I got here a collection (not full, that will be even more cases) of American nuke bombed themselves at homeland in history.

http://www.mercurynews.com/2013/09/...ed-wrench-socket-almost-incinerated-arkansas/

Book review: How a dropped wrench socket almost incinerated Arkansas

September 19, 2013 at 7:35 am

Today the world’s attention is focused on Damascus, Syria, and its chemical weapons. Thirty- three years ago events in Damascus, Ark. — also home to weapons of mass destruction — mesmerized the globe.

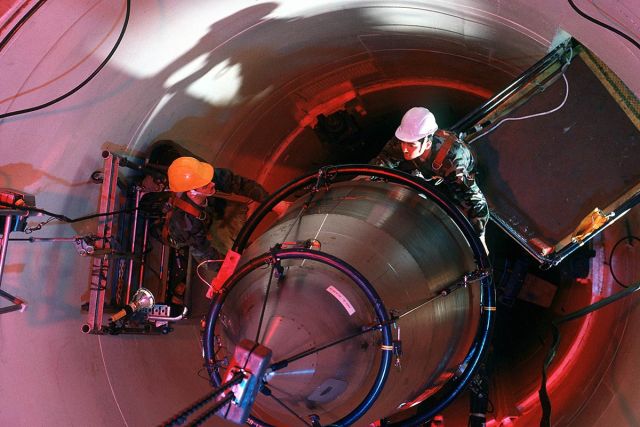

For almost nine hours starting on Sept. 18, 1980, brave airmen sought to contain the damage precipitated by a dropped wrench socket that hit a Titan II missile — which was tipped with a W-53 thermonuclear warhead — in its silo. The socket pierced the missile’s skin, causing fuel and oxidizer leaks.

The ensuing explosion destroyed the silo, propelling missile parts and warhead into abbreviated flight. One airman died from internal wounds while 21 personnel were injured. The W-53 warhead ended up on a nearby roadside — passed by motorists but fortunately never detonated. Close, but no mushroom cloud.

This freakish event is at the core of Eric Schlosser’s new book, “Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident and the Illusion of Safety.” “The United States has narrowly avoided a long series of nuclear disasters,” he writes.

The book makes clear that the U.S. has generally been good at handling its atomic weapons but has also had a lot of luck. He reveals declassified studies that disclose hundreds of mishaps between 1950 and ’67 and beyond. They include a B-61 hydrogen bomb accidentally dropped 7 feet from a parked B-52 bomber at Carswell Air Force Base in Texas, when a crewman pulled a handle too hard and a Mark 6 atomic bomb landing in a Mars Bluff, S.C., backyard, creating a 35-foot-deep crater and blowing out nearby windows and doors.

The 1980 Damascus incident unfolded against this background. The scary thing is that the Titan II explosion “was a normal accident, set in motion by a trivial event,” in this case a dropped socket, Schlosser says.

The book alternates between sections describing the accident with sections on the history of nuclear weapons in the U.S. Schlosser’s excellent eye for detail, which he displayed in his first book, “Fast Food Nation,” is also in evidence here.

He walks the reader — albeit sometimes in dense prose filed with PTS teams, RFHCO outfits, SRAM missiles and SIOP plans — through the post-World War II rivalries between civilian agencies and military services for control of the weapons. There were tensions between civilian technicians and scientists who pushed for safer devices and the military, who believed that safety often came at the expense of reliability.

I need to point out one historical misstep. In an abbreviated discussion of why the atomic bombs were dropped on Japan, Schlosser quotes a memo former President Herbert Hoover wrote to President Harry S. Truman that said an invasion could cost between “500,000 and 1 million American lives.”

But Schlosser doesn’t mention that War Secretary Henry Stimson asked a general to analyze Hoover’s memo, and was told that the estimate “was entirely too high.”

That incomplete reference aside, Schlosser takes Baby Boomers of the “duck and cover” era down a Megaton Memory Lane while providing a vivid primer for the Twitter generation on a world where nuclear weapons were a fact of life to deter a larger-than-life Soviet Union depicted as bent on world domination.

Some of the gems from “Command and Control”:

The Air Force Strategic Air Command public-relations machine allowed former bomber pilot Colonel Jimmy Stewart to film the 1955 “Strategic Air Command” on actual SAC bases after he met with cigar-chomping legend General Curtis LeMay.

Rhinelander, Wis., “became one of SAC’s favorite targets and it was secretly radar bombed hundreds of times thanks to the snow-covered terrain resembling that of the Soviet Union.”

The U.S. military at one point possessed 25 different types of nuclear weapons — ranging from missiles and warheads to the one-kiloton Mark 54 Special Atomic Demolition Munition “backpack bomb.”

As many as 17 states besides Arkansas had underground launch complexes — including Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Texas, South Dakota and Montana.

