Money laundering case: Some suspects donated six-figure sums to charities

Some of the charities have ringfenced the money, while others lodged police reports and plan to surrender the cash to the police. PHOTOS: LIANHE ZAOBAO FILE, ST FILE

Andrew Wong and

Samuel Devaraj

Oct 8, 2023

SINGAPORE - At least five of the 10 accused in the

$2.8 billion money laundering case have allegedly donated to various charitable organisations and social service agencies in the past three years.

This includes at least $52,000 to Rainbow Centre, the operator of three special education schools, and at least $15,000 to the National Kidney Foundation (NKF), checks by The Sunday Times showed.

Lions Befrienders, a social service agency that serves the elderly, said it received $5,000 from one of the men in 2022.

In Parliament on Tuesday, Second Minister for Home Affairs Josephine Teo said in

her ministerial statement that some of those arrested had made donations to charities here.

Some of the charities have ring-fenced the money, while others lodged police reports and plan to surrender the cash to the police.

ST asked 10 charities and non-profit organisations if they had received donations from any of the 10 accused in the case.

According to Rainbow Centre’s annual report, it received between $30,000 and $99,999 from a Wang Shuiming in 2022.

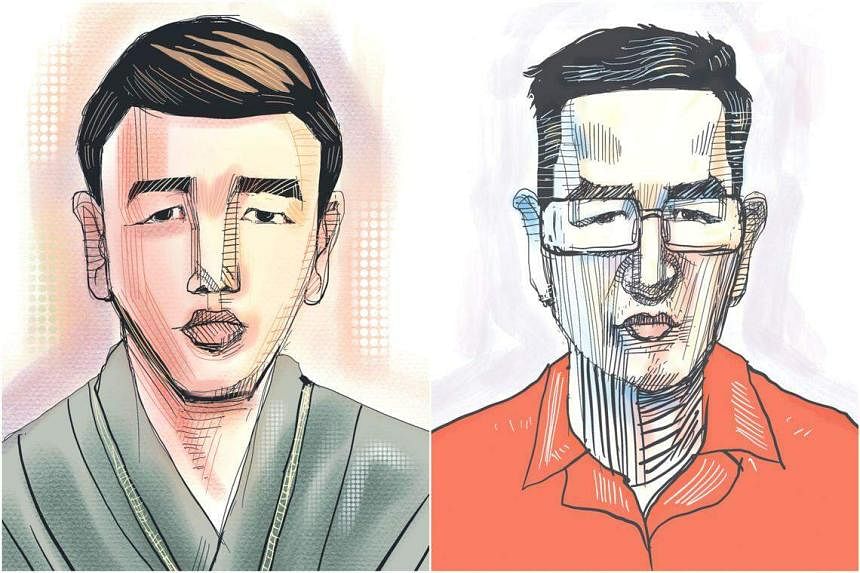

Turkish national Vang Shuiming, 42, who is also known as Wang Shuiming, faces five charges: one for using a forged document and four for money laundering.

The documents from Rainbow Centre also show that a Su Haijin had donated between $3,000 and $9,999 each year between 2021 and 2023, while a Zhang Ruijin donated between $10,000 and $29,999 in 2021, and between $3,000 and $9,999 in 2022.

Cypriot national Su Haijin, 40, faces

one charge of money laundering and another for resisting arrest.

Chinese national Zhang Ruijin, 44, faces a total of three forgery charges.

A Su Baolin appeared in NKF’s annual reports from 2020 to 2022, in a list of people who donated at least $5,000 annually to the organisation.

Cambodian national Su Baolin, 41, faces two forgery charges.

