Beginning Again At Fifty-Five

In which I attempt to calculate the remaining years of my life and plan for the final act

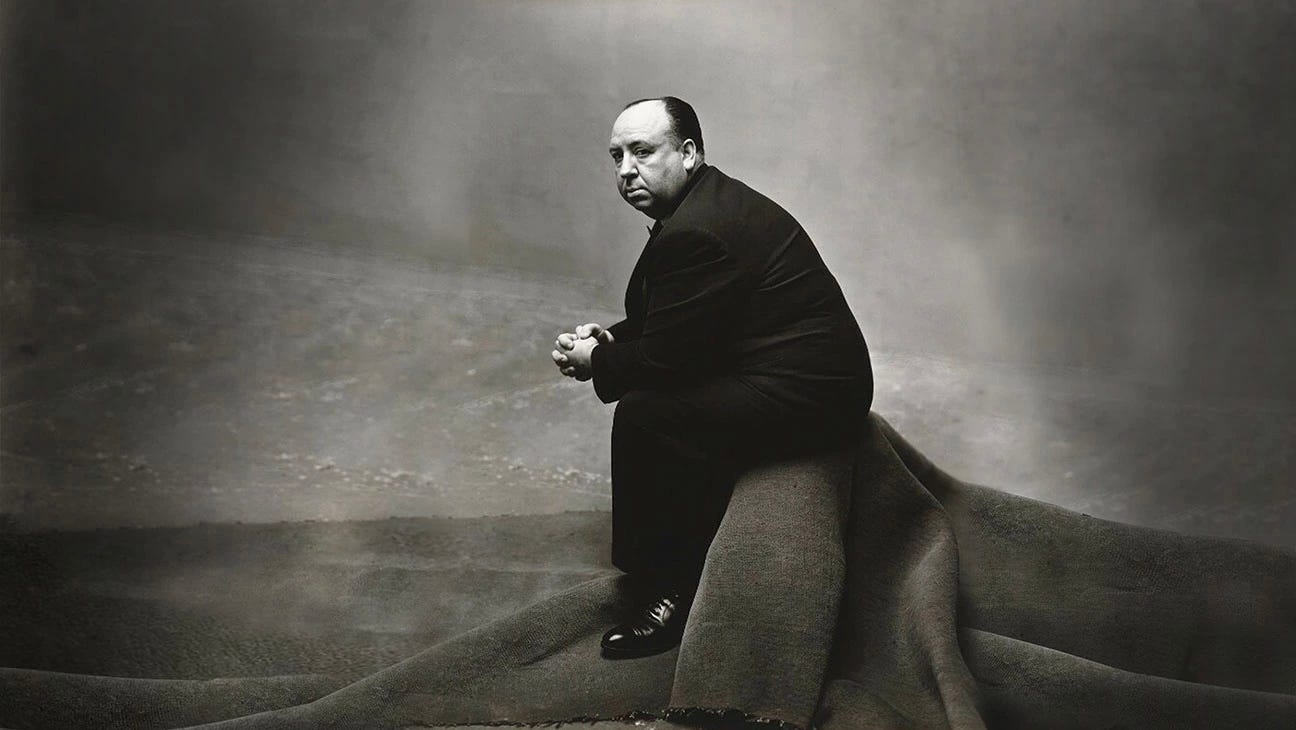

Self portrait of the author.

(Author’s note: Don’t be turned away too early in reading this piece. It starts a little dark but gets lighter as it goes. It ends with hope, as all good stories must.)

Today is my birthday. Monday, February 13. No need to make a fuss. I barely pay it any mind myself. I only bring it up because others do, and I thought I’d get out in front of it. My stepson Ricky stopped by earlier today and asked me when it was that I first felt old.

I had to think about it.

The average life expectancy in America for a white male is 77 years. By any reasonable calculation, at the unremarkable age of 55, I’m roughly three-quarters of the way through the only life I’m ever likely to experience. Three-quarters would technically be 57, but I’m hedging towards the lower side as I’m not the healthiest specimen walking the earth today. I’m not terribly motivated to do much to change that either, at least not drastically enough to prolong it much further. So, let’s call it a quarter left.

Whatever efforts I’m currently putting forth are the maximum expenditure I’m willing to do to not clock out too early, as in next week, month, or year. Assuming things go exceedingly well, I have about 20 years left to live. Give or take.

Your Gene Pool Depth Chart

It’s not exactly how Ricky asked the question, but that was the gist. When did I first realize I was old? He wasn’t so much suggesting I was old as trying to calculate how much time he had left himself. He followed his own rocky road as a young man and spent a lot of time walking paths that led nowhere.Age is a relative thing, despite our insistence on calculating the number of passes around the sun. Any sense of being old is less than concrete. We all know people who are old in their twenties, as well as 70-year-olds who put us all to shame. When I was Ricky’s age, I had already married his mother and was well on my way to achieving the American Dream of conspicuous consumption. He’s still single and slightly aimless in his career path. I fear he feels the scarcity of his remaining days more than most.

