Many said World War III has already started.

By BRANDON J WEICHERTFEBRUARY 23, 2023

Print

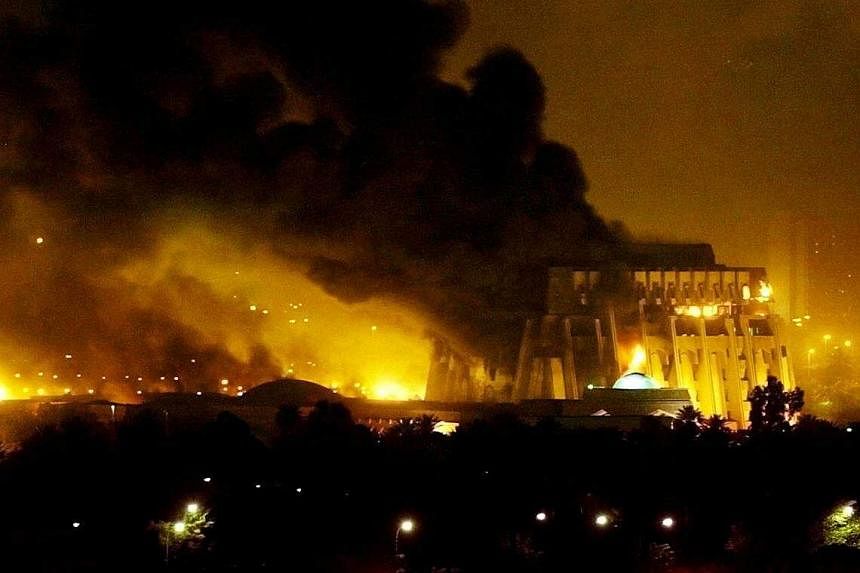

US President Joe Biden and Russian President Vladimir Putin have fumbled into a new world war. Photo: AFP / Mikhail Metzel / Sputnik

This past week will be remembered by most historians – if anyone is lucky enough to live through this Age of Self-Destruction – as the point of no return for the Russo-Ukrainian war.

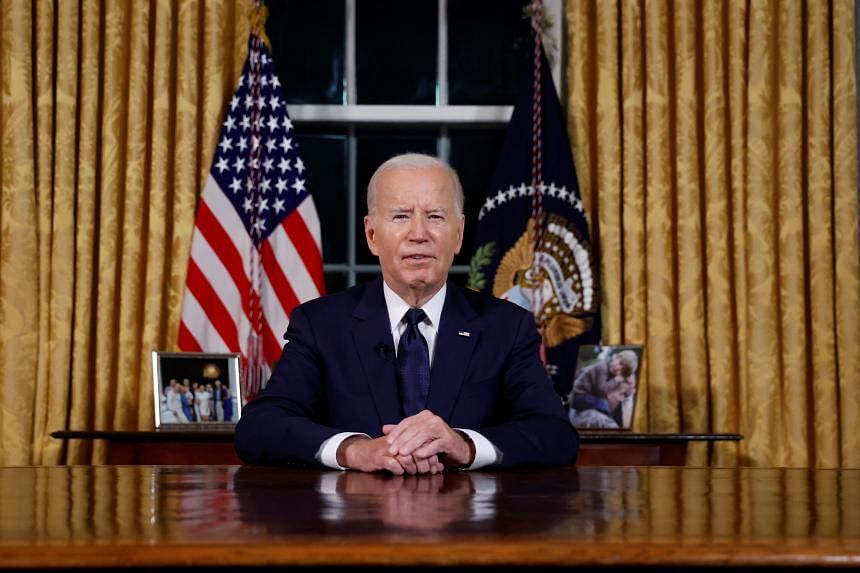

The world was treated (more like tormented) by dueling presidential speeches, one from the sclerotic US President Joe Biden, who journeyed to Kiev to reassert his undying support for Ukraine, the other by the surly Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Neither speech was particularly reassuring. Biden promised his Ukrainian wards an additional US$500 million in US taxpayer support for the besieged Ukrainians.

Shortly after his speech, the Pentagon hinted that it might stop slow-walking its promised (but as yet to be delivered) M1A2 Abrams main battle tank to the waiting arms of the desperate Ukrainian defenders and simply hand over the MBTs that are already in America’s warehouses (something that the Pentagon had resisted doing when the Biden administration made its initial announcement that it would, in fact, be sending the vaunted MBTs).

Unsurprisingly, most Western media outlets simply refused to cover the speech. Those few that did were openly derisive. The speech certainly was Castro-esque in its loquaciousness and was tinged with quasi-religious accusations against the West that would make most Iranian mullahs blush, but there was substance in Putin’s words.

