-

IP addresses are NOT logged in this forum so there's no point asking. Please note that this forum is full of homophobes, racists, lunatics, schizophrenics & absolute nut jobs with a smattering of geniuses, Chinese chauvinists, Moderate Muslims and last but not least a couple of "know-it-alls" constantly sprouting their dubious wisdom. If you believe that content generated by unsavory characters might cause you offense PLEASE LEAVE NOW! Sammyboy Admin and Staff are not responsible for your hurt feelings should you choose to read any of the content here. The OTHER forum is HERE so please stop asking.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Prometheus ! Greatest disappointment this year

- Thread starter singveld

- Start date

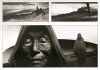

The photo above is taken from the prologue of ‘Prometheus,’ in which one of the extraterrestrial Engineers sacrifices himself in order to allow his DNA to plant the seeds of life on Earth. But we bet you didn’t know that someone is standing right behind him — someone not seen in the finished film.

Even before ‘Prometheus’ was released, rumors about a director’s cut by Ridley Scott and deleted footage began floating around the Intertubes. Now that the movie is out, fans are even hungrier for such material to help explain the movie’s mysteries (God knows we could use the help).

Prometheus Forum has uncovered one such goodie in the photo below, which shows an alien referred to as an “Elder Engineer” standing behind the Engineer we already know, just before the latter drinks his lethal drink and allows his genetic material to unravel in the waters of Earth (the site also has a batch of interesting behind-the-scenes and on-set pictures of the actors transforming into aliens).

Played by Matthew Rook, the “Elder Engineer” is definitely not seen in the theatrical version of the movie. Is he there as some sort of priest to give spiritual and moral strength to the Engineer who’s about to sacrifice his own life? Or is he on hand to give the guy a good, solid push just in case he starts to chicken out?

Hopefully we’ll get those answers on the ‘Prometheus’ Blu-ray — that is, if a version of the scene featuring the “Elder Engineer” makes it to the disc. Until then, chalk this photo up as yet another of the many elements of the film that Scott and screenwriter Damon Lindelof prefer to leave as an enigma…at least until the sequel gets greenlit.

Prometheus – Movie Review

So does Prometheus live up to the hype? Our new writer Imogen Reed investigates . . .

Ever since Prometheus was announced, fans have been driving themselves crazy with rumors and speculation. Everyone wanted to know more. Everyone wanted to see this. Years in the making, Ridley Scott’s dramatic return to the Alien franchise was bound to be an explosive one. Thankfully, the long wait is finally over and Prometheus has hit the cinema screens. But is it all it’s cracked up to be?

At first glance, it looks phenomenal. The trailer had fans worked into a frenzy before they set foot in the cinemas and the opening scenes were dramatic, mysterious and utterly tantalizing.

It’s a science-fiction film that seems to have it all – stunning special effects, brilliant actors and sets that just blow you away. The look and feel of Prometheus is entirely new and veers into the realms of ‘modern’ and ‘futuristic’ as opposed to the more grungy look of Alien. Even the ship’s interior is ultra-modern in its design – no hardwood coffee tables or sectional sofas here. But there is a distinct flavor of the Nostromo from the original films. The airlocks and corridors have that similar claustrophobic shape (albeit with a much more sleek appearance) and even the ships signage harks back to that old retro-futuristic font styling. It’s a similar feel throughout the film – something brand new with a familiar touch. Even down to the storyline.

So… is this a prequel or not?

I won’t go into the plot but whatever you’ve been told, do not believe the hype. There’s been numerous tall-tales going around that Prometheus isn’t an Alien film or that it’s only very remotely related. Some have even suggested that it’s simply ‘in the same universe’ as the originals. Even Ridley Scott himself has said in an interview that only “by the end of the third act you start to realize there’s a DNA of the very first Alien”. Unfortunately, somebody’s been telling porky-pies.

It’s true that there are differences – Prometheus is set a good thirty years before the events of Alien and it doesn’t tie in directly. For example, many believed that this film would explain the Space Jockey’s presence on LV-426, the planet where Ripley first encounters the Alien creature. That turned out not to be the case, but we are shown more of the Space Jockey’s race (referred to as The Engineers in Prometheus) and it essentially delves into the lore of the Alien franchise. But to say that Prometheus isn’t an Alien film is a gross underestimation of the film’s audience. We really aren’t that stupid.

Of course people will argue that Ridley-dearest was telling the truth all along and that this film has nothing to do with Alien whatsoever. But put it this way – whether it involves our friendly local Xenomorph directly, we’re presented with the very origins of the Alien creature. It’s not the exact creature we know and love, but then thirty-or-so years can really change a man (or Xenomorph).

But it’s not all bad… right?

Despite its shortcomings, Prometheus does have a few things in its favor. The cinematography is beautiful and the CGI is flawless. The set design is something to behold and the inclusion of murals by H.R. Geiger will satisfy the diehard fans of the originals. To some extent. Unfortunately, that’s about as good as it gets. Prometheus lacks the tension of the originals and just isn’t anywhere near as frightening.

If you take Prometheus as a stand-alone film, then sure, it’s good enough. But that’s the biggest problem – it isn’t a stand-alone film. It will always be compared to the originals and in that respect, it simply falls flat. Ridley Scott stated early on that he didn’t want to simply remake Alien but instead, do something fresh. Except he hasn’t. Instead, he’s recycled the same old concepts and bundled them into a fresh, new package – an android with dubious motives, a survivalist female who fights to the bitter end, even a rugged yet charming space captain. Sound familiar? So in veering away from the original, what Ridley Scott has actually done is rehash the best bits in a way that makes them worse. Now, don’t get me wrong, Prometheus isn’t dreadful… it’s just not that good either.

So does Prometheus live up to the hype? Our new writer Imogen Reed investigates . . .

Ever since Prometheus was announced, fans have been driving themselves crazy with rumors and speculation. Everyone wanted to know more. Everyone wanted to see this. Years in the making, Ridley Scott’s dramatic return to the Alien franchise was bound to be an explosive one. Thankfully, the long wait is finally over and Prometheus has hit the cinema screens. But is it all it’s cracked up to be?

At first glance, it looks phenomenal. The trailer had fans worked into a frenzy before they set foot in the cinemas and the opening scenes were dramatic, mysterious and utterly tantalizing.

It’s a science-fiction film that seems to have it all – stunning special effects, brilliant actors and sets that just blow you away. The look and feel of Prometheus is entirely new and veers into the realms of ‘modern’ and ‘futuristic’ as opposed to the more grungy look of Alien. Even the ship’s interior is ultra-modern in its design – no hardwood coffee tables or sectional sofas here. But there is a distinct flavor of the Nostromo from the original films. The airlocks and corridors have that similar claustrophobic shape (albeit with a much more sleek appearance) and even the ships signage harks back to that old retro-futuristic font styling. It’s a similar feel throughout the film – something brand new with a familiar touch. Even down to the storyline.

So… is this a prequel or not?

I won’t go into the plot but whatever you’ve been told, do not believe the hype. There’s been numerous tall-tales going around that Prometheus isn’t an Alien film or that it’s only very remotely related. Some have even suggested that it’s simply ‘in the same universe’ as the originals. Even Ridley Scott himself has said in an interview that only “by the end of the third act you start to realize there’s a DNA of the very first Alien”. Unfortunately, somebody’s been telling porky-pies.

It’s true that there are differences – Prometheus is set a good thirty years before the events of Alien and it doesn’t tie in directly. For example, many believed that this film would explain the Space Jockey’s presence on LV-426, the planet where Ripley first encounters the Alien creature. That turned out not to be the case, but we are shown more of the Space Jockey’s race (referred to as The Engineers in Prometheus) and it essentially delves into the lore of the Alien franchise. But to say that Prometheus isn’t an Alien film is a gross underestimation of the film’s audience. We really aren’t that stupid.

Of course people will argue that Ridley-dearest was telling the truth all along and that this film has nothing to do with Alien whatsoever. But put it this way – whether it involves our friendly local Xenomorph directly, we’re presented with the very origins of the Alien creature. It’s not the exact creature we know and love, but then thirty-or-so years can really change a man (or Xenomorph).

But it’s not all bad… right?