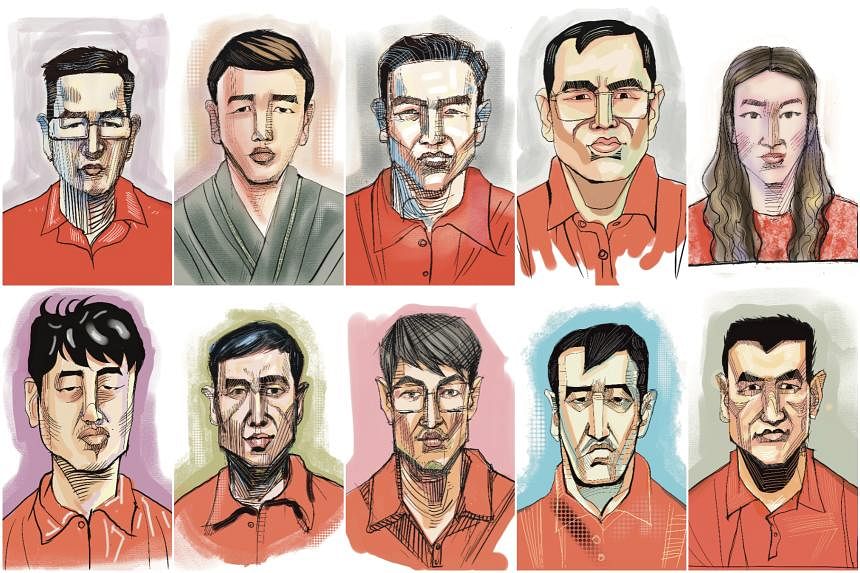

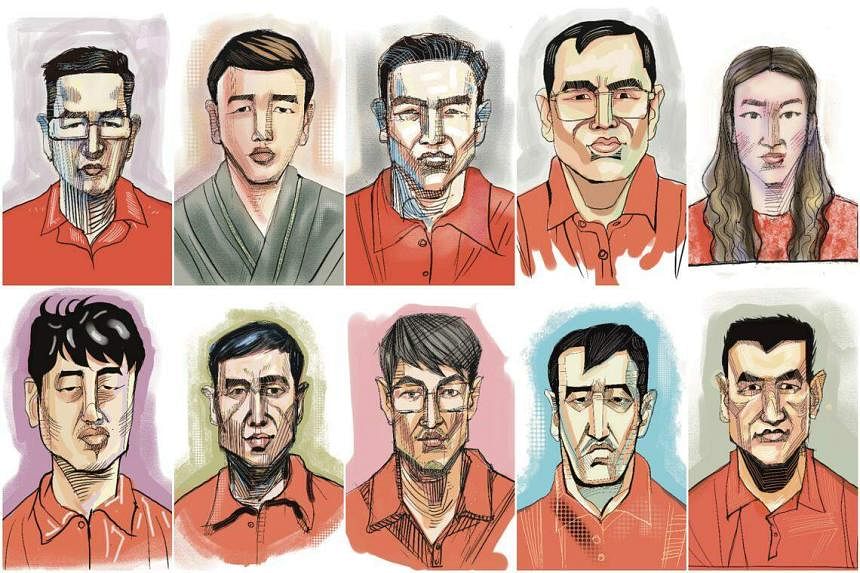

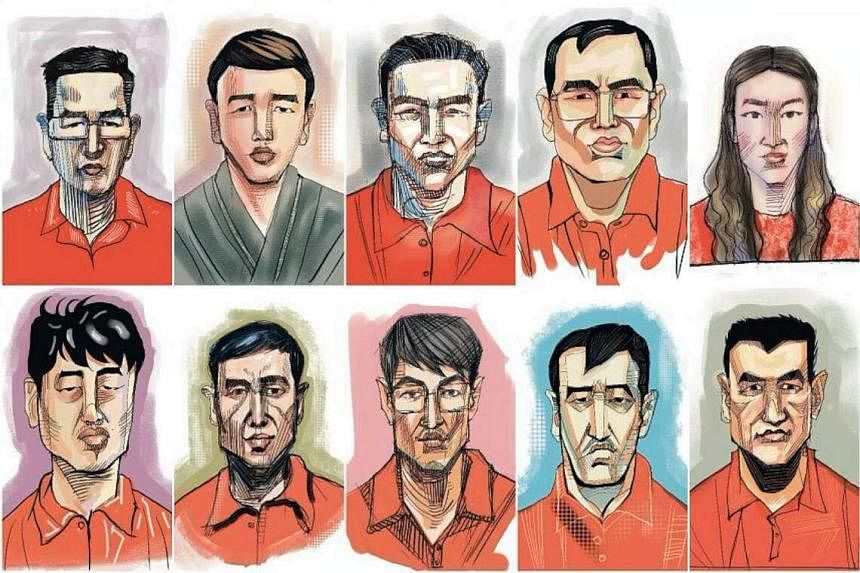

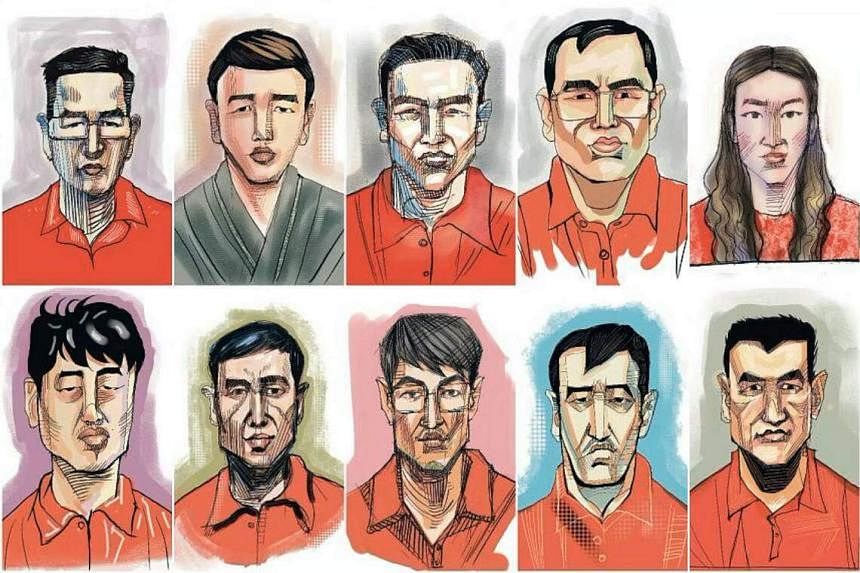

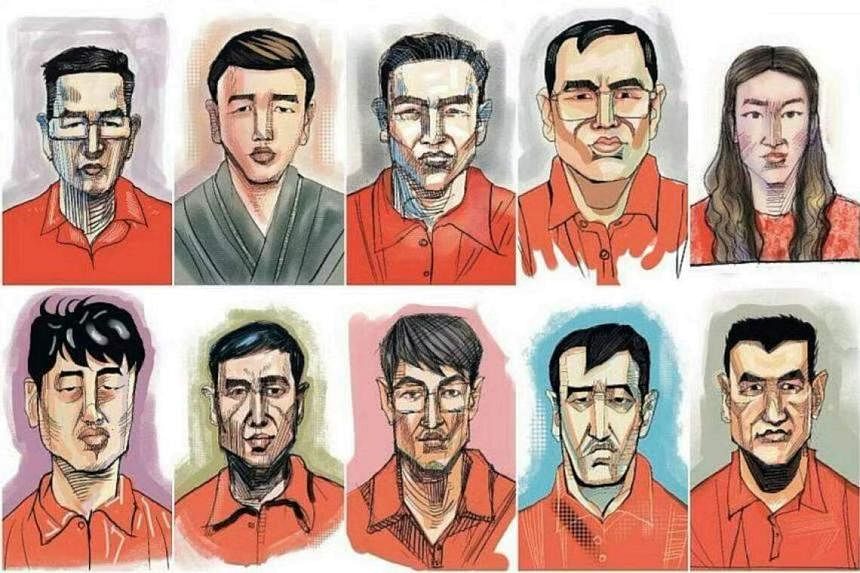

The 10 accused are (clockwise from top left) Su Baolin, Su Haijin, Chen Qingyuan, Su Wenqiang, Lin Baoying, Zhang Ruijin, Wang Dehai, Su Jianfeng, Vang Shuiming and Wang Baosen. ST ILLUSTRATIONS: CEL GULAPA

An NKF spokeswoman said the charity could not confirm if it was the same Su Baolin involved in the case, and did not say if it was aware of any donations made by anyone linked to the money laundering case.

She said NKF has a policy of due diligence checks on its donations, to provide beneficiaries with “reasonable assurance” that the donation did not come from any illegal source.

“In instances where there are concerns about the ethical implications of a potential or suspicious donation, a decision will be made to decline the donation following the due diligence check,” she said, adding that the relevant authorities would be notified, if necessary.

Rainbow Centre did not reply by press time.

Lions Befrienders executive director Karen Wee said it received a $5,000 donation in 2022 from one of the 10, but declined to reveal the person’s name.

Ms Wee said: “Even though the amount of money was small compared to the $2.1 million we raised in 2022-2023, we made a police report because Lions Befrienders is about transparency and accountability.

“We will return the money if we have to.”