He not only signaled that his commitment to the conflict was as strong as ever, but that he was escalating it, in response to what he viewed as an American escalation.

In fact, Putin issued his first significant threat toward the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO): He told his American rivals that they were to remove their offensive long-range weapons systems in Ukraine, otherwise Russian forces would begin directly targeting those systems.

A HIMARS missile launch. A combination of networked data and high-precision missiles has forced Russia to half its offensive in order to pivot to counter-battery missions. Photo: Asia Times file photo

Here is a red line that NATO and the Americans should think twice about crossing.

You see, these systems will be used by Ukraine to strike deep inside Russia. And while Ukraine certainly has a right to defend itself, the fact that it is doing so with capabilities that it only has thanks to the Americans means that the United States and NATO are now – in the eyes of Putin – direct combatants.

He said as much in his speech when he said the Americans will bear the responsibility for these actions should Russia be attacked by such systems.

What’s more, should these weapons systems be targeted by the Russians, one can anticipate that Americans will die. After all, just as with Russian S-400 emplacements in Syria, the American long-range systems are undoubtedly staffed or maintained at least partly by Americans.

Plus, there are likely American forces operating covertly in and around these long-range weapons systems, so we can expect that the Russian targeting of these systems and their surrounding environs will result in multiple American casualties.

The key takeaway from these two speeches that were delivered hours apart from each other is that there is now no hope for a peace deal.

Of course, the New START Treaty did confer several decisive advantages on to the Russian side when the deal was signed by former president Barack Obama and former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev (with Putin’s blessing).

Still, Russia has a long history of supporting a coterie of arms-control agreements with the Americans going back to the heady Cold War days.

For Putin to pull Russia out of an agreement of which he was a vociferous defender should raise hairs on the backs of the necks of Washington policymakers. Yet all these statements have done is to harden Washington’s zeal in blindly supporting its Ukrainian proxy.

Putin’s decision to withdraw from the treaty speaks to the depths that he is willing to go to ensure that he wins this war. Thus compromise is not possible at this rate. The only thing that would make a peace deal tenable for Russia would be if its military were decisively defeated.

Peace activists wearing masks of Russian President Vladimir Putin and US President Joe Biden pose with mock nuclear missiles in front of the US Embassy in Berlin on January 29, 2021, in an action to call for more progress in nuclear disarmament. Photo: AFP / John MacDougall

While the Russians have certainly taken heavy losses, Ukraine has also taken significant losses lately. Unlike the Ukrainians, the Russians can afford to keep sending hundreds of thousands of their people into the meat grinder until they simply attrit the Ukrainians; until Russia’s larger forces bleed Ukraine’s forces dry in the field – and then surge over their corpses. This, at least, appears to be the general Russian plan.

If necessary, Putin will deploy tactical nuclear weapons to ensure that his forces can accomplish this herculean task.

That too is a red line that if crossed will likely trigger Moscow into risking nuclear war. Russia cannot lose its naval base in Sevastopol. If it does, it ceases being a major power, as it is isolated away from the vital Black Sea region.

The West is living in a pure fantasy if its so-called leadership thinks that Putin will simply sit back and watch this unfold. That was the point of Putin’s long-winded speech. The war isn’t ending. There will be no negotiated settlement (at least not one any time soon, or one that favors the Western side).

For his part, Biden made clear that he was not only going to continue his support for President Volodymyr Zelensky’sgovernment of Kiev. Biden further tweeted upon his departure from Kiev that he had “left a part of his heart” there.

How nice.

Biden is so committed to the Ukrainian cause that he has thus far refused to respond adequately to the major chemical spill in East Palestine, Ohio, which has been dubbed by many critics of Biden as “America’s Chernobyl.”

Biden has instead lavishly doled US tax dollars out to a foreign country, Ukraine, instead of fellow Americans suffering in that disaster zone – in what is likely the run-up to his re-election campaign for president.

If that doesn’t show you how far Biden is willing to go for Ukraine, I don’t know what will.

Why would Russia seek peace if the war is turning in its favor, as it is?

Rather than a deal being hatched, another world war is at hand, made possible by the combined arrogance and ignorance of both Western and Russian leaders, who’ve miscalculated from the very beginning to the ultimate end of this conflict.

Just as with the First World War, of course, there will be no victors here.

