Covid-19 NZ: Singapore, the country that decided to let Covid in

www.stuff.co.nz

What is it like to go from no Covid to thousands of cases? Keith Lynch explains what’s going on in Singapore and considers the lessons New Zealand can learn.

Imagine a 1pm Covid briefing in mid-December. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern walks out – wearing a mask, of course – and announces some good news: nearly 85 per cent of the country is now fully vaccinated.

Despite that, she insists the ongoing restrictions, which are something akin to Level 2.5, are very much necessary. Finally, she gets to the numbers.

There are about 3500 new infections in the community and 3 new deaths.

READ MORE:

* That most controversial 1pm Covid press conference, explained

* Ireland and Covid-19: More than 1000 cases every day but normality looms

* Ivermectin is not proven as a treatment for Covid-19

How would that make you feel? Well, Singapore – a country that experts agree may offer a glimpse into New Zealand’s future – is grappling with just this.

Of course, it’s not a perfect comparison: Singapore is a dense city state. New Zealand is long and pitted with rural population pockets. The crucial similarity is we have almost no immunity within the population from the disease itself.

On Wednesday last week, Singapore saw 3577 new cases. (

some believe the number of infections may be much higher). Three people died. They were aged between 68 and 102 – all were unvaccinated and had various underlying conditions.

More than 1500 people were in hospital. The country’s Ministry says “most are well and under observation”. About 250 needed oxygen and 37 people were in critical condition in ICU. This sometimes seems to get lost but the data from around the world shows over and over again that

age matters more than anything else when it comes to the severity of Covid. This is reflected in Singapore’s numbers on Wednesday. More than 239 of those very ill people were above 60.

For some context, there are about 15 to 25 empty ICU beds on a normal day in New Zealand, Dr Andrew Stapleton, chair of the College of Intensive Care Medicine, told

Stuff this week.

Singapore’s approach to Covid-19 in many ways mirrored Aotearoa’s. It embraced elimination for a long time until it

decided that it was “no longer possible”.