In a book devoted to scaring the hell out of the reader with tales of “accidents, miscalculations and mistakes,” Schlosser ends his epic pop history on a balanced note:

“One crucial fact must be kept in mind: none of the roughly 70,000 nuclear weapons built by the U.S. since 1945 has ever detonated inadvertently or without proper authorization” — a “remarkable achievement.”

Still, “thousands of missiles are hidden away, literally out of sight, topped with warheads and ready to go” — and “every one of them is an accident waiting to happen.”

“Command and Control” is published by Penguin Press, 632 pages, $36.

http://www.mercurynews.com/2013/09/...ed-wrench-socket-almost-incinerated-arkansas/

Book review: How a dropped wrench socket almost incinerated Arkansas

September 19, 2013 at 7:35 am

Today the world’s attention is focused on Damascus, Syria, and its chemical weapons. Thirty- three years ago events in Damascus, Ark. — also home to weapons of mass destruction — mesmerized the globe.

For almost nine hours starting on Sept. 18, 1980, brave airmen sought to contain the damage precipitated by a dropped wrench socket that hit a Titan II missile — which was tipped with a W-53 thermonuclear warhead — in its silo. The socket pierced the missile’s skin, causing fuel and oxidizer leaks.

The ensuing explosion destroyed the silo, propelling missile parts and warhead into abbreviated flight. One airman died from internal wounds while 21 personnel were injured. The W-53 warhead ended up on a nearby roadside — passed by motorists but fortunately never detonated. Close, but no mushroom cloud.

This freakish event is at the core of Eric Schlosser’s new book, “Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident and the Illusion of Safety.” “The United States has narrowly avoided a long series of nuclear disasters,” he writes.

The book makes clear that the U.S. has generally been good at handling its atomic weapons but has also had a lot of luck. He reveals declassified studies that disclose hundreds of mishaps between 1950 and ’67 and beyond. They include a B-61 hydrogen bomb accidentally dropped 7 feet from a parked B-52 bomber at Carswell Air Force Base in Texas, when a crewman pulled a handle too hard and a Mark 6 atomic bomb landing in a Mars Bluff, S.C., backyard, creating a 35-foot-deep crater and blowing out nearby windows and doors.

The 1980 Damascus incident unfolded against this background. The scary thing is that the Titan II explosion “was a normal accident, set in motion by a trivial event,” in this case a dropped socket, Schlosser says.

The book alternates between sections describing the accident with sections on the history of nuclear weapons in the U.S. Schlosser’s excellent eye for detail, which he displayed in his first book, “Fast Food Nation,” is also in evidence here.

He walks the reader — albeit sometimes in dense prose filed with PTS teams, RFHCO outfits, SRAM missiles and SIOP plans — through the post-World War II rivalries between civilian agencies and military services for control of the weapons. There were tensions between civilian technicians and scientists who pushed for safer devices and the military, who believed that safety often came at the expense of reliability.

I need to point out one historical misstep. In an abbreviated discussion of why the atomic bombs were dropped on Japan, Schlosser quotes a memo former President Herbert Hoover wrote to President Harry S. Truman that said an invasion could cost between “500,000 and 1 million American lives.”

But Schlosser doesn’t mention that War Secretary Henry Stimson asked a general to analyze Hoover’s memo, and was told that the estimate “was entirely too high.”

That incomplete reference aside, Schlosser takes Baby Boomers of the “duck and cover” era down a Megaton Memory Lane while providing a vivid primer for the Twitter generation on a world where nuclear weapons were a fact of life to deter a larger-than-life Soviet Union depicted as bent on world domination.

Some of the gems from “Command and Control”:

The Air Force Strategic Air Command public-relations machine allowed former bomber pilot Colonel Jimmy Stewart to film the 1955 “Strategic Air Command” on actual SAC bases after he met with cigar-chomping legend General Curtis LeMay.

Rhinelander, Wis., “became one of SAC’s favorite targets and it was secretly radar bombed hundreds of times thanks to the snow-covered terrain resembling that of the Soviet Union.”

The U.S. military at one point possessed 25 different types of nuclear weapons — ranging from missiles and warheads to the one-kiloton Mark 54 Special Atomic Demolition Munition “backpack bomb.”

As many as 17 states besides Arkansas had underground launch complexes — including Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Texas, South Dakota and Montana.

In a book devoted to scaring the hell out of the reader with tales of “accidents, miscalculations and mistakes,” Schlosser ends his epic pop history on a balanced note:

“One crucial fact must be kept in mind: none of the roughly 70,000 nuclear weapons built by the U.S. since 1945 has ever detonated inadvertently or without proper authorization” — a “remarkable achievement.”

Still, “thousands of missiles are hidden away, literally out of sight, topped with warheads and ready to go” — and “every one of them is an accident waiting to happen.”

“Command and Control” is published by Penguin Press, 632 pages, $36.