Despite its shortcomings, Prometheus does have a few things in its favor. The cinematography is beautiful and the CGI is flawless. The set design is something to behold and the inclusion of murals by H.R. Geiger will satisfy the diehard fans of the originals. To some extent. Unfortunately, that’s about as good as it gets. Prometheus lacks the tension of the originals and just isn’t anywhere near as frightening.

If you take Prometheus as a stand-alone film, then sure, it’s good enough. But that’s the biggest problem – it isn’t a stand-alone film. It will always be compared to the originals and in that respect, it simply falls flat. Ridley Scott stated early on that he didn’t want to simply remake Alien but instead, do something fresh. Except he hasn’t. Instead, he’s recycled the same old concepts and bundled them into a fresh, new package – an android with dubious motives, a survivalist female who fights to the bitter end, even a rugged yet charming space captain. Sound familiar? So in veering away from the original, what Ridley Scott has actually done is rehash the best bits in a way that makes them worse. Now, don’t get me wrong, Prometheus isn’t dreadful… it’s just not that good either.

US Box Office last week

1. Madagascar 3: Europe’s Most Wanted – $35.5 million

2. Prometheus – $20.2 million

3. Rock of Ages – $15.1 million

4. Snow White and the Huntsman – $13.8 million

4. That’s My Boy – $13.0 million

Prometheus still doing well, but madagascar 3 burning hot, which i dun understand, such a crazy cartoon. Matrix, that is the inspiration of madagascar 3, really??

1. Madagascar 3: Europe’s Most Wanted – $35.5 million

2. Prometheus – $20.2 million

3. Rock of Ages – $15.1 million

4. Snow White and the Huntsman – $13.8 million

4. That’s My Boy – $13.0 million

Prometheus still doing well, but madagascar 3 burning hot, which i dun understand, such a crazy cartoon. Matrix, that is the inspiration of madagascar 3, really??

This 1 shown already?

yeah just a few days ago, nice try, a bit late. try again.

Yah, too lazy to click through all the pages. Pai seh, pai seh. After all the reviews, I think I might actually watch it now. Its like that transformers movie.

yeah just a few days ago, nice try, a bit late. try again.

is this a fan thread or a hate thread??

maybe this can explain some of the thinking behind some scenes. Got this from somewhere, not i write one.

To give some historical/mythological background that may shed some light, Ridley stated the SJ culture was based on Persian Myths. This would be Sumerian/Akkadian/Hindu. This is all taken from the Atra Hasis.

Creators - "G"ods- Annunaki - Dragon Humanoids (Naga, Dragon Kings,)

Helpers - "g"ods - Igigi - Engineers. (Android like living beings....BIOmechanical humanoid. Key features- Pale skin and large black eyes. Also known as watchers, Grigori, and Archons) (in many summerian texts they are actually referred to as "Pilots". Pretty much the Annunaki Air Force.)

When the Annunaki began terraforming the earth, they had the Igigi do the work for them. After a few thousand years the Igigi revolted and went on strike. The Annunaki then decided to create humans to do the work for them.

They sacrificed one of the rebel Igigi named Geshtu to use his blood and dna to make human beings, by mixing it with elements native to the earth.

(In the movie, this can be explained by the the different oval spaceship at the beginning representing the spaceship of the Annunaki)

(It can also be explained by the concept art that leaked from the official book this week)

(According to wikipedia it also says this about the Igigi: "Though sometimes synonymous with the term "Annunaki," in one myth the Igigi were the younger gods who were servants of the Annunaki, until they rebelled and were replaced by the creation of humans." This is reflectled exactly in the concept art below!)

Even though the humans were created and did the work, 1/3 of the Igigi still werent satisfied and sought revenge for Geshtu, so they rebelled again against the Annunaki Lords and began breeding/mixing with the human females creating Nephelim. This is what sparked the Prime Lord Enlil to flood the earth. Some humans were saved by Enki, the Lord responsible for the sacrifice of Geshtu and the creation of humans. Enlil and the rest of the annunaki decide to return home and let the humans develop on their own. Enki and his family stay behind. The Igigi are forced to leave earth as well. The remaining rebel Igigi are imprisoned on a planet on the way back to the homeworld and it is said as punishment and as a mark they are altered into a demonic appearance, no longer retaining the Angelic appearance.

Enki and his crew are probably the ones leaving the maps for humans to find, along with the ones helping humans advance throughout time.

The sacrfice engineer is Geshtu

The lone engineer is most likely Marduk or a servant/worshipper of Marduk.

The xeno is Mushussu, a creature Marduk fashioned and used as his pet.

The "Engineers" we see are trying to destroy Earth are of the Igigi rebels who view earth as their own. They have always despised humans because the Annunaki saw us as more in their likeness than them. IT's possible that the Igigi have long since destroyed or taken over the annunaki and the homeworld, and Earth was like going to claim the prize or spoils.

They mustve used to the Xeno's to win this war and through its perfection it has began to destroy and infect the Igigi who manufacture and transport it, creating more Mushussu.

the xeno in Alien is most likely an older pilot igigi birthed Mushussu egg crossed with human or a future Annunaki birthed one which would explain the size difference in hosts.

It is mentioned in several lesser stories that Marduk created the Mushussu out of using the essence of the Gods' (Annunaki) he killed as a symbol of his conquering and being able to control them... ie the mural.

maybe this can explain some of the thinking behind some scenes. Got this from somewhere, not i write one.

To give some historical/mythological background that may shed some light, Ridley stated the SJ culture was based on Persian Myths. This would be Sumerian/Akkadian/Hindu. This is all taken from the Atra Hasis.

Creators - "G"ods- Annunaki - Dragon Humanoids (Naga, Dragon Kings,)

Helpers - "g"ods - Igigi - Engineers. (Android like living beings....BIOmechanical humanoid. Key features- Pale skin and large black eyes. Also known as watchers, Grigori, and Archons) (in many summerian texts they are actually referred to as "Pilots". Pretty much the Annunaki Air Force.)

When the Annunaki began terraforming the earth, they had the Igigi do the work for them. After a few thousand years the Igigi revolted and went on strike. The Annunaki then decided to create humans to do the work for them.

They sacrificed one of the rebel Igigi named Geshtu to use his blood and dna to make human beings, by mixing it with elements native to the earth.

(In the movie, this can be explained by the the different oval spaceship at the beginning representing the spaceship of the Annunaki)

(It can also be explained by the concept art that leaked from the official book this week)

(According to wikipedia it also says this about the Igigi: "Though sometimes synonymous with the term "Annunaki," in one myth the Igigi were the younger gods who were servants of the Annunaki, until they rebelled and were replaced by the creation of humans." This is reflectled exactly in the concept art below!)

Even though the humans were created and did the work, 1/3 of the Igigi still werent satisfied and sought revenge for Geshtu, so they rebelled again against the Annunaki Lords and began breeding/mixing with the human females creating Nephelim. This is what sparked the Prime Lord Enlil to flood the earth. Some humans were saved by Enki, the Lord responsible for the sacrifice of Geshtu and the creation of humans. Enlil and the rest of the annunaki decide to return home and let the humans develop on their own. Enki and his family stay behind. The Igigi are forced to leave earth as well. The remaining rebel Igigi are imprisoned on a planet on the way back to the homeworld and it is said as punishment and as a mark they are altered into a demonic appearance, no longer retaining the Angelic appearance.

Enki and his crew are probably the ones leaving the maps for humans to find, along with the ones helping humans advance throughout time.

The sacrfice engineer is Geshtu

The lone engineer is most likely Marduk or a servant/worshipper of Marduk.

The xeno is Mushussu, a creature Marduk fashioned and used as his pet.

The "Engineers" we see are trying to destroy Earth are of the Igigi rebels who view earth as their own. They have always despised humans because the Annunaki saw us as more in their likeness than them. IT's possible that the Igigi have long since destroyed or taken over the annunaki and the homeworld, and Earth was like going to claim the prize or spoils.

They mustve used to the Xeno's to win this war and through its perfection it has began to destroy and infect the Igigi who manufacture and transport it, creating more Mushussu.

the xeno in Alien is most likely an older pilot igigi birthed Mushussu egg crossed with human or a future Annunaki birthed one which would explain the size difference in hosts.

