Time’s ripe to revamp COE system, start charging more for road use, say panellists at ST roundtable

Five out of six panellists felt the time was ripe to review and change the system, given that the technology to control usage has matured. ST PHOTO: KUA CHEE SIONG

Esther Loi

DEC 11, 2023

SINGAPORE - The certificate of entitlement (COE) system should be revamped with more emphasis on controlling the usage of vehicles on the road, instead of simply capping their numbers, said panellists at a roundtable organised by The Straits Times.

Five out of six panellists felt the time was ripe to review and change the system, given that the technology to control usage has matured and Singapore is rolling out its

next-generation electronic road pricing (ERP) system, which is satellite-based and capable of charging motorists based on distance travelled.

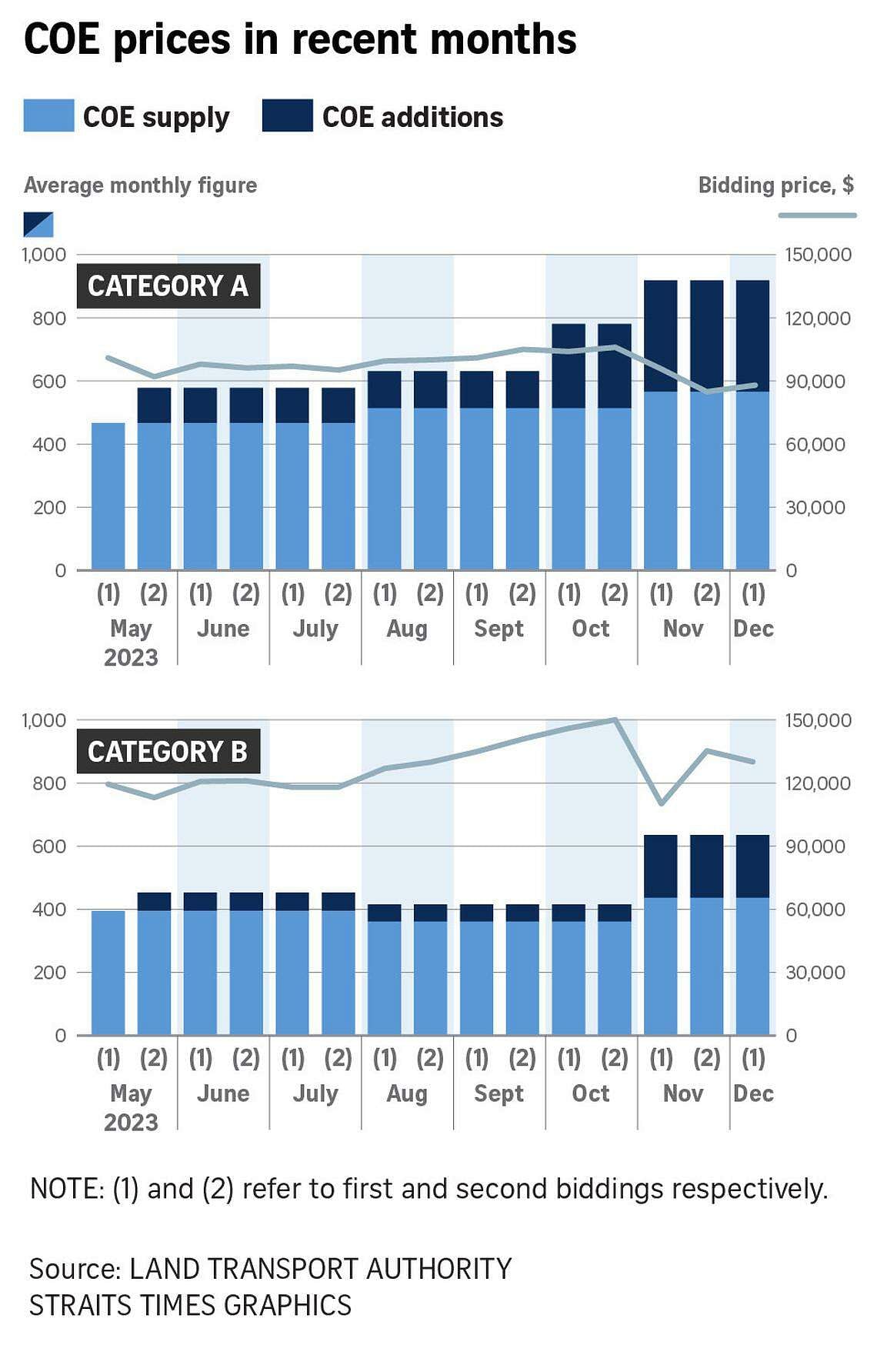

ST hosted the roundtable on Nov 23 to discuss whether the COE system merely requires tweaks or a major overhaul, in the wake of surging premiums in 2023 with records being set in the larger car and Open categories

for six consecutive tender exercises from August to October.

After reaching highs of $150,001 (Category B) and $158,004 (Open), premiums

fell across all categories at the first tender in November after the Government brought forward more COEs from future peak-supply years to raise supply.

Economist Ivan Png, who is Distinguished Professor at the National University of Singapore, said it was time for the Government to “take a big step” and roll out distance-based charging for road usage, which will also indirectly charge for carbon emissions.

The unhappiness over the existing COE system, coupled with a comprehensive MRT network and introduction of satellite ERP, provides an opportunity for change, he added.

“This is the moment to make a big reform, and then put us into a private transport system that will carry us forward for the next couple of decades.”

Others on the roundtable were Associate Professor Walter Theseira, who heads the urban transportation programme at the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS); Dr Victor Kwan, previously a senior motor trader and now senior lecturer with SUSS; automotive consultant and former motor trade veteran Say Kwee Neng; co-founder and chief executive of used-car marketplace Carro Aaron Tan; and ST’s senior transport correspondent Christopher Tan.

