MP Tin Pei Ling joins Grab: Conflict of interest or much ado about nothing?

Many MPs from both the ruling party and opposition hold other jobs. So what makes Ms Tin’s case different, and why the public outcry now?

Grace Ho

Deputy News Editor

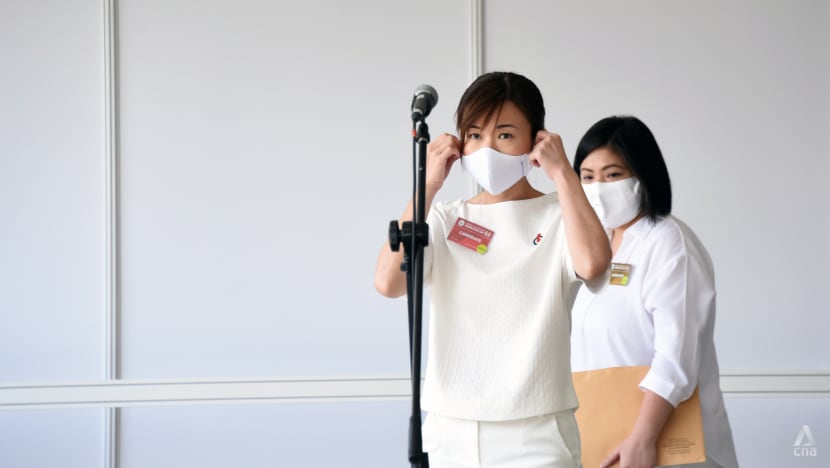

Member of Parliament Tin Pei Ling joins Grab as director of public affairs and policy. PHOTOS: MCI, LIANHE ZAOBAO

FEB 5, 2023

At a time when Singaporeans are wondering how Grab rides became so expensive, last week, they were confronted with another question about the ride-hailing giant: Why was MP

Tin Pei Ling allowed to join Grab as its Singapore director of public affairs and policy?

Is there any conflict of interest between this and her role as a politician?

Bear in mind that most MPs here hold day jobs, and sit on boards and committees.

For example, Sembawang GRC MP Mariam Jaafar is a managing director at the Boston Consulting Group. Bishan-Toa Payoh GRC MP Saktiandi Supaat is an executive vice-president at Maybank Group, and Sengkang GRC Workers’ Party (WP) MP Jamus Lim is an associate professor at Essec Asia-Pacific, just to name a few.

Bukit Panjang MP Liang Eng Hwa is a managing director at DBS Bank, and chairs the Finance and Trade and Industry Government Parliamentary Committee (GPC). West Coast GRC MP Ang Wei Neng is president of Strides Mobility, a subsidiary of transport operator SMRT, and a member of the GPC for Transport.

The issue is not unique to Singapore.

In 2021, attention was drawn to British MPs’ second jobs, when former North Shropshire MP Owen Paterson was found to have had misused his political position to benefit two companies he worked for.

By definition, a conflict of interest means a person has competing interests or loyalties because of his duties to more than one person or organisation.

But there is no actual, potential or apparent conflict of interest simply by being an MP employed in the private sector, Singapore Management University (SMU) associate law professor Eugene Tan told me.

“The issue is more of when a conflict of interest arises… An MP who does not promptly remove himself from (such a) situation does so at his peril,” he said.

Professor Lawrence Loh, director of the Centre for Governance and Sustainability at NUS Business School, said that it is “only when the rubber hits the road” that a specific case can be assessed to determine if there is any concern for conflict.

Ms Tin has not shown any actual conflict of interest. So why the public fuss over her?

Rules of right behaviour

Today, MPs can recuse themselves from a matter if they have concerns about conflicts of interest, or declare upfront their private roles, such as during Parliament debates.

There are also established party rules on how to deal with conflicts of interest, although it is the respective political parties’ prerogative to decide what goes into them.

The WP’s rules of prudence, for example, do not contain a section on the separation of business and politics, unlike the People’s Action Party’s (PAP).

In Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s

letter to PAP MPs on rules of prudence in 2020, PM Lee wrote that MPs who are employed by companies or industry associations may at times have to make public statements on behalf of their company or industry association.

If they have to do so, they must make it clear they are not speaking as an MP, but in their private, professional or business capacity, he said.

“Do not use parliamentary questions or speeches to lobby the Government on behalf of your businesses or clients.”

According to the PAP’s rules of prudence, MPs are allowed to sit on boards of private and publicly listed companies. But they should decline the role if the company is not reputable, or they do not have a meaningful contribution to make.

Section 32 of the Parliament (Privileges, Immunities and Powers) Act 1962 also states: “A Member shall not in or before Parliament or any committee take part in the discussion of any matter in which he has a direct personal pecuniary interest without disclosing the extent of that interest and shall not in any circumstances vote upon any such matter.”

One way to enhance this provision is to require MPs to disclose any potential conflict of interest to the public, said Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS) law lecturer Ben Chester Cheong.

But he acknowledges that it is “impracticable” to get the public to vote on every potential conflict of interest an MP has.

At the end of the day, MPs are elected by and accountable to the public, said Mr Cheong. “A consequence of failing to satisfy the electorate’s concern could be the possibility that one may not be re-elected.”

There seems to be little risk of this happening to Ms Tin.

In 2020, the much-loved politician romped home to electoral victory with 71.74 per cent of the votes in her MacPherson single-member constituency seat, an improvement of over 6 percentage points from her vote share in the 2015 election.

Changing attitudes

But a more deep-seated issue may be that Singaporeans’ attitudes are changing.

Citing the longstanding practice of seconding high-ranking administrative officers in the civil service to work in the private sector, SUSS Associate Professor Walter Theseira said the Government’s strategy has always been to “embrace close coordination” between the state and key industries.

“I expect Ms Tin’s hiring by Grab was seen no differently (by the Government),” he said. “But it doesn’t necessarily look to the public like that is the right way to do things anymore.”

A legitimate concern is whether people are trading on their MP status to get jobs that others cannot, he said, adding that some members of the public may desire a more arms-length relationship between politicians and industry.

Another big concern flagged by SMU’s Prof Tan is that, leveraging her position as MP, Ms Tin could enable her company to have access to decision-makers and information not in the public domain. Could this give her company an advantage over its competitors?

As Prof Tan said, her corporate title has become “the proverbial lightning rod”.

In this instance, a director for public policy is normally responsible for monitoring, reacting to, and – where feasible – providing input on government policy. The nature of Ms Tin’s role may have affected public perception.

But there may be double standards here, given that there seems to be less public outcry over MPs being practising doctors or lawyers.

“One does get the feeling the public is more accepting of some MP jobs than others,” said Prof Theseira, suggesting that some constituents may feel that their MPs can more flexibly manage their affairs with such jobs.

History also plays a part. Former PAP MP and Progress Singapore Party chairman Tan Cheng Bock’s political “legend”, for example, was partly built on him being a rural doctor to poor farmers who paid him in kind with eggs, vegetables and chickens.

In the end, MPs who are professionals across diverse industries can bring different views and perspectives to Parliament, so that policy issues are better represented and debated.

But, as Prof Theseira pointed out, being an MP in a small country like Singapore makes it impossible to be treated anonymously.

The ultimate safeguard is still the MPs’ own conscience and judgment. Hence, on relevant matters, they must declare their interest promptly, and recuse themselves from being further involved.