Ukraine’s Leader Flees Palace as Protesters Widen Control

By ANDREW HIGGINS and ANDREW E. KRAMER FEB. 22, 2014

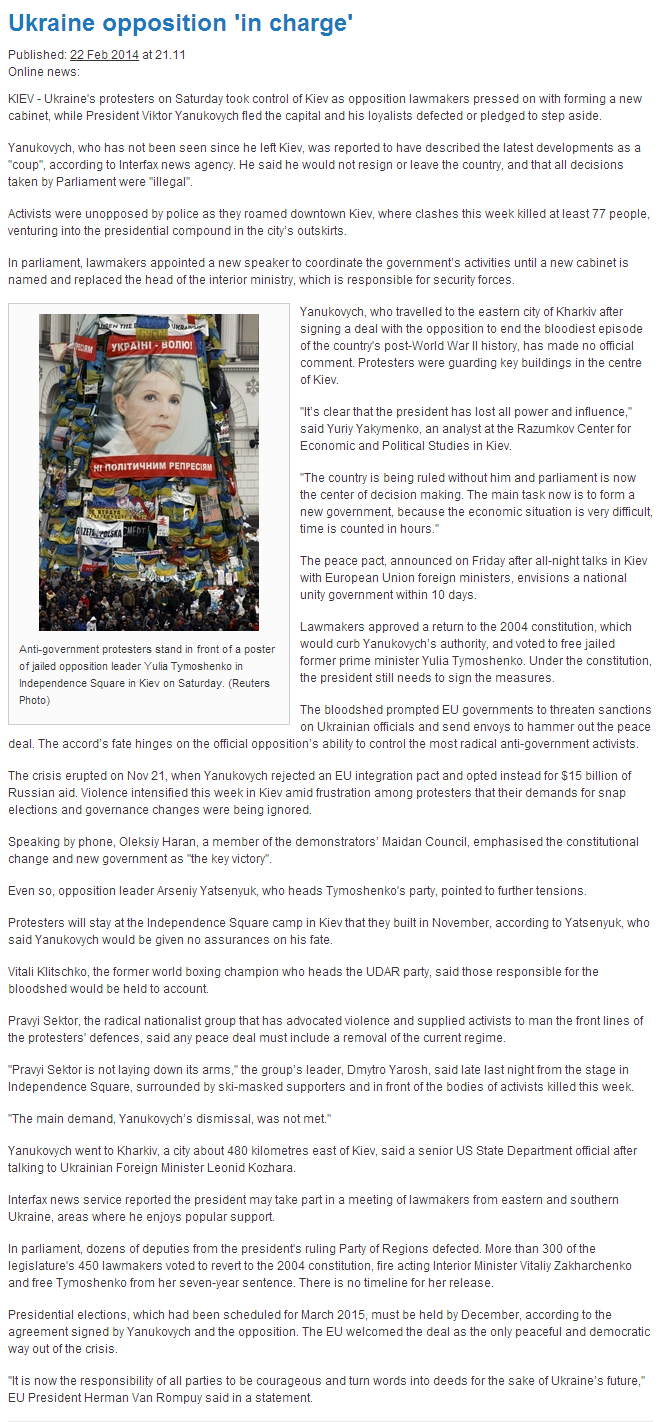

Protesters at the residence of Ukraine’s president, Viktor F. Yanukovych, which was seized and open to the public in Kiev, Ukraine, on Saturday. Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

KIEV, Ukraine — Opposition leaders took control of the presidential palace outside Kiev on Saturday, as Ukraine’s president, Viktor F. Yanukovych, fled the capital and Parliament, beginning to chart what appeared to be a new course for the former Soviet republic, called for elections to replace him.

Members of an opposition group from Lviv called the 31st Hundred — carrying clubs and some of them wearing masks — were in control of the entryways to the palace Saturday morning. They watched as thousands of citizens strolled through the grounds during the day, gazing in wonder at the mansions, zoo, golf course, enclosure for rare pheasants and other luxuries, set in a birch forest on a bluff soaring above the Dnepr River.

Protesters in Kiev, the Ukrainian capital, where growing numbers of right-wing street groups have clashed with the police.Converts Join With Militants in Kiev ClashFEB. 20, 2014

“This commences a new life for Ukraine,” said Roman Dakus, a protester-turned-guard, who was wearing a ski helmet and carrying a length of pipe as he blocked a doorway. “This is only a start,” he added. “We need now to make a new structure and a new system, a foundation for our future, with rights for everybody, and we need to investigate who ordered the violence.”

Despite Accord, Tensions Continue in KievUriel Sinai for The New York Times

Mr. Yanukovych appeared on television Saturday afternoon, saying that he had been forced to leave the capital because of a “coup,” and that he had not resigned, and did not plan to. He said he understood that people had suffered in recent days. “I feel pain for my country,” he said. “I feel responsibility. I will keep you informed of what we will do further, every day.”

He also said that he was traveling to the southeastern part of the country to talk to his supporters — a move that carried potentially ominous overtones, in that the southeast is the location, among other things, of the Crimea, the historically Russian section of the country where a Russian naval base is located.

But Parliament subsequently declared Mr. Yanukovych unable to carry out his duties and set a date of May 25 to elect his replacement.