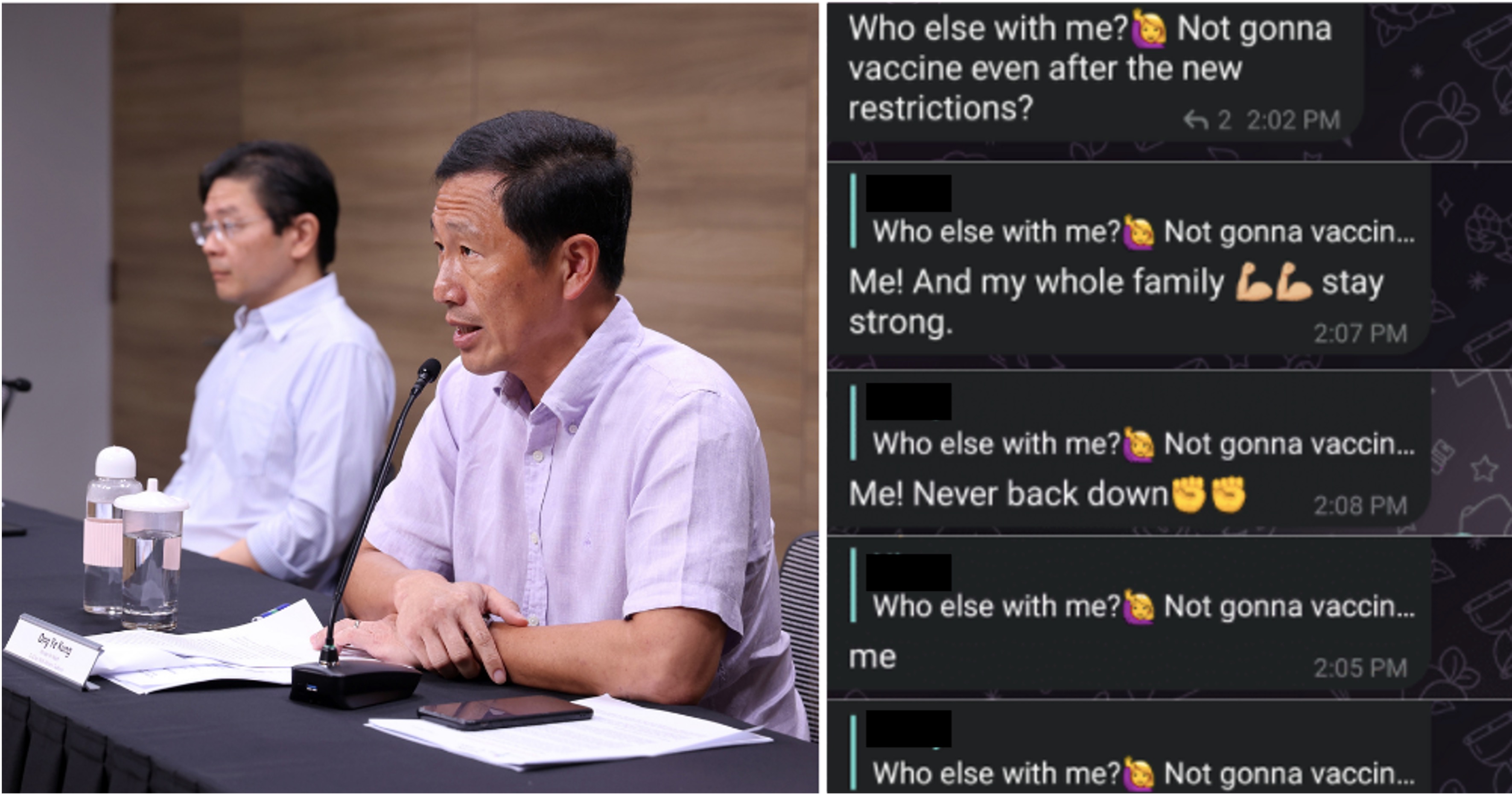

On Saturday, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong expanded on that, saying Delta meant it was not possible to stamp out Covid-19 with lockdowns and safe management measures (SMMs).

Singaporeans must change their mindset over the virus, he said, according to

The Straits Times.

"Let us go about our daily activities as normally as possible, taking necessary precautions and complying with SMMs. With vaccinations, Covid-19 has become a treatable, mild disease for most of us.”

In August there were more than 100 cases daily in the island nation of about 5.5 million people.

Singapore got to choose the terms of its surrender. More than 80 per cent of the entire country was fully vaccinated. (If New Zealand – at its current vaccine rates – saw Singapore’s case numbers the costs would be heavy.)

There was no version of the UK’s

“Freedom Day”, though. This was a staged careful retreat. Small groups of people were allowed to, for example, dine in restaurants and border restrictions were eased a touch for fully vaccinated people.

But as we now know

Delta is a different beast. Its sheer speed and infectiousness have meant cases have skyrocketed. The vaccines significantly reduce the risk of infection, yet they are not perfect. It may be that people simply encounter the virus so often that eventually it breaks through.

Singapore has now reintroduced a range of restrictions to dampen down the virus’ spread. For example only two fully vaccinated people can dine out together. Businesses are mostly open, but there are significant limitations. You can read the full list

here. It’s probably akin to level 2 or level 2.5, even.

Singapore is now in the middle of what’s called its exit wave,

Adam Kucharski, an infectious-disease modeller at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine told

Stuff.

This, he says, is what New Zealand should expect if it follows a similar path.

“Although high vaccination coverage on its own could have stopped transmission for the original variant or the

Alpha variant, there is reduced effectiveness against infection for Delta, and further waning of this effectiveness over time. This means that even if countries were to vaccinate 100 per cent of their population with current vaccines, it wouldn’t necessarily be enough to stop transmission of Delta if all control measures were lifted.”

Delta was in Singapore in August, but

as Professor Dale Fisher, senior consultant at Singapore’s National University Hospital (NUH) Division of Infectious Diseases, told me it was “waiting to be released”. Just a few more personal interactions was enough to foster exponential growth. And remember there are probably pockets of unvaccinated people.

That said – and this sounds very much counterintuitive – some public health experts say allowing Covid in now is not necessarily a bad thing. For the vaccinated “infection will not have any short-term or long-term consequence for their health, but may additionally trigger a natural immune response which reduces the chance of subsequent infection”, Teo Yik-Ying, dean of the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health at the National University of Singapore told

CNBC.

So has it been manageable?

- Over the last 28 days (as of Wednesday) 98.3 per cent of the more than 42,000 infections were asymptomatic or mild.

- 590 people needed oxygen or to be admitted to ICU.

- 71 people have died (equating to a 0.2 per cent death rate) and 69 per cent of those were unvaccinated/partially vaccinated. (Yes, you might say 30 per cent were fully vaccinated, but remember the vast majority of people are vaccinated. This snapshot illustrates once again Covid is now very much a disease of the unvaccinated.)

