDA needs to be mindful of the unintended message from its defense of itself and Padmanabhan. Its actions and words perpetuate a common fraud.

The Government too should know that Singaporeans are concerned with the alarming frequency with which foreigners are able to game the system here. Chinese national, Yang Yin is but one high-profile example. He was even able to ingratiate himself enough to get his MP, Dr Intan Azura Mokhtar, to write an appeal letter in support of his permanent residency visa. It is hard to imagine Dr Mokhtar’s letter did not make a difference to his application.

Once the foreign applicants obtain what they want, the fake credentials they provided are effectively laundered. In time, the documents will be forgotten and will no longer matter because the Singapore Government, no less, has legitimized them.

Masked Crusader

*The writer blogs at http://maskedcrusader.blogspot.sg/2015/04/why-job-cheats-cheat.html

When it was pointed out to the Infocomm Development Authority of Singapore that one of its employees, Nisha Padmanabhan, had a Masters degree from a degree mill that has since shut down, the IDA’s response could scarcely have been predicted. It replied that the MBA qualification had little bearing on her hiring. Her salary and job scope were based on her Bachelor’s degree and prior work experience.

Surely, the MBA must have made Padmanabhan stand out from other applicants who only had a Bachelor’s degree. Perhaps the IDA did not want to look a gift horse in the mouth when it hired Padmanabhan in 2014 as it was getting an over-qualified employee without having to pay market value.

In its statement, IDA prides itself in using holistic criteria in employing its staff. Integrity, however, is conspicuous in its absence from its list. Although the IDA announced that it was satisfied that Padmanabhan’s Bachelor’s degree was from a reputable university, it carefully avoided mentioning which university that was. It appears her Bachelor of Engineering degree is from University of Mumbai, which does not appear in the rankings of the top 500 universities in the world. Any local graduate would have received their degree from a more reputable university, yet she was hired.

Curiously, however, it appears important enough for IDA to state that Padmanabhan is a Singaporean. Was IDA trying to allay the accusation that they hired a cheap foreigner over a local?

From Padmanabhan’s LinkedIn profile, it seems she may not have been a Singaporean for very long. Her primary and secondary education as well as tertiary education was in India. She seems to have started working in Singapore in 2005 around the time she bought her MBA degree from Southern Pacific University. Feeling fortunate to have secured employment in Singapore, she may have felt having an MBA would offer her security particularly if she was going to apply for permanent residency and citizenship.

The Workforce Development Agency and Immigrations & Checkpoints Authority, which would have been responsible for scrutinizing Padmanabhan’s qualifications while processing work permit, permanent residency, and citizenship applications, have remained very silent about Padmanabhan. When these agencies successfully prosecute offendors, they rarely fail to announce with some bravado the strict penalties for lying on applications. They will be well aware that Padmanabhan has committed an offence if she had declared her MBA qualifications when she made these applications.

It seems obvious to all except IDA, WDA, and ICA that they have been hoodwinked, caught with their pants down.

IDA states, in its defense:

“We would like to share that Nisha has been a committed team member and contributed in her role as an Applications Consultant for the past year.”

This is entirely believable. Padmanabhan, feeling fortunate to have secured her job, would have kept her head down, worked hard and done what is necessary to keep her position in these uncertain times. Such employees are greatly valued by managers because they are highly compliant and are unlikely to ask hard questions for fear of losing their lucrative job.

From IDA’s viewpoint, it may now seem a shame to fire a perfectly acclimatised and productive employee. What may have been an issue at the time of employment is no longer an issue now since Padmanabhan is clearly able to do the job.

And, this is the reason why many—particularly those from developing countries where well-remunerated jobs are extremely competitive—are tempted to cheat and lie to secure a job. Their primary concern at the time they are applying for their job is to get their foot in the door. They are hopeful that once on board, they will learn the skills needed on the job. With enough time, soon the lies will fade away. This is a well-proven method of laundering one’s academic and professional credentials.

This is why Padmanabhan maintains a LinkedIn profile and why she brazenly lists her MBA degree from Southern Pacific University quite prominently. If a large, high-profile employer such as IDA considers her qualifications favourably, then future employers are unlikely to scrutinize them.