It is mentioned in several lesser stories that Marduk created the Mushussu out of using the essence of the Gods' (Annunaki) he killed as a symbol of his conquering and being able to control them... ie the mural.

Last edited:

another one. this one better

Prometheus contains such a huge amount of mythic resonance that it effectively obscures a more conventional plot. I'd like to draw your attention to the use of motifs and callbacks in the film that not only enrich it, but offer possible hints as to what was going on in otherwise confusing scenes.

Let's begin with the eponymous titan himself, Prometheus. He was a wise and benevolent entity who created mankind in the first place, forming the first humans from clay. The Gods were more or less okay with that, until Prometheus gave them fire. This was a big no-no, as fire was supposed to be the exclusive property of the Gods. As punishment, Prometheus was chained to a rock and condemned to have his liver ripped out and eaten every day by an eagle. (His liver magically grew back, in case you were wondering.)

Fix that image in your mind, please: the giver of life, with his abdomen torn open. We'll be coming back to it many times in the course of this article.

The ethos of the titan Prometheus is one of willing and necessary sacrifice for life's sake. That's a pattern we see replicated throughout the ancient world. J G Frazer wrote his lengthy anthropological study, The Golden Bough, around the idea of the Dying God - a lifegiver who voluntarily dies for the sake of the people. It was incumbent upon the King to die at the right and proper time, because that was what heaven demanded, and fertility would not ensue if he did not do his royal duty of dying.

Now, consider the opening sequence of Prometheus. We fly over a spectacular vista, which may or may not be primordial Earth. According to Ridley Scott, it doesn't matter. A lone Engineer at the top of a waterfall goes through a strange ritual, drinking from a cup of black goo that causes his body to disintegrate into the building blocks of life. We see the fragments of his body falling into the river, twirling and spiralling into DNA helices.

Ridley Scott has this to say about the scene: 'That could be a planet anywhere. All he’s doing is acting as a gardener in space. And the plant life, in fact, is the disintegration of himself. If you parallel that idea with other sacrificial elements in history – which are clearly illustrated with the Mayans and the Incas – he would live for one year as a prince, and at the end of that year, he would be taken and donated to the gods in hopes of improving what might happen next year, be it with crops or weather, etcetera.'

Can we find a God in human history who creates plant life through his own death, and who is associated with a river? It's not difficult to find several, but the most obvious candidate is Osiris, the epitome of all the Frazerian 'Dying Gods'.

And we wouldn't be amiss in seeing the first of the movie's many Christian allegories in this scene, either. The Engineer removes his cloak before the ceremony, and hesitates before drinking the cupful of genetic solvent; he may well have been thinking 'If it be Thy will, let this cup pass from me.'

So, we know something about the Engineers, a founding principle laid down in the very first scene: acceptance of death, up to and including self-sacrifice, is right and proper in the creation of life. Prometheus, Osiris, John Barleycorn, and of course the Jesus of Christianity are all supposed to embody this same principle. It is held up as one of the most enduring human concepts of what it means to be 'good'.

Seen in this light, the perplexing obscurity of the rest of the film yields to an examination of the interwoven themes of sacrifice, creation, and preservation of life. We also discover, through hints, exactly what the nature of the clash between the Engineers and humanity entailed.

The crew of the Prometheus discover an ancient chamber, presided over by a brooding solemn face, in which urns of the same black substance are kept. A mural on the wall presents an image which, if you did as I asked earlier on, you will recognise instantly: the lifegiver with his abdomen torn open. Go and look at it here to refresh your memory. Note the serenity on the Engineer's face here.

And there's another mural there, one which shows a familiar xenomorph-like figure. This is the Destroyer who mirrors the Creator, I think - the avatar of supremely selfish life, devouring and destroying others purely to preserve itself. As Ash puts it: 'a survivor, unclouded by conscience, remorse or delusions of morality.'

Through Shaw and Holloway's investigations, we learn that the Engineers not only created human life, they supervised our development. (How else are we to explain the numerous images of Engineers in primitive art, complete with star diagram showing us the way to find them?) We have to assume, then, that for a good few hundred thousand years, they were pretty happy with us. They could have destroyed us at any time, but instead, they effectively invited us over; the big pointy finger seems to be saying 'Hey, guys, when you're grown up enough to develop space travel, come see us.' Until something changed, something which not only messed up our relationship with them but caused their installation on LV-223 to be almost entirely wiped out.

From the Engineers' perspective, so long as humans retained that notion of self-sacrifice as central, we weren't entirely beyond redemption. But we went and screwed it all up, and the film hints at when, if not why: the Engineers at the base died two thousand years ago. That suggests that the event that turned them against us and led to the huge piles of dead Engineers lying about was one and the same event. We did something very, very bad, and somehow the consequences of that dreadful act accompanied the Engineers back to LV-223 and massacred them.

If you have uneasy suspicions about what 'a bad thing approximately 2,000 years ago' might be, then let me reassure you that you are right. An astonishing excerpt from the Movies.com interview with Ridley Scott:

Movies.com: We had heard it was scripted that the Engineers were targeting our planet for destruction because we had crucified one of their representatives, and that Jesus Christ might have been an alien. Was that ever considered?

Ridley Scott: We definitely did, and then we thought it was a little too on the nose. But if you look at it as an “our children are misbehaving down there” scenario, there are moments where it looks like we’ve gone out of control, running around with armor and skirts, which of course would be the Roman Empire. And they were given a long run. A thousand years before their disintegration actually started to happen. And you can say, "Let's send down one more of our emissaries to see if he can stop it." Guess what? They crucified him.

Yeah. The reason the Engineers don't like us any more is that they made us a Space Jesus, and we broke him. Reader, that's not me pulling wild ideas out of my arse. That's RIDLEY SCOTT.

So, imagine poor crucified Jesus, a fresh spear wound in his side. Oh, hey, there's the 'lifegiver with his abdomen torn open' motif again. That's three times now: Prometheus, Engineer mural, Jesus Christ. And I don't think I have to mention the 'sacrifice in the interest of giving life' bit again, do I? Everyone on the same page? Good.

So how did our (in the context of the film) terrible murderous act of crucifixion end up wiping out all but one of the Engineers back on LV-223? Presumably through the black slime, which evidently models its behaviour on the user's mental state. Create unselfishly, accepting self-destruction as the cost, and the black stuff engenders fertile life. But expose the potent black slimy stuff to the thoughts and emotions of flawed humanity, and 'the sleep of reason produces monsters'. We never see the threat that the Engineers were fleeing from, we never see them killed other than accidentally (decapitation by door), and we see no remaining trace of whatever killed them. Either it left a long time ago, or it reverted to inert black slime, waiting for a human mind to reactivate it.

The black slime reacts to the nature and intent of the being that wields it, and the humans in the film didn't even know that they WERE wielding it. That's why it remained completely inert in David's presence, and why he needed a human proxy in order to use the stuff to create anything. The black goo could read no emotion or intent from him, because he was an android.

Shaw's comment when the urn chamber is entered - 'we've changed the atmosphere in the room' - is deceptively informative. The psychic atmosphere has changed, because humans - tainted, Space Jesus-killing humans - are present. The slime begins to engender new life, drawing not from a self-sacrificing Engineer but from human hunger for knowledge, for more life, for more everything. Little wonder, then, that it takes serpent-like form. The symbolism of a corrupting serpent, turning men into beasts, is pretty unmistakeable.

Refusal to accept death is anathema to the Engineers. Right from the first scene, we learned their code of willing self-sacrifice in accord with a greater purpose. When the severed Engineer head is temporarily brought back to life, its expression registers horror and disgust. Cinemagoers are confused when the head explodes, because it's not clear why it should have done so. Perhaps the Engineer wanted to die again, to undo the tainted human agenda of new life without sacrifice.

But some humans do act in ways the Engineers might have grudgingly admired. Take Holloway, Shaw's lover, who impregnates her barren womb with his black slime riddled semen before realising he is being transformed into something Other. Unlike the hapless geologist and botanist left behind in the chamber, who only want to stay alive, Holloway willingly embraces death. He all but invites Meredith Vickers to kill him, and it's surely significant that she does so using fire, the other gift Prometheus gave to man besides his life.