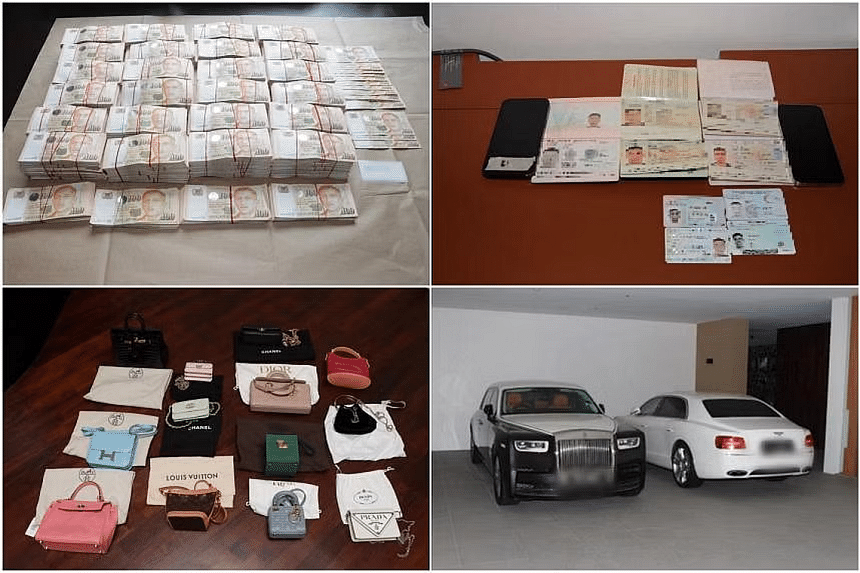

On Aug 15, more than 400 officers led by the Commercial Affairs Department

raided locations including Tanglin, Bukit Timah, Orchard Road, Sentosa and River Valley.

Nine men and one woman, originally from China, were charged the next day with offences including money laundering, forgery and resisting arrest.

It is

Singapore’s worst money laundering case and one of the world’s largest.

There were earlier media reports of Sian Chay Medical Institution receiving donations from some of the accused.

On Aug 24, the social service agency told ST the amounts included a cheque of $100,000 each from Su Haijin, Su Baolin and Zhang Ruijin in 2020, which were then given to the President’s Challenge.

Sian Chay’s spokesman added that from 2020 to 2022, Su Haijin donated an additional $101,000 in total to the organisation.

Su Baolin donated an additional $39,000 from 2021 to 2023 in total, while Zhang Ruijin donated an additional $12,000 in 2021.

On Aug 30, Zhang Ruijin’s defence lawyer, in arguing for his client to be granted bail, said in court he had been active in doing charity work, and had donated to local charities.

On Tuesday, Mrs Teo said the Commissioner of Charities will be issuing an advisory to encourage all charities to review donor records to check if they have received donations from the 10 accused or entities that are related to them.

Charities that find irregularities must file suspicious transaction reports (STRs), she added.

Under the Corruption, Drug Trafficking and Other Serious Crimes (Confiscation of Benefits) Act, individuals or organisations must file an STR if they know or reasonably suspect that a property – in this case, a cash donation – may be linked to serious crimes, including money laundering.

An individual who fails to do so may be fined up to $250,000 or jailed for up to three years, while an organisation can be fined up to $500,000.

Ms Victoria Ting, associate director at Setia Law, said whether a charity organisation can be taken to task depends on whether it should have reasonably suspected the source of donations could be tainted.

The former deputy public prosecutor, who specialised in white-collar crime, said red flags include a mismatch between the donor and donation.

She said: “For example, when a donation in the name of a company is wired from a personal account, or an unusually large donation is received which does not seem commensurate with the donor’s known background or income.”

Another red flag, she said, is when a large donation is “smurfed” – a tactic money launderers use to split up transfers into multiple smaller amounts, which suggests an intention to avoid triggering reporting requirements.

But the task could be daunting for charities that may not be equipped to handle such checks.

Lions Befriender’s Ms Wee said: “We have multiple sources of donations and a large volume of donors, and it is difficult to do in-depth checks on each of them.”

She said that for organisations like hers, typically only large amounts above $10,000 would trigger greater scrutiny.

This includes verification checks to ensure the donation is not from someone blacklisted by the police or who has a dubious background or businesses.

The organisation has limited methods to conduct background checks on potential donors. Ms Wee said checks can be done with the credit bureau, but this will work only if the businesses or individuals are operating in Singapore.

Otherwise, she said, they rely on public announcements or police updates on potential offenders.

“Ultimately, what kinds of checks charities do and which donors we check on is a judgment call that we need to make based on the limited resources we have,” she added.

Meanwhile, Ms Ting said money launderers donate to charities for several reasons.

She said: “Where the charity is legitimate, it could be to lower their taxable income, to obtain goodwill and standing in the community, or even just to acquire good karma.

“On the other hand, where charities can also be entirely controlled by a criminal group, then it could operate as a front to receive and transmit illicit payments akin to any other shell company.”

ST reported on Sept 18 that some Chinese businessmen had tried to offer money in the form of donations, in exchange for honorary titles in clan associations.

Mr Or Teck Seng, general secretary of the Singapore Ann Kway Association, said: “From my understanding, this is to show they are assimilating into society, which is one of the prerequisites of either becoming a Singapore citizen or getting permanent resident status.”

Lawyer Chenthil Kumarasingam, a partner at Withers KhattarWong, said some criminals may use charity organisations to hide their ill-gotten gains.

“Essentially, the idea is to pass the funds through the charity’s bank accounts and then access them later, whether through corruption in the charity or setting up sham charities to accept the funds from a directed donation,” he said.