Another reason why this practice is more prevalent in Singapore as opposed to Australia, which is also a highly desirable place for workers from developing countries, is the relatively low chances of getting caught here due to weak detection methods and enforcement. In Padmanabhan’s case, the risk seems to have paid off for her since IDA is taking the inexplicable step of defending her hire.

This will be an encouragement to other foreigners—do what it takes to get the job, then work hard till the degree no longer matters.

But, it will be discouraging for Singaporeans brought up believing in meritocracy.

In Singapore, the onus is placed on the applicant and the employer to be truthful. There are penalties for lying but that, obviously, is only if one is caught. Even then, one could hope for an employer like IDA.

In Australia, the onus is on the authorities to ensure work passes and resident visas are only given to legitimate applicants. The government outsources the screening and verification of qualifications and skills to agencies such as VETASSESS, which more rigorously scrutinize credentials and are also highly accountable to the public. A skills assessment application can take several months and costs around $1000, which is borne by the applicant. Despite the steep cost, it is hardly a deterrent for those wishing to work and live in Australia. The VETASSESS certificate is then provided to the government which uses it to assess work permit and visa applications.

In Australia, employers are wary of cheats from developing countries and use other methods to detect frauds. They will not accept mobile numbers or personal email addresses of referees in resumes. Office numbers are required to verify that they speaking to an actual former employer as it is not uncommon for people from these applicants’ communities to cover for them by providing false testimonies of their experience and qualifications.

It is also not uncommon for ethnic communities to collude in perpetuating such scams. This is easily evident when almost every one vouching for the applicant is of the same ethnicity despite the applicant having worked in multicultural environments. The fibs are viewed as insignificant white lies necessary in enabling people of their own kind to get ahead in what is perceived as an overwhelmingly unfair environment.

The take away from IDA’s statement for the thousands of PMETs from developing countries currently working in Singapore and the many more aspiring to work here is that cheating about your qualifications is fair game when applying for a job as long as you prove yourself afterwards. With time, the lie won’t matter.

The IDA needs to be mindful of the unintended message from its defense of itself and Padmanabhan. Its actions and words perpetuate a common fraud.

The Government too should know that Singaporeans are concerned with the alarming frequency with which foreigners are able to game the system here. Chinese national, Yang Yin is but one high-profile example. He was even able to ingratiate himself enough to get his MP, Dr Intan Azura Mokhtar, to write an appeal letter in support of his permanent residency visa. It is hard to imagine Dr Mokhtar’s letter did not make a difference to his application.

Once the foreign applicants obtain what they want, the fake credentials they provided are effectively laundered. In time, the documents will be forgotten and will no longer matter because the Singapore Government, no less, has legitimized them.

Masked Crusader

*The writer blogs at http://maskedcrusader.blogspot.sg/2015/04/why-job-cheats-cheat.html

- Joined

- May 9, 2011

- Messages

- 1,987

- Points

- 0

IDA EVADES NETIZEN’S QUESTIONS ON MEXICAN FT CONSULTANT

TAV had been notified by Lovecraft RavenEye that IDA has just replied to her queries over the employment of Alan Ramos, the Mexican IT Consultant hired by IDA, and who was charged for having had kinky sex with a 15 year old minor.

Some of the questions posed to IDA were:

1. How was his psychology degree from Harvard able to land him the IT job?

2. What was it that had helped him capture the job with no previous work experience whatsoever?

3. How was it that local applicants who had graduated from NUS/NTU and other universities with bachelors in IT, with CITPM and PMP certificates; and who have as many as 10 years of SDLC project under their belts – were not selected?

4. What superb skills does Alan Ramos possess?

IDA’s reply seems to totally disregard the questions posed to them. Instead, they took the opportunity to proclaim how strict they are and how they had “immediately suspended” him. Furthermore, they are quick to disassociate themselves with Ramos, saying he is no longer an employee of IDA.

What is even more laughable is the proud declaration that “IDA maintains a high standard of personal and professional conduct”.

If this is true, then IDA must not evade the questions posed to them by Lovecraft RavenEye.

Which part of the “high standard of personal and professional conduct” had made them see fit to employ a fresh school graduate over those with far wider and vast experiences?

What is it in the professional conduct that makes them disregard and avoid the questions posed to them?

Why are they, in their professional conduct, sending a reply which no one outside the PAP is interested to know?