The 'Caesarean' scene is central to the film's themes of creation, sacrifice, and giving life. Shaw has discovered she's pregnant with something non-human and sets the autodoc to slice it out of her. She lies there screaming, a gaping wound in her stomach, while her tentacled alien child thrashes and squeals in the clamp above her and OH HEY IT'S THE LIFEGIVER WITH HER ABDOMEN TORN OPEN. How many times has that image come up now? Four, I make it. (We're not done yet.)

And she doesn't kill it. And she calls the procedure a 'caesarean' instead of an 'abortion'.

(I'm not even going to begin to explore the pro-choice versus forced birth implications of that scene. I don't think they're clear, and I'm not entirely comfortable doing so. Let's just say that her unwanted offspring turning out to be her salvation is possibly problematic from a feminist standpoint and leave it there for now.)

Here's where the Christian allegories really come through. The day of this strange birth just happens to be Christmas Day. And this is a 'virgin birth' of sorts, although a dark and twisted one, because Shaw couldn't possibly be pregnant. And Shaw's the crucifix-wearing Christian of the crew. We may well ask, echoing Yeats: what rough beast, its hour come round at last, slouches towards LV-223 to be born?

Consider the scene where David tells Shaw that she's pregnant, and tell me that's not a riff on the Annunciation. The calm, graciously angelic android delivering the news, the pious mother who insists she can't possibly be pregnant, the wry declaration that it's no ordinary child... yeah, we've seen this before.

'And the angel answered and said unto her, The Holy Ghost shall come upon thee, and the power of the Highest shall overshadow thee: therefore also that holy thing which shall be born of thee shall be called the Son of God. And, behold, thy cousin Elisabeth, she hath also conceived a son in her old age: and this is the sixth month with her, who was called barren.'

A barren woman called Elizabeth, made pregnant by 'God'? Subtle, Ridley.

Anyway. If it weren't already clear enough that the central theme of the film is 'I suffer and die so that others may live' versus 'you suffer and die so that I may live' writ extremely large, Meredith Vickers helpfully spells it out:

'A king has his reign, and then he dies. It's inevitable.'

Vickers is not just speaking out of personal frustration here, though that's obviously one level of it. She wants her father out of the way, so she can finally come in to her inheritance. It's insult enough that Weyland describes the android David as 'the closest thing I have to a son', as if only a male heir was of any worth; his obstinate refusal to accept death is a slap in her face.

Weyland, preserved by his wealth and the technology it can buy, has lived far, far longer than his rightful time. A ghoulish, wizened creature who looks neither old nor young, he reminds me of Slough Feg, the decaying tyrant from the Slaine series in British comic 2000AD. In Slaine, an ancient (and by now familiar to you, dear reader, or so I would hope) Celtic law decrees that the King has to be ritually and willingly sacrificed at the end of his appointed time, for the good of the land and the people. Slough Feg refused to die, and became a rotting horror, the embodiment of evil.

The image of the sorcerer who refuses to accept rightful death is fundamental: it even forms a part of some occult philosophy. In Crowley's system, the magician who refuses to accept the bitter cup of Babalon and undergo dissolution of his individual ego in the Great Sea (remember that opening scene?) becomes an ossified, corrupted entity called a 'Black Brother' who can create no new life, and lives on as a sterile, emasculated husk.

With all this in mind, we can better understand the climactic scene in which the withered Weyland confronts the last surviving Engineer. See it from the Engineer's perspective. Two thousand years ago, humanity not only murdered the Engineers' emissary, it infected the Engineers' life-creating fluid with its own tainted selfish nature, creating monsters. And now, after so long, here humanity is, presumptuously accepting a long-overdue invitation, and even reawakening (and corrupting all over again) the life fluid.

And who has humanity chosen to represent them? A self-centred, self-satisfied narcissist who revels in his own artificially extended life, who speaks through the medium of a merely mechanical offspring. Humanity couldn't have chosen a worse ambassador.

It's hardly surprising that the Engineer reacts with contempt and disgust, ripping David's head off and battering Weyland to death with it. The subtext is bitter and ironic: you caused us to die at the hands of our own creation, so I am going to kill you with YOUR own creation, albeit in a crude and bludgeoning way.

The only way to save humanity is through self-sacrifice, and this is exactly what the captain (and his two oddly complacent co-pilots) opt to do. They crash the Prometheus into the Engineer's ship, giving up their lives in order to save others. Their willing self-sacrifice stands alongside Holloway's and the Engineer's from the opening sequence; by now, the film has racked up no less than five self-sacrificing gestures (six if we consider the exploding Engineer head).

Meredith Vickers, of course, has no interest in self-sacrifice. Like her father, she wants to keep herself alive, and so she ejects and lands on the planet's surface. With the surviving cast now down to Vickers and Shaw, we witness Vickers's rather silly death as the Engineer ship rolls over and crushes her, due to a sudden inability on her part to run sideways. Perhaps that's the point; perhaps the film is saying her view is blinkered, and ultimately that kills her. But I doubt it. Sometimes a daft death is just a daft death.

Finally, in the squidgy ending scenes of the film, the wrathful Engineer conveniently meets its death at the tentacles of Shaw's alien child, now somehow grown huge. But it's not just a death; there's obscene life being created here, too. The (in the Engineers' eyes) horrific human impulse to sacrifice others in order to survive has taken on flesh. The Engineer's body bursts open - blah blah lifegiver blah blah abdomen ripped apart hey we're up to five now - and the proto-Alien that emerges is the very image of the creature from the mural.

On the face of it, it seems absurd to suggest that the genesis of the Alien xenomorph ultimately lies in the grotesque human act of crucifying the Space Jockeys' emissary to Israel in four B.C., but that's what Ridley Scott proposes. It seems equally insane to propose that Prometheus is fundamentally about the clash between acceptance of death as a condition of creating/sustaining life versus clinging on to life at the expense of others, but the repeated, insistent use of motifs and themes bears this out.

As a closing point, let me draw your attention to a very different strand of symbolism that runs through Prometheus: the British science fiction show Doctor Who. In the 1970s episode 'The Daemons', an ancient mound is opened up, leading to an encounter with a gigantic being who proves to be an alien responsible for having guided mankind's development, and who now views mankind as a failed experiment that must be destroyed. The Engineers are seen tootling on flutes, in exactly the same way that the second Doctor does. The Third Doctor had an companion whose name was Liz Shaw, the same name as the protagonist of Prometheus. As with anything else in the film, it could all be coincidental; but knowing Ridley Scott, it doesn't seem very likely.

Prometheus contains such a huge amount of mythic resonance that it effectively obscures a more conventional plot. I'd like to draw your attention to the use of motifs and callbacks in the film that not only enrich it, but offer possible hints as to what was going on in otherwise confusing scenes.

Let's begin with the eponymous titan himself, Prometheus. He was a wise and benevolent entity who created mankind in the first place, forming the first humans from clay. The Gods were more or less okay with that, until Prometheus gave them fire. This was a big no-no, as fire was supposed to be the exclusive property of the Gods. As punishment, Prometheus was chained to a rock and condemned to have his liver ripped out and eaten every day by an eagle. (His liver magically grew back, in case you were wondering.)

Fix that image in your mind, please: the giver of life, with his abdomen torn open. We'll be coming back to it many times in the course of this article.

The ethos of the titan Prometheus is one of willing and necessary sacrifice for life's sake. That's a pattern we see replicated throughout the ancient world. J G Frazer wrote his lengthy anthropological study, The Golden Bough, around the idea of the Dying God - a lifegiver who voluntarily dies for the sake of the people. It was incumbent upon the King to die at the right and proper time, because that was what heaven demanded, and fertility would not ensue if he did not do his royal duty of dying.

Now, consider the opening sequence of Prometheus. We fly over a spectacular vista, which may or may not be primordial Earth. According to Ridley Scott, it doesn't matter. A lone Engineer at the top of a waterfall goes through a strange ritual, drinking from a cup of black goo that causes his body to disintegrate into the building blocks of life. We see the fragments of his body falling into the river, twirling and spiralling into DNA helices.