So, what happens when elimination really ends?

Well, Singapore is still in a state of flux. Some people are understandably scared. Throughout 2020 and 2021, as Fisher told me, the message from the government was we must stop Covid and contain it at all costs.

This probably sounds familiar to New Zealanders.

And then it changed. The message was, he says: “We’re going to take our foot off the brakes. We’re going to let it infiltrate the community, and it’s no longer as deadly a disease [after mass vaccination]. It’s much safer.

More from

Keith Lynch • Explainer editor

[email protected]

“And when the numbers skyrocketed, it looked like the government was failing. But in fact, it was an expected increase, because we were removing the restrictions.”

The daily numbers, in particular, are terrifying to many, causing widespread fear and anxiety. As Fisher tells me the majority of people being admitted to hospital did not need to be there. Some did not want to go home in case they infected a household member – they were understandably scared.

This is why Fisher and some other health professionals believe

Singapore should stop counting or at least publicising case numbers. (Not all health professionals agree on this, of course).

Right now, every household in Singapore is

given their own testing-kits. Mass testing means finding a lot of asymptomatic cases. There’s also confusion around whether vaccinated people with mild Covid should

recover at home – which is meant to be the default – or go elsewhere.

The rationale for stopping mass testing and subsequently releasing daily case numbers is simple: Case numbers aren’t necessarily important. They were collected as Singapore wanted

no Covid – when authorities found the virus they acted. Now they’re not trying for no cases. Singapore introduced policies that were always going to drive numbers up; the wave was inevitable. What matters now is ensuring the number of hospitalisations and deaths is managed.

The Pfizer vaccine is effective regardless of your ethnicity

Read more

Jeremy Lim, of the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, wrote online that the emergency departments have been overwhelmed by people with mild or no symptoms. He believes the testing should be focused on protecting those most at risk of severe Covid along with their close contacts.

What now?

The first question is: should this all have happened in the first place? Fisher’s opinion is clear:

elimination or zero-Covid was simply not feasible in the long-term.

Yes, zero-Covid is better than Covid. The problem is that zero-Covid is not viable once the borders open up.

Delta is too infectious, it moves too quickly and the vaccines are not perfect.

The vast majority of the world has accepted the virus. This left Singapore with no options, really.

Singapore is now enduring what

Australian epidemiologist Tony Blakely describes as a “bumpy exit” to join the rest of the world. The good news is that their bump should be much less severe. They have mass vaccination. They understand how Covid spreads and treatments are emerging.

That said, every expert I spoke to for this piece agrees with one thing – it simply cannot be a case of just throwing the country wide open. The retreat has to be staged, done in a way that protects the vulnerable and stops hospitals being overwhelmed.

For Singapore, this means ongoing restrictions. It also means pursuing a kind of granular or scaled-down

elimination strategy laser focused on keeping Covid out of rest-homes and hospitals.

“You have to accept the community can’t be zero-Covid, but you really want your nursing homes and hospitals to be zero-Covid,” Fisher says.

This is not easy. Those places are not islands – people move in and out – but through a combination of targeted rapid testing of healthcare workers and masking they hope to reduce the impact on those most susceptible to the virus. Singapore is also administering

booster shots to its elderly residents.