We are beginning to feel that we are made of glass.

The Alternative View

[source]: https://www.facebook.com/pages/The-Alternative-View/358759327518739

TAV had been notified by Lovecraft RavenEye that IDA has just replied to her queries over the employment of Alan Ramos, the Mexican IT Consultant hired by IDA, and who was charged for having had kinky sex with a 15 year old minor.

Some of the questions posed to IDA were:

1. How was his psychology degree from Harvard able to land him the IT job?

2. What was it that had helped him capture the job with no previous work experience whatsoever?

3. How was it that local applicants who had graduated from NUS/NTU and other universities with bachelors in IT, with CITPM and PMP certificates; and who have as many as 10 years of SDLC project under their belts – were not selected?

4. What superb skills does Alan Ramos possess?

IDA’s reply seems to totally disregard the questions posed to them. Instead, they took the opportunity to proclaim how strict they are and how they had “immediately suspended” him. Furthermore, they are quick to disassociate themselves with Ramos, saying he is no longer an employee of IDA.

What is even more laughable is the proud declaration that “IDA maintains a high standard of personal and professional conduct”.

If this is true, then IDA must not evade the questions posed to them by Lovecraft RavenEye.

Which part of the “high standard of personal and professional conduct” had made them see fit to employ a fresh school graduate over those with far wider and vast experiences?

What is it in the professional conduct that makes them disregard and avoid the questions posed to them?

Why are they, in their professional conduct, sending a reply which no one outside the PAP is interested to know?

We are beginning to feel that we are made of glass.

The Alternative View

[source]: https://www.facebook.com/pages/The-Alternative-View/358759327518739

- Joined

- May 9, 2011

- Messages

- 1,987

- Points

- 0

Lelong! Why Study for a Masters When Fake Degrees Can Do the Trick?

This guy came to me and offered me his name card. My God, was I impressed. Below his name is a long list of credentials. Let me just list them down to show you how well qualified he is.

B. Eng, Masters Computer Science,

Ph D Eng,

Ph D Science,

Ph D Social Engineering,

Ph D Technology.

I asked him if he was in senior management. He said no, just an engineer. But his boss was very impressed and even asked him how to get these Ph Ds to add on to his name card. He said his boss only got a B Eng from NUS. Now his boss felt malu looking at his name card.

I said soon he should be taking over his boss position. He said no lah. He was employed only because of his first degree which was genuine and from a reputable university in Geylang, the rest he bought it from the degree mills. Oh, you mean degree mills degrees can also be printed in the name card. He assured me can. He said he listed them in his CVs also. But not to worry, the rest just for show show only. The boss knew he did not get them by the normal and proper academic route. But it is okay. No worry, no crime. Not a crime.

This is the new fashion in Singapore. Even one government agency did not find any problem with it, till now. He said if don’t believe go and ask IDA. This type of thing is very normal one. If I don’t have a long list, employers would say I got no relevant skills set compare to FTs. FTs all got very long list of degrees and many many skills set.

I was so happy that I too went to get a few Ph Ds to add onto my name card. My name card now is printed on two sides. Too many degrees from University of Cempedak, University of Tekka, University of Telok Blangah, University of ….Oops, I can’t remember, so many of them that I don’t even know what they are. But shiok, damn shiok. Damn impressive. Whenever I meet anyone I will hand them my name card. Lan par oso song.

This story was written by Chua Chin Leng and first published on My Singapore News.

Send us your stories ay [email protected]

This guy came to me and offered me his name card. My God, was I impressed. Below his name is a long list of credentials. Let me just list them down to show you how well qualified he is.

B. Eng, Masters Computer Science,

Ph D Eng,

Ph D Science,

Ph D Social Engineering,

Ph D Technology.

I asked him if he was in senior management. He said no, just an engineer. But his boss was very impressed and even asked him how to get these Ph Ds to add on to his name card. He said his boss only got a B Eng from NUS. Now his boss felt malu looking at his name card.

I said soon he should be taking over his boss position. He said no lah. He was employed only because of his first degree which was genuine and from a reputable university in Geylang, the rest he bought it from the degree mills. Oh, you mean degree mills degrees can also be printed in the name card. He assured me can. He said he listed them in his CVs also. But not to worry, the rest just for show show only. The boss knew he did not get them by the normal and proper academic route. But it is okay. No worry, no crime. Not a crime.