Ridley Scott has this to say about the scene: 'That could be a planet anywhere. All he’s doing is acting as a gardener in space. And the plant life, in fact, is the disintegration of himself. If you parallel that idea with other sacrificial elements in history – which are clearly illustrated with the Mayans and the Incas – he would live for one year as a prince, and at the end of that year, he would be taken and donated to the gods in hopes of improving what might happen next year, be it with crops or weather, etcetera.'

Can we find a God in human history who creates plant life through his own death, and who is associated with a river? It's not difficult to find several, but the most obvious candidate is Osiris, the epitome of all the Frazerian 'Dying Gods'.

And we wouldn't be amiss in seeing the first of the movie's many Christian allegories in this scene, either. The Engineer removes his cloak before the ceremony, and hesitates before drinking the cupful of genetic solvent; he may well have been thinking 'If it be Thy will, let this cup pass from me.'

So, we know something about the Engineers, a founding principle laid down in the very first scene: acceptance of death, up to and including self-sacrifice, is right and proper in the creation of life. Prometheus, Osiris, John Barleycorn, and of course the Jesus of Christianity are all supposed to embody this same principle. It is held up as one of the most enduring human concepts of what it means to be 'good'.

Seen in this light, the perplexing obscurity of the rest of the film yields to an examination of the interwoven themes of sacrifice, creation, and preservation of life. We also discover, through hints, exactly what the nature of the clash between the Engineers and humanity entailed.

The crew of the Prometheus discover an ancient chamber, presided over by a brooding solemn face, in which urns of the same black substance are kept. A mural on the wall presents an image which, if you did as I asked earlier on, you will recognise instantly: the lifegiver with his abdomen torn open. Go and look at it here to refresh your memory. Note the serenity on the Engineer's face here.

And there's another mural there, one which shows a familiar xenomorph-like figure. This is the Destroyer who mirrors the Creator, I think - the avatar of supremely selfish life, devouring and destroying others purely to preserve itself. As Ash puts it: 'a survivor, unclouded by conscience, remorse or delusions of morality.'

Through Shaw and Holloway's investigations, we learn that the Engineers not only created human life, they supervised our development. (How else are we to explain the numerous images of Engineers in primitive art, complete with star diagram showing us the way to find them?) We have to assume, then, that for a good few hundred thousand years, they were pretty happy with us. They could have destroyed us at any time, but instead, they effectively invited us over; the big pointy finger seems to be saying 'Hey, guys, when you're grown up enough to develop space travel, come see us.' Until something changed, something which not only messed up our relationship with them but caused their installation on LV-223 to be almost entirely wiped out.

From the Engineers' perspective, so long as humans retained that notion of self-sacrifice as central, we weren't entirely beyond redemption. But we went and screwed it all up, and the film hints at when, if not why: the Engineers at the base died two thousand years ago. That suggests that the event that turned them against us and led to the huge piles of dead Engineers lying about was one and the same event. We did something very, very bad, and somehow the consequences of that dreadful act accompanied the Engineers back to LV-223 and massacred them.

If you have uneasy suspicions about what 'a bad thing approximately 2,000 years ago' might be, then let me reassure you that you are right. An astonishing excerpt from the Movies.com interview with Ridley Scott:

Movies.com: We had heard it was scripted that the Engineers were targeting our planet for destruction because we had crucified one of their representatives, and that Jesus Christ might have been an alien. Was that ever considered?

Ridley Scott: We definitely did, and then we thought it was a little too on the nose. But if you look at it as an “our children are misbehaving down there” scenario, there are moments where it looks like we’ve gone out of control, running around with armor and skirts, which of course would be the Roman Empire. And they were given a long run. A thousand years before their disintegration actually started to happen. And you can say, "Let's send down one more of our emissaries to see if he can stop it." Guess what? They crucified him.

Yeah. The reason the Engineers don't like us any more is that they made us a Space Jesus, and we broke him. Reader, that's not me pulling wild ideas out of my arse. That's RIDLEY SCOTT.

So, imagine poor crucified Jesus, a fresh spear wound in his side. Oh, hey, there's the 'lifegiver with his abdomen torn open' motif again. That's three times now: Prometheus, Engineer mural, Jesus Christ. And I don't think I have to mention the 'sacrifice in the interest of giving life' bit again, do I? Everyone on the same page? Good.

So how did our (in the context of the film) terrible murderous act of crucifixion end up wiping out all but one of the Engineers back on LV-223? Presumably through the black slime, which evidently models its behaviour on the user's mental state. Create unselfishly, accepting self-destruction as the cost, and the black stuff engenders fertile life. But expose the potent black slimy stuff to the thoughts and emotions of flawed humanity, and 'the sleep of reason produces monsters'. We never see the threat that the Engineers were fleeing from, we never see them killed other than accidentally (decapitation by door), and we see no remaining trace of whatever killed them. Either it left a long time ago, or it reverted to inert black slime, waiting for a human mind to reactivate it.

The black slime reacts to the nature and intent of the being that wields it, and the humans in the film didn't even know that they WERE wielding it. That's why it remained completely inert in David's presence, and why he needed a human proxy in order to use the stuff to create anything. The black goo could read no emotion or intent from him, because he was an android.

Shaw's comment when the urn chamber is entered - 'we've changed the atmosphere in the room' - is deceptively informative. The psychic atmosphere has changed, because humans - tainted, Space Jesus-killing humans - are present. The slime begins to engender new life, drawing not from a self-sacrificing Engineer but from human hunger for knowledge, for more life, for more everything. Little wonder, then, that it takes serpent-like form. The symbolism of a corrupting serpent, turning men into beasts, is pretty unmistakeable.

Refusal to accept death is anathema to the Engineers. Right from the first scene, we learned their code of willing self-sacrifice in accord with a greater purpose. When the severed Engineer head is temporarily brought back to life, its expression registers horror and disgust. Cinemagoers are confused when the head explodes, because it's not clear why it should have done so. Perhaps the Engineer wanted to die again, to undo the tainted human agenda of new life without sacrifice.

But some humans do act in ways the Engineers might have grudgingly admired. Take Holloway, Shaw's lover, who impregnates her barren womb with his black slime riddled semen before realising he is being transformed into something Other. Unlike the hapless geologist and botanist left behind in the chamber, who only want to stay alive, Holloway willingly embraces death. He all but invites Meredith Vickers to kill him, and it's surely significant that she does so using fire, the other gift Prometheus gave to man besides his life.

The 'Caesarean' scene is central to the film's themes of creation, sacrifice, and giving life. Shaw has discovered she's pregnant with something non-human and sets the autodoc to slice it out of her. She lies there screaming, a gaping wound in her stomach, while her tentacled alien child thrashes and squeals in the clamp above her and OH HEY IT'S THE LIFEGIVER WITH HER ABDOMEN TORN OPEN. How many times has that image come up now? Four, I make it. (We're not done yet.)

And she doesn't kill it. And she calls the procedure a 'caesarean' instead of an 'abortion'.

(I'm not even going to begin to explore the pro-choice versus forced birth implications of that scene. I don't think they're clear, and I'm not entirely comfortable doing so. Let's just say that her unwanted offspring turning out to be her salvation is possibly problematic from a feminist standpoint and leave it there for now.)

Here's where the Christian allegories really come through. The day of this strange birth just happens to be Christmas Day. And this is a 'virgin birth' of sorts, although a dark and twisted one, because Shaw couldn't possibly be pregnant. And Shaw's the crucifix-wearing Christian of the crew. We may well ask, echoing Yeats: what rough beast, its hour come round at last, slouches towards LV-223 to be born?

Consider the scene where David tells Shaw that she's pregnant, and tell me that's not a riff on the Annunciation. The calm, graciously angelic android delivering the news, the pious mother who insists she can't possibly be pregnant, the wry declaration that it's no ordinary child... yeah, we've seen this before.

'And the angel answered and said unto her, The Holy Ghost shall come upon thee, and the power of the Highest shall overshadow thee: therefore also that holy thing which shall be born of thee shall be called the Son of God. And, behold, thy cousin Elisabeth, she hath also conceived a son in her old age: and this is the sixth month with her, who was called barren.'

A barren woman called Elizabeth, made pregnant by 'God'? Subtle, Ridley.