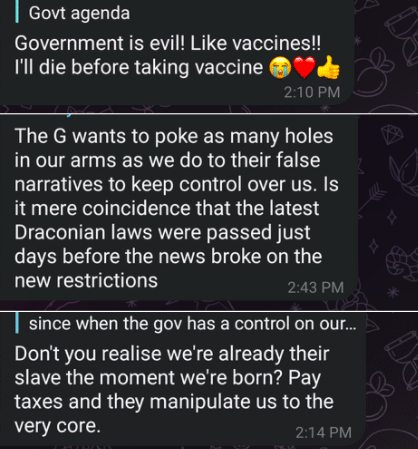

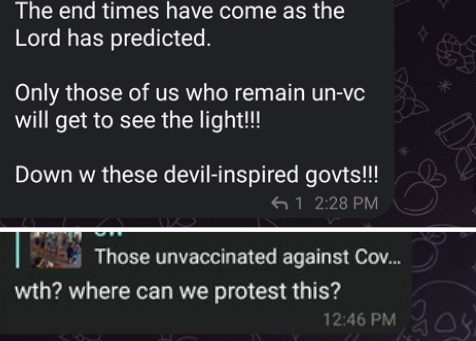

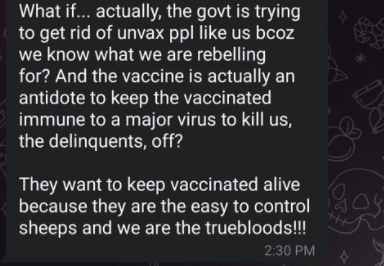

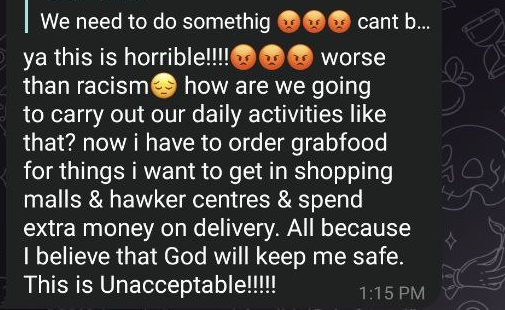

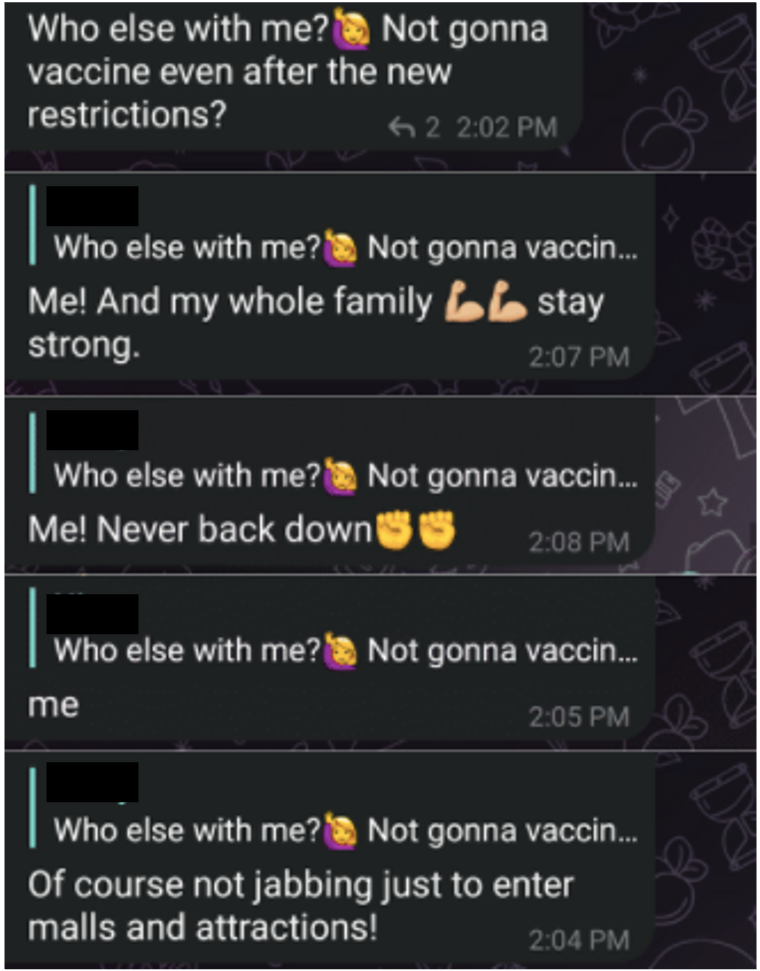

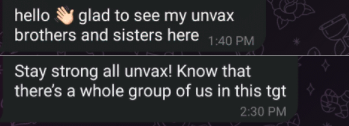

It’s also worth remembering that while Singapore’s vaccination rate is high, there’s still about 500,000 who have not been jabbed. That’s a lot, and they can still threaten the health system.

“We find that about half the people who need hospitalisation are vaccinated and the other half are unvaccinated. So that, but you've got to bear in mind that there's 10 times as many vaccinated people, so they are hugely protected,” Fisher says.

He believes, broadly speaking, that the population is coming to terms with the new reality. It’s not easy though. Some conservatives want a

‘Freedom Day’. Some want the borders to shut and lockdowns to return.

According to a

Financial Times report that cited market research, about a quarter of people thought the restrictions were too strict, a quarter said they needed to be tougher – but half thought they were fine.

“The day New Zealand hits 1000 [cases] I’m sure there’ll be a shock across the nation. How did we let this happen.” But it’s inevitable some day, Fisher says. “It’s a highly contagious disease.”