This is the new fashion in Singapore. Even one government agency did not find any problem with it, till now. He said if don’t believe go and ask IDA. This type of thing is very normal one. If I don’t have a long list, employers would say I got no relevant skills set compare to FTs. FTs all got very long list of degrees and many many skills set.

I was so happy that I too went to get a few Ph Ds to add onto my name card. My name card now is printed on two sides. Too many degrees from University of Cempedak, University of Tekka, University of Telok Blangah, University of ….Oops, I can’t remember, so many of them that I don’t even know what they are. But shiok, damn shiok. Damn impressive. Whenever I meet anyone I will hand them my name card. Lan par oso song.

This story was written by Chua Chin Leng and first published on My Singapore News.

Send us your stories ay [email protected]

IDA is missing the whole point as is many stupid sinkies. At issue is not the reputation of Mumbai University or any of those shit universities. Its just a smoke screen. The real issue is the integrity of this bitch. That she would obtain a fake degree from a paper mill (I doubt if she even set foot on the campus or had to take any online course work), speaks to the unethicalness of this bitch. She knowingly and deliberately bought a fake degree to embellish her meagre qualifications. How can you trust this cunt? IDA looks like a fool for not doing their checks on this university. If she lied about this what else did she lie about? Is her work performance also lies? And to be given a singapore PR for this shit? Really sinkie PR like toilet paper now adays for apunehs to wipe their backside.

I agree with you 100%. IDA is a regulatory agency and should have set a MUCH higher standard. Even if the person was hired based on her first degree, her ethical standards are suspect due to this fake degree and she should not remain employed AT a regulatory agency. By allowing her to continue sets a tone at the top and puts a stain on the reputation of the IDA.

I am also surprised that we are hiring foreigner governmental agencies. In many countries such jobs are reserved for citizens.

HR should also check into the validity of her Mumbai University degree.

- Joined

- Jul 25, 2008

- Messages

- 63,240

- Points

- 113

I agree with you 100%. IDA is a regulatory agency and should have set a MUCH higher standard. Even if the person was hired based on her first degree, her ethical standards are suspect due to this fake degree and she should not remain employed AT a regulatory agency. By allowing her to continue sets a tone at the top and puts a stain on the reputation of the IDA.

I am also surprised that we are hiring foreigner governmental agencies. In many countries such jobs are reserved for citizens.

HR should also check into the validity of her Mumbai University degree.

is ida synonymous with indian degree advocacy and approval?

- Joined

- Aug 10, 2008

- Messages

- 110,786

- Points

- 113

If IDA cannot find Singaporeans degree holders, hiring a Diploma holder from local polytechnics is better than someone with degree from University of Mumbai.

They can find, but their wages too high.

Also, there are fake diplomas and fake certificates.

- Joined

- Aug 10, 2008

- Messages

- 110,786

- Points

- 113

I agree with you 100%. IDA is a regulatory agency and should have set a MUCH higher standard. Even if the person was hired based on her first degree, her ethical standards are suspect due to this fake degree and she should not remain employed AT a regulatory agency. By allowing her to continue sets a tone at the top and puts a stain on the reputation of the IDA.

I am also surprised that we are hiring foreigner governmental agencies. In many countries such jobs are reserved for citizens.

HR should also check into the validity of her Mumbai University degree.

That's the problem: who regulates the regulators? We already have a corrupt CPIB. Who watches the watchmen?

- Joined

- Jul 19, 2011

- Messages

- 28,269

- Points

- 113

is ida synonymous with indian degree advocacy and approval?

Good one, Mr Shit!

- Joined

- Nov 24, 2008

- Messages

- 24,474

- Points

- 113

IDA = Indians Dubious Academics

Definitely agreed. Their graduates can give you the answer of 1 plus 1 faster than you can say eleven.

[h=1]IDA SAYS MUMBAI UNIVERSITY IS A "REPUTABLE" UNIVERSITY[/h]

Post date:

17 Apr 2015 - 11:43am

The Infocomm Development Authority of Singapore (IDA) has come out to further defend one of their staff who has a degree from a known degree mill.

Nisha Padmanabhan was previously an Indian national who has become a Singaporean citizen. She has a degree from the Southern Pacific University.

