- Joined

- Jul 25, 2008

- Messages

- 12,469

- Points

- 113

Militants' success in Afghanistan will be a threat for South-east Asia sooner or later

A Taleban fighter with local residents of Pul-e-Khumri after the Afghan city was seized by the group on Wednesday.PHOTO: AFP

Raul Dancel and Linda Yulisman

Aug 14, 2021

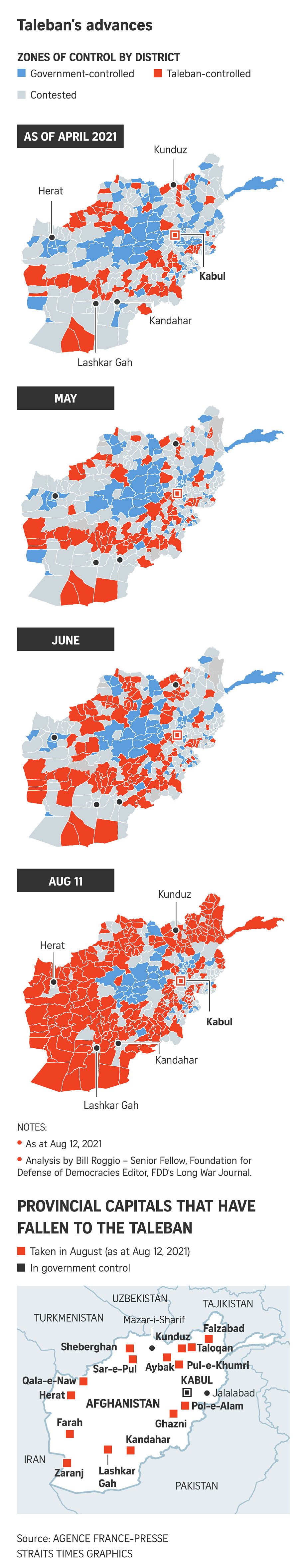

MANILA/JAKARTA - In days or weeks, Afghanistan's capital Kabul is expected to fall. The Taleban would have by then completed its stunning advance to seize control of the entire country, even before the United States officially ends its military mission there on Sept 11.

By Friday (Aug 13), the militant group had captured Kandahar in the southern Pashtun heartland, the second- largest city in the country, as well as Herat, a cultural and economic hub and the third-largest city. The city of Pol-e-Alam fell later in the day.

Only three major cities - including capital Kabul - remained under government control, and two of them were under siege from the Taleban.

Some American officials fear the Afghan government will implode within 30 days, and are preparing for an evacuation of the US Embassy in Kabul.

If Afghanistan once again comes under full Taleban rule, what will this mean for South-east Asia?

Analysts say there is no immediate threat to the region, especially as most parts of the world are in lockdown or under some form of movement restrictions and border controls because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

"There's no immediate risk of Taleban victories strengthening extremists in South-east Asia," said Ms Sidney Jones, a senior adviser at the Jakarta-based Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict.

For now, Afghanistan is just a massive propaganda victory for the Taleban. No doubt, one message will resonate with Muslim militants around the world, and that is: In a war of attrition, the Americans will always walk away.

"The Taleban won, like in Vietnam... What the US spent 20 years building is crumbling in mere weeks," said Mr Lucio Pitlo III, a research fellow at the Asia-Pacific Pathways to Progress Foundation.

But, in a year or two, South-east Asia will have more than just breast-beating zealots to deal with.

A Taleban-ruled Afghanistan will be a showcase of the radical form of Islam that will reel in idealists and imams all over the world, eager to gain combat experience or some form of military and religious training that they can bring back home.

Fighters and resources will inevitably flow from Afghanistan, landing in some remote jungle on the southern Philippine island of Sulu, or a densely populated district in Jakarta or Kuala Lumpur.

Enclaves in northern Afghanistan that form part of a vast, ancient territory known as Khorasan, "the blessed land", are seen gaining even more prominence in the war on terror.

Khorasan, which also spans Iran and Turkmenistan, is where militants believe an army will rise that will deliver the fatal blow to "infidels".

Militants recruited by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) from South-east Asia have been reported to have holed up there after fleeing Syria. They sneaked in via Iran, hoping to find a "family-friendly", purely Islamic state.

Analysts believe that with the Taleban back in power, Khorasan could be the next destination for militant fighters.

"It's not impossible that there will be a call for jihad in Khorasan resembling those in Afghanistan in the 1980s, Mindanao in the 1990s, and recently in Syria," said Mr Adhe Bakti, an analyst from the Centre for Radicalism and Deradicalisation Studies, in Jakarta.

That, however, will not be happening any time soon.

There are nuances to the dynamics at work between the Taleban and those supporting ISIS and its precursor, Al-Qaeda. Those who are pro-ISIS, for one thing, are anti-Taleban.

"So, there is not a great likelihood that Taleban victories will lead to a new rush of South-east Asians to join ISIS," said Ms Jones.

She noted that the Taleban's allies in South-east Asia, meanwhile, have either been decimated or have moved on.

Indonesian security forces have been rounding up members of Jemaah Islamiah (JI) since mid-2019, totally eviscerating the organisation.

In December last year, the Indonesian police nabbed an Afghan-trained militant who was believed to have led the elite squad involved in the suicide bombing at Jakarta's JW Marriott hotel that killed 12 people in 2003 and made bombs that killed 202 people in Bali a year earlier. The police also uncovered a JI training site in Central Java.

These efforts minimise the risk of strengthening extremism in Indonesia in the short term, despite the Taleban's stronger foothold in Afghanistan, said Indonesia's national counterterrorism agency chief Boy Rafli Amar.

Said Ms Jones: "(JI) will grow back, but it will take some time."

In the Philippines, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) is now engaged in running its own autonomous region as part of a peace deal it brokered with the government.

Many of the group's battle-hardened commanders had trained in camps along the Afghan border. "But now the MILF has no time for terrorism," said Ms Jones.

In Malaysia, continuing turmoil on the political scene may, for now at least, be drawing militants' gaze inward "instead of a worrying situation that develops elsewhere in this disconnected world", said Mr Muhammad Sinatra, a foreign policy analyst with the Institute of Strategic and International Studies Malaysia.

"It is too soon to project whether the Taleban's advancement would energise radical and violent extremist groups here," he said.

Once the Taleban succeeds in retaking the Afghan capital, it will likely muddle through the years, trying to consolidate its hold on the country and fighting off rivals.

Eventually, militants will be heeding the call again once the threat of the pandemic recedes and border controls are eased in two to three years.

In the interim, terror groups such as JI could, for instance, roll out Afghanistan-centred propaganda to target those cooped up in their homes and stuck to their phones and computers because of the pandemic.

Mr Pitlo said that while pandemic-related border controls may prevent militants from sneaking into and out of Afghanistan, money could still flow freely to give extremist groups in South-east Asia, which have fallen on hard times because of the pandemic, a lifeline.

For South-east Asia's security planners, it is never too early to be prepared to deal with a renewed threat.

- Additional reporting by Hazlin Hassan in Kuala Lumpur