Anyway. If it weren't already clear enough that the central theme of the film is 'I suffer and die so that others may live' versus 'you suffer and die so that I may live' writ extremely large, Meredith Vickers helpfully spells it out:

'A king has his reign, and then he dies. It's inevitable.'

Vickers is not just speaking out of personal frustration here, though that's obviously one level of it. She wants her father out of the way, so she can finally come in to her inheritance. It's insult enough that Weyland describes the android David as 'the closest thing I have to a son', as if only a male heir was of any worth; his obstinate refusal to accept death is a slap in her face.

Weyland, preserved by his wealth and the technology it can buy, has lived far, far longer than his rightful time. A ghoulish, wizened creature who looks neither old nor young, he reminds me of Slough Feg, the decaying tyrant from the Slaine series in British comic 2000AD. In Slaine, an ancient (and by now familiar to you, dear reader, or so I would hope) Celtic law decrees that the King has to be ritually and willingly sacrificed at the end of his appointed time, for the good of the land and the people. Slough Feg refused to die, and became a rotting horror, the embodiment of evil.

The image of the sorcerer who refuses to accept rightful death is fundamental: it even forms a part of some occult philosophy. In Crowley's system, the magician who refuses to accept the bitter cup of Babalon and undergo dissolution of his individual ego in the Great Sea (remember that opening scene?) becomes an ossified, corrupted entity called a 'Black Brother' who can create no new life, and lives on as a sterile, emasculated husk.

With all this in mind, we can better understand the climactic scene in which the withered Weyland confronts the last surviving Engineer. See it from the Engineer's perspective. Two thousand years ago, humanity not only murdered the Engineers' emissary, it infected the Engineers' life-creating fluid with its own tainted selfish nature, creating monsters. And now, after so long, here humanity is, presumptuously accepting a long-overdue invitation, and even reawakening (and corrupting all over again) the life fluid.

And who has humanity chosen to represent them? A self-centred, self-satisfied narcissist who revels in his own artificially extended life, who speaks through the medium of a merely mechanical offspring. Humanity couldn't have chosen a worse ambassador.

It's hardly surprising that the Engineer reacts with contempt and disgust, ripping David's head off and battering Weyland to death with it. The subtext is bitter and ironic: you caused us to die at the hands of our own creation, so I am going to kill you with YOUR own creation, albeit in a crude and bludgeoning way.

The only way to save humanity is through self-sacrifice, and this is exactly what the captain (and his two oddly complacent co-pilots) opt to do. They crash the Prometheus into the Engineer's ship, giving up their lives in order to save others. Their willing self-sacrifice stands alongside Holloway's and the Engineer's from the opening sequence; by now, the film has racked up no less than five self-sacrificing gestures (six if we consider the exploding Engineer head).

Meredith Vickers, of course, has no interest in self-sacrifice. Like her father, she wants to keep herself alive, and so she ejects and lands on the planet's surface. With the surviving cast now down to Vickers and Shaw, we witness Vickers's rather silly death as the Engineer ship rolls over and crushes her, due to a sudden inability on her part to run sideways. Perhaps that's the point; perhaps the film is saying her view is blinkered, and ultimately that kills her. But I doubt it. Sometimes a daft death is just a daft death.

Finally, in the squidgy ending scenes of the film, the wrathful Engineer conveniently meets its death at the tentacles of Shaw's alien child, now somehow grown huge. But it's not just a death; there's obscene life being created here, too. The (in the Engineers' eyes) horrific human impulse to sacrifice others in order to survive has taken on flesh. The Engineer's body bursts open - blah blah lifegiver blah blah abdomen ripped apart hey we're up to five now - and the proto-Alien that emerges is the very image of the creature from the mural.

On the face of it, it seems absurd to suggest that the genesis of the Alien xenomorph ultimately lies in the grotesque human act of crucifying the Space Jockeys' emissary to Israel in four B.C., but that's what Ridley Scott proposes. It seems equally insane to propose that Prometheus is fundamentally about the clash between acceptance of death as a condition of creating/sustaining life versus clinging on to life at the expense of others, but the repeated, insistent use of motifs and themes bears this out.

As a closing point, let me draw your attention to a very different strand of symbolism that runs through Prometheus: the British science fiction show Doctor Who. In the 1970s episode 'The Daemons', an ancient mound is opened up, leading to an encounter with a gigantic being who proves to be an alien responsible for having guided mankind's development, and who now views mankind as a failed experiment that must be destroyed. The Engineers are seen tootling on flutes, in exactly the same way that the second Doctor does. The Third Doctor had an companion whose name was Liz Shaw, the same name as the protagonist of Prometheus. As with anything else in the film, it could all be coincidental; but knowing Ridley Scott, it doesn't seem very likely.

Last edited:

Yah, too lazy to click through all the pages. Pai seh, pai seh. After all the reviews, I think I might actually watch it now. Its like that transformers movie.

go and watch the movie. To better understand what we are talking about here. It is a movie with plot hole like swiss cheese, ask many questions but have no answer.

another one. this one better

oMG , so long, you expect moi to read it all?

jesus, summaries man.

After reading that review, I'm really intrigue to watch it now. Seems to be more consistent then transformer.

oMG , so long, you expect moi to read it all?

jesus, summaries man.

What did Michael Fassbender say at the end of 'Prometheus'? Language consultant reveals all

Ridley Scott’s Prometheus prompted a lot of questions from cinemagoers, like “What the f—?” and “No, seriously: What the f—?” We can’t provide answers for either of those queries. But we can resolve the question of what Michael Fassbender’s android David said to the Engineer just prior to the alien going ape and trying to kill everyone in sight.

Movie website The Bioscopist tracked down linguistic expert Dr. Anil Biltoo of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies. In Prometheus, a projection of Biltoo acts as David’s language tutor, and in real-life Biltoo worked as a consultant on the film. According to the doctor, the line of alien dialog David speaks in the film “serviceably” translates as “This man is here because he does not want to die. He believes you can give him more life.” The “Man” in question is, of course, Guy Pearce’s expedition-financing Peter Weyland and, as that is pretty much a recitation of the businessman’s already established plan, it doesn’t come as a big surprise nor resolve the issue of our big white buddy’s subsequent freak-out.

But Dr. Biltoo also says that originally David and the Engineer had “a conversation, not merely an utterance from David” and that “We’re all going to have to wait for the director’s cut to see if the conversation…yields any fruit.”

Ridley Scott’s Prometheus prompted a lot of questions from cinemagoers, like “What the f—?” and “No, seriously: What the f—?” We can’t provide answers for either of those queries. But we can resolve the question of what Michael Fassbender’s android David said to the Engineer just prior to the alien going ape and trying to kill everyone in sight.

Movie website The Bioscopist tracked down linguistic expert Dr. Anil Biltoo of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies. In Prometheus, a projection of Biltoo acts as David’s language tutor, and in real-life Biltoo worked as a consultant on the film. According to the doctor, the line of alien dialog David speaks in the film “serviceably” translates as “This man is here because he does not want to die. He believes you can give him more life.” The “Man” in question is, of course, Guy Pearce’s expedition-financing Peter Weyland and, as that is pretty much a recitation of the businessman’s already established plan, it doesn’t come as a big surprise nor resolve the issue of our big white buddy’s subsequent freak-out.

But Dr. Biltoo also says that originally David and the Engineer had “a conversation, not merely an utterance from David” and that “We’re all going to have to wait for the director’s cut to see if the conversation…yields any fruit.”

Scott Hansen column: Flaws end up burning "Prometheus"

So yes, we are in the midst of what is known as the dog days of summer movies.

Typically between the Memorial Day weekend and July 4, the movie-going public sits at a table occupied by films such as "Battleship," "Transformers 2," "Transformers 3," "Speed 2," "Batman and Robin" and "Godzilla," so it's no wonder that when a thoughtful guest such as "Prometheus" arrives, things get a bit more interesting.

It's hard to fault the recently released Ridley Scott film "Prometheus" for raising lots of questions. Whether it pertains to how humans came to be, why were created in the first place, or how faith and science should intertwine, the "Alien" un-prequel that was co-written by "Lost" scribe Damon Lindelof certainly has no issue with leaving its audience puzzled.

But while many are heralding it as a great film because it's one of the few summer movies that has something to say, I can't help but think it's not a good movie and it moreso says something about what we as movie-goers have come to subconsciously think -- just because a movie raises questions and is thought-provoking when released in June, that automatically makes it good.