Tackling usage to control congestion

Mr Aaron Tan questioned why the COE supply is being crimped by the current zero-growth vehicle policy.

“We’ve been building roads, tunnels and expressways over the last few decades. Our population is increasing too, so why is the COE quota being held constant?” he said in response to ST’s senior transport correspondent Lee Nian Tjoe, who moderated the roundtable.

Mr Christopher Tan said a zero population growth rate for cars was “draconian”.

Prof Png added: “If we’re worried about the problem of emissions from power stations, so we do something about switching from coal to natural gas, or from natural gas to solar energy – that is a natural solution to address the problem.

“We wouldn’t limit the number of power stations.”

Agreeing that more should be done to tackle car usage, Mr Christopher Tan said: “Right now, it’s a total imbalance. So much weight has been put on the ownership-acquisition part and very little on the actual usage... The actual usage is actually what causes congestion, which is what the COE system is trying to tackle in the first place.”

The panellists noted that high COE prices may prompt drivers to use their cars more, which worsens congestion.

Prof Png cited a study he had conducted, which found that motorists who bought their cars between 2008 and 2010 – when COE premiums were low – used their cars less than those who paid high premiums in 2012. “We interpret this as a psychological effect. I spent so much money on this thing so, oh, I should use it.”

Mr Christopher Tan noted that there are no usage-based controls to prevent drivers from using their cars, especially with the abundance of parking spots and well-connected road networks.

“So where’s the usage deterrent? There’s none, practically, for someone who spent $200,000 on a car,” he said.

The proper pricing of road usage would encourage more drivers to switch to using public transport, Prof Png said.

“If you let people own a car, but you make it more expensive to use, they’re going to be happy in a different way. They enjoy that they have the option.

“But now... the choice is too one-sided: I’ve spent a ton of money on the car, and then I pay almost nothing to use it, especially if I have a fuel-efficient car or an electric vehicle. So, of course, I use the car,” he added.