My mother is 80 and healthy but sometimes wonders aloud what she will be like when she’s old. At first, I thought that was incredibly funny, but now I’m with her. What will she be like when she’s old? She’s certainly not old yet, not to me anyway. She just got a new dog.

From a hereditary standpoint, I’m a bit split. My maternal grandfather died of heart failure when he was quite young, although not likely something he would die of today. Similarly, my paternal grandmother died of cancer long before she got old, an illness that would have been survivable today.

My remaining grandparents lived well into their 80s, and all were of sound mind. My paternal great-grandmother lived into her 90s, and I was fortunate to know her in my youth. She was sharp as a tack and lived alone almost until her death. When taken as an average, I suppose that’s a pretty good gene pool.

Feeling Your Age

I believe that you can consider yourself young all through your twenties. Once you hit thirty, you’re an adult with a budding family and actual responsibilities, but it’s your forties when you’re likely to hit peak economic success in your career. If you haven’t made it by then, you probably aren’t going to, despite the handful of celebrity outliers.Whether you’re a late bloomer or not, once you hit fifty, it’s pretty much all downhill. You’ll never again be the hot new thing at work, and your kids will likely have grown and moved out of your house.

I’m not saying life is over after fifty. If you so desire, there’s not much you can’t do if you want to badly enough. You’re not too old for most activities, but you’re not quite as spry as you once were; things stop operating as efficiently, nothing bends like it used to, and you begin to atrophy just a bit. You start to feel the effects of gravity. You do not bounce.

It’s not that you’re old, exactly, but that society no longer considers you young by any useful definition. You’re middle-aged at best. The Golden Girls were all in their 50s except the old one, one of their mothers. That’s where you are. That’s how the world sees you. Wise-cracking and cantankerous.

Once you’re in your fifties, you’re in the home stretch. If you go by averages, you have roughly another ten years of work left, assuming you don’t get put out to pasture too early. You might have to scrape around for consulting work or greeting people at a big box store for another five years, but after that, you can usually officially retire. Then you have about ten years until you croak. That’s assuming all goes well.

Money Can’t Buy Love, But It Does Buy Longevity

The quality of life in your later years has much more to do with wealth than genetics. If you come from money, you’re already ahead of the curve. You likely grew up with a healthy diet, easy access to healthcare, and quality education. That got you into a promising career where you made enough money to take care of yourself, and you probably have all your teeth.If you survive the stress of your high-profile career and whatever genetic skeletons are lurking in your family closet, you’ll be able to afford to see a doctor at the slightest sniffle and likely catch most treatable diseases early. Consequently, you’ll have gamed the system, and you’ll outlive your less fortunate peers.

If you were born poor, you still have a shot at winning the genetic lottery, but your chances of a long and healthy life are greatly diminished. You’re more likely to die early from poor diet, untreated medical issues, addiction, stress, or violence. Even if you manage to become wealthy by sheer grit and determination, your past might be too much to overcome.

The Midlife Crisis

They say that youth is wasted on the young. Nothing truer has ever been spoken. When we are young, we neglect beauty, destroy countless hours and even more brain cells, and abuse our bodies in unimaginable ways. Young people take unbelievable risks, as they are invincible, so consequently, not all make it to the second half, let alone the fourth quarter. But we all reach a point where the scarcity of our remaining days hits us like a brick. It’s a real bracer, I can tell you.This is when many people have what we like to call a midlife crisis. Although stories of men momentarily losing their minds, buying sports cars, divorcing their wives, and chasing younger women abound, men and women both deal with midlife crises equally.

“Though the term midlife crisis is fairly common,” writes Amy Capetta and Olivia Muenster, “it’s actually only existed since the mid-1960s, according to Psychology Today. Coined by psychologist Elliot Jacques, ‘midlife crisis’ was originally used to describe the period of life where adults tend to ‘reckon with their mortality.’ In other words, the phenomenon can be a little more complicated than how it’s often portrayed — it’s more than just someone purchasing a fancy car or picking up an unexpected hobby. As Baltimore-based therapist Dr. Heather Z. Lyons tells Woman’s Day, a midlife crisis, in essence, is a struggle with one’s own finiteness.”¹

A Crisis Of Confidence

A little more than a decade ago, I had a real crisis of confidence in my chosen career and, therefore, my purpose in life. I was ready to chuck it all and resign myself to being a starving artist. If I hadn’t been married, I probably would have done it, but I stuck it out and spent the next fifteen years in a cloud of alcohol, depression, anxiety, and desperation. I chased a few passions, such as photography and filmmaking but eventually realized they were no magic elixirs.But it was in my early fifties that I suddenly panicked that my life was nearly over and I hadn’t accomplished anything. I’d already chased all the women I wanted to and owned the sports cars. Like many aging men before, I became more fixated on leaving something behind. Some evidence that I had existed that might surpass my brief time here.