But "Prometheus," as thought-provoking as it is, is a deeply flawed film. Applaud the ambition, mourn the missed opportunity, as they say.

For starters, the film presents its audience with an incredibly unlikable cast of characters with each being overt representations of various positions taken by those present in the debate of science vs. religion -- Noomi Rapace's Elizabeth Shaw (an archaeologist with a very strong faith), Logan Marshall-Green's Charlie Holloway (someone who seems to take on the beliefs of his significant other), Charlize Theron's Meredith Vickers (a character sent to monitor the expedition who wants to control the situation but observes from the outside) and Michael Fassbender's David (an android who seems to be self aware that his knowledge is superior to others).

Shaw is whiny and subtly cocky, Holloway treats people not named Elizabeth as second-class citizens, Vickers is cranky for no reason and David doesn't seem to value anyone except for himself.

From there, the audience is supplied a narrative full of illogical decision making by the band of misfits that doesn't make sense based upon the traits they display in the film's excellent first act.

While Holloway can best be described as a think-before-he-acts jerk, early on, he comes across as a loving boyfriend interested in the evolution of human beings. Then, without really any motives, he begins to act recklessly and proceeds to treat others poorly until karma has its way with him in an attempt to make the audience fine with his demise. Surprisingly, this doesn't occur when, despite being portrayed as logical, he takes off his helmet on the alien planet just because he detects oxygen.

Later, a biologist who shows early signs of vulnerability and skittishness around a 10,000-year-old corpse becomes brave enough to confront a phallic creature only to meet his demise. Of course, that comes after his map-tech partner somehow gets the pair lost in what was portrayed as a one-way tunnel.

For the most part, though, we can count on Vickers being the smart one of the group. But somehow, in the film's finale, she runs in a straight line in an attempt to outrun an object rolling right at her.

As illogical as the characters act, though, they at least are in a universe where illogical things seem to occur on the regular -- all life forms on Earth share DNA with our creators but somehow not everything on Earth shares our same DNA.

"Prometheus" has a laundry list full of two things -- questions and flaws. While the first is an asset, the latter is a weakness only heightened by how much of it is shown. Sure, a June movie asking questions is admirable, and we can only hope that more films similar in style to "Prometheus" emerge in the coming years. But let's not forget that just because it is released in a certain month doesn't mean it gets a free pass for things it sorely lacks and for things it doesn't do very well.

So yes, we are in the midst of what is known as the dog days of summer movies.

Typically between the Memorial Day weekend and July 4, the movie-going public sits at a table occupied by films such as "Battleship," "Transformers 2," "Transformers 3," "Speed 2," "Batman and Robin" and "Godzilla," so it's no wonder that when a thoughtful guest such as "Prometheus" arrives, things get a bit more interesting.

It's hard to fault the recently released Ridley Scott film "Prometheus" for raising lots of questions. Whether it pertains to how humans came to be, why were created in the first place, or how faith and science should intertwine, the "Alien" un-prequel that was co-written by "Lost" scribe Damon Lindelof certainly has no issue with leaving its audience puzzled.

But while many are heralding it as a great film because it's one of the few summer movies that has something to say, I can't help but think it's not a good movie and it moreso says something about what we as movie-goers have come to subconsciously think -- just because a movie raises questions and is thought-provoking when released in June, that automatically makes it good.

But "Prometheus," as thought-provoking as it is, is a deeply flawed film. Applaud the ambition, mourn the missed opportunity, as they say.

For starters, the film presents its audience with an incredibly unlikable cast of characters with each being overt representations of various positions taken by those present in the debate of science vs. religion -- Noomi Rapace's Elizabeth Shaw (an archaeologist with a very strong faith), Logan Marshall-Green's Charlie Holloway (someone who seems to take on the beliefs of his significant other), Charlize Theron's Meredith Vickers (a character sent to monitor the expedition who wants to control the situation but observes from the outside) and Michael Fassbender's David (an android who seems to be self aware that his knowledge is superior to others).

Shaw is whiny and subtly cocky, Holloway treats people not named Elizabeth as second-class citizens, Vickers is cranky for no reason and David doesn't seem to value anyone except for himself.

From there, the audience is supplied a narrative full of illogical decision making by the band of misfits that doesn't make sense based upon the traits they display in the film's excellent first act.

While Holloway can best be described as a think-before-he-acts jerk, early on, he comes across as a loving boyfriend interested in the evolution of human beings. Then, without really any motives, he begins to act recklessly and proceeds to treat others poorly until karma has its way with him in an attempt to make the audience fine with his demise. Surprisingly, this doesn't occur when, despite being portrayed as logical, he takes off his helmet on the alien planet just because he detects oxygen.

Later, a biologist who shows early signs of vulnerability and skittishness around a 10,000-year-old corpse becomes brave enough to confront a phallic creature only to meet his demise. Of course, that comes after his map-tech partner somehow gets the pair lost in what was portrayed as a one-way tunnel.

For the most part, though, we can count on Vickers being the smart one of the group. But somehow, in the film's finale, she runs in a straight line in an attempt to outrun an object rolling right at her.

As illogical as the characters act, though, they at least are in a universe where illogical things seem to occur on the regular -- all life forms on Earth share DNA with our creators but somehow not everything on Earth shares our same DNA.

"Prometheus" has a laundry list full of two things -- questions and flaws. While the first is an asset, the latter is a weakness only heightened by how much of it is shown. Sure, a June movie asking questions is admirable, and we can only hope that more films similar in style to "Prometheus" emerge in the coming years. But let's not forget that just because it is released in a certain month doesn't mean it gets a free pass for things it sorely lacks and for things it doesn't do very well.

Prometheus still flying high at U.K. box office

Alien prequel Prometheus has held onto its place at the top of the U.K. box office chart for the third consecutive weekend (15-17Jun12).

The sci-fi blockbuster, starring Michael Fassbender, took $3.1 million (£2 million) in ticket sales, beating Men in Black III which came in second, banking $2.4 million (£1.5 million), and Snow White and The Huntsman, which charted third and took $2 million (163;1.3 million).

The big screen adaptation of stage production Rock of Ages debuted in fourth place, taking $1.6 million (£1 million).

Completing the top five, the previous weekend's (8-10Jun12) number four, The Pact, dropped one place, taking $750,000 (£476,000).

Alien prequel Prometheus has held onto its place at the top of the U.K. box office chart for the third consecutive weekend (15-17Jun12).

The sci-fi blockbuster, starring Michael Fassbender, took $3.1 million (£2 million) in ticket sales, beating Men in Black III which came in second, banking $2.4 million (£1.5 million), and Snow White and The Huntsman, which charted third and took $2 million (163;1.3 million).

The big screen adaptation of stage production Rock of Ages debuted in fourth place, taking $1.6 million (£1 million).

Completing the top five, the previous weekend's (8-10Jun12) number four, The Pact, dropped one place, taking $750,000 (£476,000).

Prometheus – review

Ridley Scott's return to the Alien universe is grandiose and muddled – with a scene-stealing Michael Fassbender performance

A kind of idealism … Prometheus.

Ridley Scott has counter-evolved his 1979 classic Alien into something more grandiose, more elaborate – but less interesting. In place of scariness there is wonderment; in place of tension there is hugely ambitious design; in place of unforgettable shocks there are reminders of the original's unforgettable shocks. There are also some shrewd and witty touches, and one terrifically creepy performance from Michael Fassbender, who steals the film with the chilling, parasitic relentlessness of that first gut-bound alien. The original took place in space, where no one can hear you scream; in this film, no one can hear you scream above the deafening, kettle drum-bothering orchestral score.

The freaky-dystopian conspiracy spirit of 1970s sci-fi survives, sort of. At one point, someone produces a squeeze-box allegedly once owned by Stephen Stills, but doesn't actually play anything on it. But the subversive spirit has now been melded with the blander aesthetic of the top-dollar multiplex event movie. First time around, the ship was a claustrophobic confine whose crew would look tense and unwell in that stark uplight that seemed to beam off every work surface. Now, the characters are forever making excursions outside the ship into a colossal CGI alien landscape, a digital universe unavailable to Scott 30-odd years ago; although this world has a classical look, like the photorealist cover designs of strange crystalline worlds on SF paperbacks.