The university was previously closed down in Hawaii because it was facing several lawsuits and was criticised for its shoddy business practices.

However, IDA is now insisting that Ms Nisha is from a "reputable" university and is distancing itself from the Southern Pacific University.

"We have investigated and would like to share that Nisha Padmanabhan, a Singapore citizen who joined IDA in 2014, has a Bachelor’s degree from a reputable university and was recruited because of this Bachelor degree, extensive past work experience and good track record," IDA said.

The "reputable" university in question is the University of Mumbai where she obtained a Bachelor’s degree in Electronics and Telecommunication.

However, the Mumbai University is not ranked in the top 500 in both the QS World University Rankings and the Times Higher Education Top 400 World University Rankings 2014-2015.

IDA then tried to distance itself from the Southern Pacific University and said that it did not take that into consideration for her employment.

"Nisha pursued an MBA out of personal interest, and it was not a relevant certificate for her position in IDA though she was open about the fact that she had obtained it," IDA added.

"Her MBA from Southern Pacific University was not a factor that contributed to her employment at IDA. In fact, 93.5% of all IDA staff that were hired at the level of Applications Consultant were based on their Bachelor’s degree.

It would appear to be weird that in trying to defend her, IDA would first claim that they ignore her other qualifications and also tried to bring out the statistics that in their hiring, they also only consider the Bachelor’s degrees of their those who were hired and not their other qualifications.

That then begs the question - does IDA not look at the integrity of their candidates in their hiring. If any of their workers were hired if they were do undergo unethical methods to obtain a degree, this should be questionable, whether or not the IDA's decision to hire them is only based on some qualifications?

- Joined

- Jul 5, 2012

- Messages

- 161

- Points

- 28

Definitely agreed. Their graduates can give you the answer of 1 plus 1 faster than you can say eleven.

Hello, one plus one can also be Chinese character "Wang". In between black and white, there is also a grey area.

- Joined

- Jun 20, 2011

- Messages

- 4,732

- Points

- 83

is ida synonymous with indian degree advocacy and approval?

Should be indian Dung Affiliation.

- Joined

- Jun 21, 2010

- Messages

- 35,968

- Points

- 113

Curtin Uni is rank 331??? N to think singkies pay full fees to study there,,,,and heaps of singkies in spore lose out to an ah neh from ah neh uni? singkieland is really the dumps

During my time Curtin was not even a uni.....it was machiam a poly where singkies who got no where to go after a levels went to study there to while away the time. That was what it was famous for

- Joined

- Jul 17, 2011

- Messages

- 10,331

- Points

- 0

The funny thing about this whole IDA saga,,is Singkie students who have no A levels and went overseas to study be it in curtin etc,,will never be able to get work in the spore civil service etc as got no A levels etc and never go through the PAPpee approved route,,,unofficially if got overseas degree and no A levels,,,the serpents will only class u as 'O' levels if u have one,,that is why its better for an overseas graduate to remain overseas,,,,and now an ah neh from 3rd world education etc can get a job with the gahmen??? thanks 60%.,..

During my time Curtin was not even a uni.....it was machiam a poly where singkies who got no where to go after a levels went to study there to while away the time. That was what it was famous for

Each time IDA sought to put forward their reasoning for hiring Nisha, IDA would inevitable end up digging an even deeper hole.

By coming out to proclaim that University of Mumbai is reputable and it's the only reason Nisha was hired (by IDA), the issue has mutated into something bigger. If IDA had admitted its mistake and fired Nisha immediately, the issue would have remained with one person (Nisha), one University (SPU), one Government Department (IDA).

By coming out to proclaim that University of Mumbai is reputable and it's the only reason Nisha was hired (by IDA), the issue has mutated into something bigger. If IDA had admitted its mistake and fired Nisha immediately, the issue would have remained with one person (Nisha), one University (SPU), one Government Department (IDA).

What's wrong with this farking country ? Why so many Govt Depts,Stat Boards,TLCs and GLCs staffed with Foreigner Workers? All experienced and qualified Singaporean Workers all dead already ?

KNNCCB to MIW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

KNNCCB to MIW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Similar threads

- Replies

- 7

- Views

- 686

- Replies

- 21

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 12

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 2

- Views

- 275

- Replies

- 14

- Views

- 2K