If it plays its strategic cards right, though, the Communist Party of China will benefit greatly from seeing its two greatest strategic competitors, Russia and America, devour each other over a senseless border dispute in southern Europe (which is why Beijing is likely supporting Russia in its fight in Ukraine).

Chinese President Xi Jinping on a large screen during a cultural performance as part of the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China on June 28, 2021. Photo: AFP / Noel Celis

Historians will look back with confusion as to how idiotic the leaders of this time were. They will note that the two speeches of the Russian and American presidents on the one-year anniversary of the start of the Russo-Ukrainian war was the moment in which the conflict truly became a world war.

What’s more, they will wonder how a people blessed with so much could have been so irresponsible as to throw it all away for a petty dispute.

Face it, there will be no peace in our time. The recent speeches made by Biden and Putin, as well as the increasing involvement of China in the Ukraine conflict, mean that war is our lot – and this war is not one that the West can easily win.

Brandon J Weichert is a former US congressional staffer and a geopolitical analyst. On top of being a contributor at Asia Times, he is a contributing editor at American Greatness and The Washington Times. Weichert recently became a senior editor at 19FortyFive. He is the author of Winning Space: How America Remains a Superpower, The Shadow War: Iran’s Quest for Supremacy, and Biohacked: China’s Race to Control Life. He can be followed via Twitter @WeTheBrandon. More by Brandon J Weichert

World War III is already here

Historians will look back with confusion as to how idiotic the leaders of this time wereBy BRANDON J WEICHERTFEBRUARY 23, 2023

US President Joe Biden and Russian President Vladimir Putin have fumbled into a new world war. Photo: AFP / Mikhail Metzel / Sputnik

This past week will be remembered by most historians – if anyone is lucky enough to live through this Age of Self-Destruction – as the point of no return for the Russo-Ukrainian war.

The world was treated (more like tormented) by dueling presidential speeches, one from the sclerotic US President Joe Biden, who journeyed to Kiev to reassert his undying support for Ukraine, the other by the surly Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Neither speech was particularly reassuring. Biden promised his Ukrainian wards an additional US$500 million in US taxpayer support for the besieged Ukrainians.

Shortly after his speech, the Pentagon hinted that it might stop slow-walking its promised (but as yet to be delivered) M1A2 Abrams main battle tank to the waiting arms of the desperate Ukrainian defenders and simply hand over the MBTs that are already in America’s warehouses (something that the Pentagon had resisted doing when the Biden administration made its initial announcement that it would, in fact, be sending the vaunted MBTs).

Understanding Putin’s speech

The other speech came from Putin, who spoke for a whopping two hours on Tuesday evening, in which he reiterated his commitment to total victory over Ukraine and how the United States was ruled by “satanists” and “pedophiles.”Unsurprisingly, most Western media outlets simply refused to cover the speech. Those few that did were openly derisive. The speech certainly was Castro-esque in its loquaciousness and was tinged with quasi-religious accusations against the West that would make most Iranian mullahs blush, but there was substance in Putin’s words.

He not only signaled that his commitment to the conflict was as strong as ever, but that he was escalating it, in response to what he viewed as an American escalation.

In fact, Putin issued his first significant threat toward the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO): He told his American rivals that they were to remove their offensive long-range weapons systems in Ukraine, otherwise Russian forces would begin directly targeting those systems.

A HIMARS missile launch. A combination of networked data and high-precision missiles has forced Russia to half its offensive in order to pivot to counter-battery missions. Photo: Asia Times file photo

Here is a red line that NATO and the Americans should think twice about crossing.

You see, these systems will be used by Ukraine to strike deep inside Russia. And while Ukraine certainly has a right to defend itself, the fact that it is doing so with capabilities that it only has thanks to the Americans means that the United States and NATO are now – in the eyes of Putin – direct combatants.

He said as much in his speech when he said the Americans will bear the responsibility for these actions should Russia be attacked by such systems.

What’s more, should these weapons systems be targeted by the Russians, one can anticipate that Americans will die. After all, just as with Russian S-400 emplacements in Syria, the American long-range systems are undoubtedly staffed or maintained at least partly by Americans.

Plus, there are likely American forces operating covertly in and around these long-range weapons systems, so we can expect that the Russian targeting of these systems and their surrounding environs will result in multiple American casualties.

The key takeaway from these two speeches that were delivered hours apart from each other is that there is now no hope for a peace deal.

Speeding toward nuclear war

Putin made the shocking announcement that Russia was withdrawing from the Obama-era New START Treaty, which limited the number of tactical nuclear weapons that both the United States and Russia could have.Of course, the New START Treaty did confer several decisive advantages on to the Russian side when the deal was signed by former president Barack Obama and former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev (with Putin’s blessing).