Prometheus is part prequel, part variation on a theme: the object is ostensibly to explain the presence in Alien of a strange humanoid-corpse with a hole blasted open in his stomach. This the film does get round to explaining, after many intestinal convolutions. What it also does is return us to the world of Erich von Däniken's 1968 bestseller Chariots of the Gods, about humankind being bred on Earth aeons ago by spaceman-aliens. The crew of the spacecraft Prometheus are basically on a mission in 2094 to establish this; no one mentions Von Däniken, perhaps not surprising as he has been pretty much forgotten even in 2012.

Ridley Scott and Noomi Rapace discuss making Prometheus Link to this video

Noomi Rapace is well cast as Dr Elizabeth Shaw, an intense and driven scientist who nonetheless has absorbed a calm religious faith from her father and always wears a cross around her neck. Her creationist views are never seriously challenged – except for one perfunctory complaint that she is going against "centuries of Darwinism" – and she is galvanised when, with her colleague and lover Dr Charlie Holloway (Logan Marshall-Green), she discovers ancient cave paintings in the Isle of Skye showing humans worshipping a specific star-constellation. Other cave paintings in the world duplicate this; astronomers find the constellation in question and soon, Dr Shaw and Dr Holloway are on board a spacecraft heading there, a mission bankrolled, in the time-honoured manner, by a shadowy corporation. Charlize Theron is the icy, black jumpsuit-clad corporate commander Meredith Vickers; Idris Elba is the rebellious captain, and there are some feisty, low-level tech guys.

Upstaging everyone is Fassbender, who provides the film's real glint of steel, while decentring its dramatic focus. He plays David, a robot who has been designed to look like a highly convincing humanoid, avowedly to avoid scaring or upsetting the crew. While they have been cryogenically frozen during the two-year flight, David has been gliding about like a head waiter keeping everything on board shipshape. But he is – again, more time-honoured tradition – a robot who might decide he has a mind of his own. Fassbender's David is blond; I think his eyelashes may be blond, too, and his English accent has a kind of refrigerated unctuousness. With his eerily Aryan look and stiff-armed walk, he's channelling C3PO and David Bowie's Man Who Fell to Earth. David also, like Wall-E, enjoys old movies, and he models his supercilious manner on Peter O'Toole in Lawrence of Arabia. As in other performances, Fassbender's lower jaw has a tendency to clench, as if suppressing rage or disgust: here it becomes an opaque, robotic mannerism of veiled threat.

When the crew land on that far-off planet, they make a staggering discovery, which for Dr Shaw is pretty much a conceptual orgasm, a moment of almost sexual congress with the unknown. Of course, her troubles begin when they return to the ship. The spacecraft on Alien had the Conradian title of Nostromo. (With his deployment of Lawrence of Arabia, Ridley Scott may also be hinting, at two or three removes, at David Lean's final unrealised plan to film Nostromo, and even be claiming some David Lean epic grandeur for himself.) Prometheus is the titan who was tortured by the gods for giving fire to the humans – but here it is the humans who are tortured and consumed by a new and terrible kind of fire.

It is a muddled, intricate, spectacular film, but more or less in control of all its craziness and is very watchable. It lacks the central killer punch of Alien: it doesn't have its satirical brilliance and its tough, rationalist attack on human agency and guilt. But there's a driving narrative impulse, and, however silly, a kind of idealism, a sense that it's exciting to make contact with whatever's out there.

Ridley Scott's return to the Alien universe is grandiose and muddled – with a scene-stealing Michael Fassbender performance

A kind of idealism … Prometheus.

Ridley Scott has counter-evolved his 1979 classic Alien into something more grandiose, more elaborate – but less interesting. In place of scariness there is wonderment; in place of tension there is hugely ambitious design; in place of unforgettable shocks there are reminders of the original's unforgettable shocks. There are also some shrewd and witty touches, and one terrifically creepy performance from Michael Fassbender, who steals the film with the chilling, parasitic relentlessness of that first gut-bound alien. The original took place in space, where no one can hear you scream; in this film, no one can hear you scream above the deafening, kettle drum-bothering orchestral score.

The freaky-dystopian conspiracy spirit of 1970s sci-fi survives, sort of. At one point, someone produces a squeeze-box allegedly once owned by Stephen Stills, but doesn't actually play anything on it. But the subversive spirit has now been melded with the blander aesthetic of the top-dollar multiplex event movie. First time around, the ship was a claustrophobic confine whose crew would look tense and unwell in that stark uplight that seemed to beam off every work surface. Now, the characters are forever making excursions outside the ship into a colossal CGI alien landscape, a digital universe unavailable to Scott 30-odd years ago; although this world has a classical look, like the photorealist cover designs of strange crystalline worlds on SF paperbacks.

Prometheus is part prequel, part variation on a theme: the object is ostensibly to explain the presence in Alien of a strange humanoid-corpse with a hole blasted open in his stomach. This the film does get round to explaining, after many intestinal convolutions. What it also does is return us to the world of Erich von Däniken's 1968 bestseller Chariots of the Gods, about humankind being bred on Earth aeons ago by spaceman-aliens. The crew of the spacecraft Prometheus are basically on a mission in 2094 to establish this; no one mentions Von Däniken, perhaps not surprising as he has been pretty much forgotten even in 2012.

Ridley Scott and Noomi Rapace discuss making Prometheus Link to this video

Noomi Rapace is well cast as Dr Elizabeth Shaw, an intense and driven scientist who nonetheless has absorbed a calm religious faith from her father and always wears a cross around her neck. Her creationist views are never seriously challenged – except for one perfunctory complaint that she is going against "centuries of Darwinism" – and she is galvanised when, with her colleague and lover Dr Charlie Holloway (Logan Marshall-Green), she discovers ancient cave paintings in the Isle of Skye showing humans worshipping a specific star-constellation. Other cave paintings in the world duplicate this; astronomers find the constellation in question and soon, Dr Shaw and Dr Holloway are on board a spacecraft heading there, a mission bankrolled, in the time-honoured manner, by a shadowy corporation. Charlize Theron is the icy, black jumpsuit-clad corporate commander Meredith Vickers; Idris Elba is the rebellious captain, and there are some feisty, low-level tech guys.

Upstaging everyone is Fassbender, who provides the film's real glint of steel, while decentring its dramatic focus. He plays David, a robot who has been designed to look like a highly convincing humanoid, avowedly to avoid scaring or upsetting the crew. While they have been cryogenically frozen during the two-year flight, David has been gliding about like a head waiter keeping everything on board shipshape. But he is – again, more time-honoured tradition – a robot who might decide he has a mind of his own. Fassbender's David is blond; I think his eyelashes may be blond, too, and his English accent has a kind of refrigerated unctuousness. With his eerily Aryan look and stiff-armed walk, he's channelling C3PO and David Bowie's Man Who Fell to Earth. David also, like Wall-E, enjoys old movies, and he models his supercilious manner on Peter O'Toole in Lawrence of Arabia. As in other performances, Fassbender's lower jaw has a tendency to clench, as if suppressing rage or disgust: here it becomes an opaque, robotic mannerism of veiled threat.

When the crew land on that far-off planet, they make a staggering discovery, which for Dr Shaw is pretty much a conceptual orgasm, a moment of almost sexual congress with the unknown. Of course, her troubles begin when they return to the ship. The spacecraft on Alien had the Conradian title of Nostromo. (With his deployment of Lawrence of Arabia, Ridley Scott may also be hinting, at two or three removes, at David Lean's final unrealised plan to film Nostromo, and even be claiming some David Lean epic grandeur for himself.) Prometheus is the titan who was tortured by the gods for giving fire to the humans – but here it is the humans who are tortured and consumed by a new and terrible kind of fire.

It is a muddled, intricate, spectacular film, but more or less in control of all its craziness and is very watchable. It lacks the central killer punch of Alien: it doesn't have its satirical brilliance and its tough, rationalist attack on human agency and guilt. But there's a driving narrative impulse, and, however silly, a kind of idealism, a sense that it's exciting to make contact with whatever's out there.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 7

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 9

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 638