Mr Say believes that having a fixed number of vehicles on the road is not the only cause of high COE prices, citing usage and other factors driving demand such as easy access to loans.

“Because when you have a limited supply of anything, the price eventually is driven by demand,” he said, adding that there has to be a way to “neuter easy access” to financing, citing past examples where the Government intervened on this front and effectively cooled COE prices.

On reforming the existing system, he said: “It boils down to political will to do the right thing.”

Prof Theseira noted that when the Government was justifying the roll-out of ERP in the past, “they were very clear that with better use of electronic road pricing, they could actually see a way to let more Singaporeans own cars because the problem of congestion and cost of car ownership could be controlled much more effectively through road pricing, rather than just upfront charges”.

While there may be unhappiness on the ground if distance-based charging is rolled out, he said: “Since we’re already unhappy with COE, why not say, look, let’s just relook everything and accept that the alternative might be more efficient from an economic perspective, and also maybe not be that much more painful from the psychological perspective either.”

Reducing volatility

Prof Theseira said the high COE premiums and price volatility are “symptoms of a system that isn’t working as well as it should”.

Dr Kwan describes the current price volatility of COEs as a “feast or famine” situation arising from the 10-year COE cycle.

The switch from a forecast system – which estimated the number of available COEs based on the forecast number of deregistered vehicles every year – in 1999 to one based on actual deregistration figures in 2010 led to a sudden plunge in COE quotas, as most of the existing cars were still new and not undergoing deregistration.

In turn, this pushed up COE prices dramatically, Dr Kwan said.

Prof Theseira noted that the COE quotas originated from vehicle stock numbers in the 1990s, which may be outdated. He asserted that these figures were not determined by any research or scientific mechanisms either.

Unlike the other panellists, Dr Kwan feels the COE system is “not broken” and requires only tweaks.

He believes the fundamental demand-supply system can “sort itself out” with minor adjustments such as charging more for usage and increasing the supply vis-a-vis Singapore’s population growth.

With more COEs from future peak-supply years being brought forward to fill the present supply troughs through

the Government’s “cut and fill” approach, ST’s Mr Tan noted that this will be a gradual process of flattening the disruptive feast-and-famine COE supply cycle.

He noted that from 2015 to 2021, there were about 100,000 five-year COE renewals for vehicles that would need to be scrapped once they reached the end of their statutory lifespans.

It is “better late than never” to bring these 100,000 COEs earlier into the market, since the increase in supply effectively brought about a fall in COE prices across the board earlier in November, he added.

He hopes that COE prices will continue to stabilise, though he cautions that it will not be an overnight fix.

Dr Kwan supports this view, adding that the Government is “on the right track” as COE prices will likely stabilise at a reasonable level through this measure.

Prof Theseira said the fixed COE tenure of 10 years creates the problem of perpetuating any present changes or mistakes in the future, when existing COEs lapse 10 years down the road.

He added that policymakers are understandably cautious about further levelling out COE supply across the years.

“Today, lots of people complain about COE prices, but not that many are actually buying a car and facing that high price. But when they come to the bumper years – the next couple of years – when people who own mass-market cars are going to be deregistering them and buying a car, they will be expecting COE prices to be at the level that is consistent with a very large COE supply,” he said.

“So if you were to take their COE from that period and redistribute them to now, all of a sudden, they’re going to find that the prices are not as low as they thought they would be, and then you have a different political problem.”

He called for a return to the drawing board to study if there should be a more flexible system that accurately reflects the costs of driving and congestion.

“In my ideal scenario, you would have a system where it might not be cheap to drive a car in Singapore. I don’t think it ever will be cheap because of our constraints,” Prof Theseira said.

“But at least the price will be somewhat predictable. And it won’t change a huge amount in the month-to-month or year-to-year basis. It will change reflecting underlying supply and demand for using vehicles in Singapore. But it won’t be dramatic, and I think that will be better for everybody.”