Still, Russia has a long history of supporting a coterie of arms-control agreements with the Americans going back to the heady Cold War days.

For Putin to pull Russia out of an agreement of which he was a vociferous defender should raise hairs on the backs of the necks of Washington policymakers. Yet all these statements have done is to harden Washington’s zeal in blindly supporting its Ukrainian proxy.

Putin’s decision to withdraw from the treaty speaks to the depths that he is willing to go to ensure that he wins this war. Thus compromise is not possible at this rate. The only thing that would make a peace deal tenable for Russia would be if its military were decisively defeated.

Peace activists wearing masks of Russian President Vladimir Putin and US President Joe Biden pose with mock nuclear missiles in front of the US Embassy in Berlin on January 29, 2021, in an action to call for more progress in nuclear disarmament. Photo: AFP / John MacDougall

While the Russians have certainly taken heavy losses, Ukraine has also taken significant losses lately. Unlike the Ukrainians, the Russians can afford to keep sending hundreds of thousands of their people into the meat grinder until they simply attrit the Ukrainians; until Russia’s larger forces bleed Ukraine’s forces dry in the field – and then surge over their corpses. This, at least, appears to be the general Russian plan.

If necessary, Putin will deploy tactical nuclear weapons to ensure that his forces can accomplish this herculean task.

No turning back

The Ukrainians have made their intentions clear since before the conflict erupted a year ago: Kiev wants the complete restoration of Crimea and, eventually, eastern Ukraine.That too is a red line that if crossed will likely trigger Moscow into risking nuclear war. Russia cannot lose its naval base in Sevastopol. If it does, it ceases being a major power, as it is isolated away from the vital Black Sea region.

The West is living in a pure fantasy if its so-called leadership thinks that Putin will simply sit back and watch this unfold. That was the point of Putin’s long-winded speech. The war isn’t ending. There will be no negotiated settlement (at least not one any time soon, or one that favors the Western side).

For his part, Biden made clear that he was not only going to continue his support for President Volodymyr Zelensky’sgovernment of Kiev. Biden further tweeted upon his departure from Kiev that he had “left a part of his heart” there.

How nice.

Biden is so committed to the Ukrainian cause that he has thus far refused to respond adequately to the major chemical spill in East Palestine, Ohio, which has been dubbed by many critics of Biden as “America’s Chernobyl.”

Biden has instead lavishly doled US tax dollars out to a foreign country, Ukraine, instead of fellow Americans suffering in that disaster zone – in what is likely the run-up to his re-election campaign for president.

If that doesn’t show you how far Biden is willing to go for Ukraine, I don’t know what will.

No peace in our time

Beijing is now getting involved more directly on the side of Moscow, meaning that Russia will have greater maneuvering room at a time when the West desperately needs the Russians to be isolated.Why would Russia seek peace if the war is turning in its favor, as it is?

Rather than a deal being hatched, another world war is at hand, made possible by the combined arrogance and ignorance of both Western and Russian leaders, who’ve miscalculated from the very beginning to the ultimate end of this conflict.

Just as with the First World War, of course, there will be no victors here.

If it plays its strategic cards right, though, the Communist Party of China will benefit greatly from seeing its two greatest strategic competitors, Russia and America, devour each other over a senseless border dispute in southern Europe (which is why Beijing is likely supporting Russia in its fight in Ukraine).

Chinese President Xi Jinping on a large screen during a cultural performance as part of the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China on June 28, 2021. Photo: AFP / Noel Celis

Historians will look back with confusion as to how idiotic the leaders of this time were. They will note that the two speeches of the Russian and American presidents on the one-year anniversary of the start of the Russo-Ukrainian war was the moment in which the conflict truly became a world war.

What’s more, they will wonder how a people blessed with so much could have been so irresponsible as to throw it all away for a petty dispute.

Face it, there will be no peace in our time. The recent speeches made by Biden and Putin, as well as the increasing involvement of China in the Ukraine conflict, mean that war is our lot – and this war is not one that the West can easily win.

Brandon J Weichert is a former US congressional staffer and a geopolitical analyst. On top of being a contributor at Asia Times, he is a contributing editor at American Greatness and The Washington Times. Weichert recently became a senior editor at 19FortyFive. He is the author of Winning Space: How America Remains a Superpower, The Shadow War: Iran’s Quest for Supremacy, and Biohacked: China’s Race to Control Life. He can be followed via Twitter @WeTheBrandon. More by Brandon J Weichert