New Zealand’s Covid-19 Catch 22

I recently wrote about

Ireland, a country of 5 million people. Its current restrictions are less strict than Singapore, but it’s only seeing about 1000 cases daily. Its remaining restrictions

will be lifted next month.

The big difference between Ireland and Singapore (and by extension New Zealand) is

what Prof Shaun Hendy calls “banked immunity”.

“The advantage that Europe has over us at the moment is that a large proportion of its young adults will have some immunity from infection, which means that all things being equal,

their R number (the average number of people one person passes the virus on to) will be lower than ours,” he says.

In a recent letter to government Auckland epidemiologist Prof Rod Jackson took a similar tone: “Covid-19 is likely to have already immunised a significant proportion of the ‘hard to reach’ groups in most western European countries, so vaccination rates in European populations do not reflect their current levels of immunity, particularly in the most vulnerable groups.”

He puts it like this – these are the people hard to reach for the vaccine but easy to reach for the virus.

For example in the UK, it’s thought more than 90 per cent of the adults would have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in the week starting August 23. This suggests those people have had Covid-19 or been vaccinated.

Across the

entire UK, there’s been a steady increase in the number of people in younger, typically more mobile, age groups testing positive for antibodies.

So essentially what these numbers tell us is that the UK’s vaccination rate doesn’t accurately reflect the number of people with some sort of immunity from the virus.

In New Zealand only 4500 people have actually had Covid-19, a tiny pool that doesn’t contribute to our collective immunity.

Stopping the virus – or at least suppressing it – until a vast majority of the population is vaccinated was clearly a right call. But this in itself has created a Catch 22, of sorts.

“The UK has about 94 per cent of adults with immunological evidence of either vaccination or natural infection,” Blakely says. “So their total population immunity is higher than what we (both New Zealand and Australia) have.”

Even now in the UK – which is technically fully open – social interactions are not like they were in 2019. It’s a little like a self-imposed alert level for a lot of people.

So at the moment, Kucharski, says it’s likely a “combination of immunity and residual caution that’s been keeping cases reasonably flat”.

What this means for New Zealand is that we need even higher vaccination rates than our friends in Europe and even then

some restrictions are probably necessary.

What can we learn from Singapore?

At the moment Singapore is coping, the case numbers were essentially expected, and some believe the case numbers and deaths should peak before the end of the year, and start coming down.

What next depends on the hospitals, really. According to a recent report in

The Straits Times (ST), occupancy in intensive care was up from 26 per cent to 53 per cent.

Singapore’s Ministry of Health has also taken some extraordinary steps – even building new community facilities to prop up hospitals. These are for people who are OK but have underlying conditions.

There's also the debate as to what cost Singapore was willing to accept. In a recent discussion held by ST, Singapore public health Professor Hsu Li Yang made the point that currently two people a day die of flu in the country. If it wanted to open up faster, Singapore needed to accept six to seven deaths a day. That equates to about 2300 deaths in a year. Is that acceptable?

I asked the Singapore experts what message they would offer to New Zealand authorities.

Fisher's message is frank. “You’ve managed to avoid it [Covid] so far but reckoning day has to happen. That will require what looks like backtracking or giving up ground.”

He says that transition can certainly not be a ‘Freedom Day’. It has to be slow-moving, it has to be cautious, it’s about monitoring the health services, it’s about considering where the

most vulnerable are – and keeping Covid away from them.

Lim says: “If New Zealand wants to avoid the messy situation Singapore is in currently, please do keep it simple.”

But, he says, we need to accept that some people will die.

That said some epidemiologists believe we shouldn’t necessarily let the virus in even with very high vaccination. Blakely points out that if we knew even

better vaccines were on the horizon (that are more effective at stopping spread, for example), aggressively suppressing the virus in New Zealand (in a way that’s socially acceptable) may be worth considering. It also may be Delta simply makes this impossible.

No matter the route we take, the takeaway is sobering and simple. High vaccination rates and restrictions will help protect us but normality does not loom.

Prof Hsu made this point: “New Zealand is in a good place not just because case numbers and deaths from Covid-19 have been low, but because there are many countries ahead of it that are re-opening (or have re-opened). You can observe and learn from all the mistakes and successes of those ahead of you, including Singapore.”

/figure1_10oct2021.png?sfvrsn=c690e5b3_0)

/figure2_10oct2021.png?sfvrsn=7c92f745_0)

/figure3_10oct2021.png?sfvrsn=746b35f7_0)

/figure5_10oct2021.png?sfvrsn=be54e399_0)

/figure6_10oct2021.png?sfvrsn=97dc4818_0)