I’m still hoping for a third act to this tawdry tale. I believe that my remaining dreams are not only possible, but ultimately attainable. I may indeed die without having achieved my objectives, but until my last breath, I will continue to work towards my goals of infamy, trifling though they may be. As the years pass, my bucket list gets shorter, but the things on that list feel more like necessities than frivolities.

Old Masters and Young Geniuses

A few years ago, I was mowing the lawn and listening to a podcast by Malcolm Gladwell. He was talking about the research of David Galenson at the University of Chicago concerning different types of creative genius. Galenson was focused on the well-established presumption that most creative endeavors occurred in the early years of an artist. Youth produced the best art in a blaze of glory and then faded off into the sunset.“Genius, in the popular conception, is inextricably tied up with precocity,” writes Gladwell. “Doing something truly creative, we’re inclined to think, requires the freshness and exuberance and energy of youth. Orson Welles made his masterpiece, ‘Citizen Kane,’ at twenty-five. Herman Melville wrote a book a year through his late twenties, culminating, at age thirty-two, with ‘Moby-Dick.’ Mozart wrote his breakthrough Piano Concerto №9 in E-Flat-Major at the age of twenty-one.”²

Only that’s not what Galenson found at all. Yes, there were plenty of examples of youthful innovation, but also many instances of brilliance discovered later in life.

“Yes, there was Orson Welles, peaking as a director at twenty-five,” writes Gladwell. “But then there was Alfred Hitchcock, who made ‘Dial M for Murder,’ ‘Rear Window,’ ‘To Catch a Thief,’ ‘The Trouble with Harry,’ ‘Vertigo,’ ‘North by Northwest,’ and ‘Psycho’ — one of the greatest runs by a director in history — between his fifty-fourth and sixty-first birthdays. Mark Twain published ‘Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’ at forty-nine. Daniel Defoe wrote ‘Robinson Crusoe’ at fifty-eight.”³

‘My Name Is Alfred Hitchcock’ COURTESY OF HOPSCOTCH FILMS

Galenson decided there were two types of creatives that tended to produce our most lasting work. First, there are the conceptual innovators who “start with a clear idea of where they want to go, and then they execute it.” These are the Picasso’s of the world. The youthful genius who creates something new out of whole cloth in the blink of an eye.

Then there are the so-called late bloomers, the slow plodders, who Galenson calls experimental innovators. These are artists such as Cezanne, who toil their whole lives, experimenting and perfecting their ideas.⁴

“Experimental artists build their skills gradually over the course of their careers, improving their work slowly over long periods,” writes Galenson in his work Old Masters and Young Geniuses.⁵

Cramming For Finals

I’m a terrible procrastinator. It may be the one thing I really dislike about myself. It feels like a fundamental character flaw. To perpetually ignore something that needs doing. There’s not an inkling of logic to it. It will probably be the thing that ultimately does me in.The upside is that I work extremely well under pressure and can do the work of armies alone and in the blink of an eye. I don’t suffer from indecision. Once I know something has to be done, it’s done. Maybe it’s a side effect of my distaste for rules and schedules. Maybe it’s a pathetic attempt at control. Maybe it’s my fatal flaw.

But over the years, I’ve learned that there is no wasted time when I have a goal I’m committed to. I have moments of clarity where ideas come to me fully formed, but more often than not, I mull a problem over in my mind for as long as I’m allowed, and then I sit down, and I create. Once I sit down to do it, it all comes quickly because I’ve been working on it for hours, days, weeks, or months in my head. Once I’m ready, it just comes.

If I were to believe the hype, I might be tempted to think that I have wasted too much of my first 55 years of this life. But there might be another explanation, a more fully realized understanding of my life thus far. One in which I was gaining the life experience and writing skills needed to finally begin. I wasn’t ready.

Do I truly have only twenty years left, or do I have the incredible gift of every bit of twenty glorious years to complete the work I was put on this earth to do? Rather than seeing this as the end, I am choosing to see this as the beginning. All this time, I haven’t been wasting my time; I was experimenting. Learning, researching, failing, succeeding, and learning to avoid dead ends. I was sharpening my tools. I was preparing the way. I was getting ready.

Now, it’s time. Time to begin again.