An image taken from television provided by the Presidential Press Service showed Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych speaking in Kharkiv on Saturday. Presidential Press Service, via Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

A spokeswoman for the imprisoned opposition leader and former prime minister, Yulia V. Tymoshenko, said Ms. Tymoshenko would be released within hours from the prison hospital in eastern Ukraine where she was being held.

Protesters said they had seen helicopters and cars leaving the palace compound Friday night and Saturday morning, and Mr. Yanukovych said that his car had been fired upon.

With political authority having collapsed, protesters claimed to have established control over Kiev. By Saturday morning they had secured key intersections of the city and the government district of the capital, which police officers had fled, leaving behind burned military trucks, mattresses and heaps of garbage at the positions they had occupied for months.

Yevgenia Tymoshenko, center, reacted as the Parliament voted to free her mother, Ukrainian opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko, during a session in Kiev, Ukraine, on Saturday. Andrii Skakodub/Reuters

In Parliamentopposition members began laying the groundwork for a change in leadership, electing Oleksander Turchynov, an ally of Ms. Tymoshenko, as speaker.

Underscoring the volatility of the situation and the potential power vacuum, Oleg Tyagnibok, the leader of the nationalist Svoboda party, asked the country’s interior minister and “forces on the side of the people” to patrol the capital to prevent looting.

On Friday Mr. Yanukovych and opposition leaders, with the help of France, Germany, Poland and Russia, ,had reached an accord that reduced the power of Mr. Yanukovych, an ally of Moscow. But Russia then refused to sign the accord, stirring fears that Moscow might now work to undo the deal through economic and other pressures, as it did last year to subvert a proposed trade deal between Ukraine and the European Union. But American officials said that President Vladimir V. Puton told Mr. Obama in a telephone call on Friday that he would work toward resolving the crisis.

Oksana Solchanyk, center, her husband, Zinovij, left, and son Stepan mourned on Saturday in Lviv, Ukraine, over the body of their son and brother, Bohdan, 28, who was killed in Kiev during anti-government protests. Uriel Sinai for The New York Times

The developments cast a shadow over the hard-fought accord reached that also mandates early presidential elections by December, a swift return to a 2004 Constitution that sharply limited the president’s powers and the establishment within 10 days of a “government of national trust.”

In a series of votes that followed the accord and reflected Parliament’s determination to make the settlement work, lawmakers moved to free Ms. Tymoshenko; grant blanket amnesty to all antigovernment protesters; and provide financial aid to the hundreds of wounded and families of the dead.

Except for a series of loud explosions on Friday night and angry chants in the protest encampment, Kiev was generally quiet with the streets largely calm on Saturday. And the authorities, although previously divided about how to handle the crisis, seemed eager to avoid more confrontations.

Sergey Ponomarev for The New York TimesKiev: Triage in Crisis In the Ukrainian capital, triage centers have sprung up around Independence Square, where dozens of people have died in the fighting.

In Independence Square, the focal point of the protest movement, however, the mood was one of deep anger and determination, not triumph. “Get out criminal! Death to the criminal!” the crowd chanted, reaffirming what, after a week of bloody violence, has become a nonnegotiable demand for many protesters: the immediate departure of Mr. Yanukovych.

When Vitali Klitschko, one of three opposition leaderswho signed the deal to end the violence, spoke in its defense, people screamed “shame!” A coffin was then hauled on a stage in the square to remind Mr. Klitschko of the more than 70 people who died in violence on Thursday, the deadliest day of political mayhem in Ukraine since independence from the Soviet Union more than two decades ago.

The violence escalated the urgency of the crisis, which began with protests in late November after a decision by Mr. Yanukovych to spurn a trade and political deal with the European Union and tilt his nation toward Russia instead.

It was difficult to know how much of the fury voiced on Friday night in Independence Square was fiery bravado, a final cry of anger before the three-month-long protest movement winds down or the harbinger of yet more and possibly worse violence to come.

Vividly clear, however, was the wide gulf that had opened up between the opposition’s political leadership and a street movement that has radicalized and slipped far from the already tenuous control of politicians.

Mr. Klitschko was interrupted by an angry radical who did not give his name but said he was the leader of a group of fighters, known as a hundred.

Former Ukrainian prime minister and opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko in Kiev in 2011. Sergey Dolzhenko/European Pressphoto Agency

“We gave chances to politicians to become future ministers, presidents, but they don’t want to fulfill one condition — that the criminal go away!” he said, vowing to lead an armed attack if Mr. Yanukovych did not announce his resignation by 10 a.m. on Saturday. The crowd shouted: “Yes! Yes!”

Dmytro Yarosh, the leader of Right Sector, a coalition of hard-line nationalist groups, reacted defiantly to news of the settlement, drawing more cheers from the crowd.

“The agreements that were reached do not correspond to our aspirations,” he said. “Right Sector will not lay down arms. Right Sector will not lift the blockade of a single administrative building until our main demand is met — the resignation of Yanukovych.”

He added that he and his supporters were “ready to take responsibility for the further development of the revolution.” The crowd shouted: “Good! Good!”

By early afternoon, the presidential compound of brick paved pathways, beautifully landscaped in hedges, and all set in a birch forest on a bluff overlooking the Dnepr River, was filled with hundreds of people. Some outbuildings were open; men carrying ax handles and other clubs guarded the entrances to others, lest looting begin. Around noon gunshots or explosions rang out but it was unclear what had happened.

One member of the Lviv Hundred walked onto a gazebo decorated with plastic urns, removed his green military helmet and gazed out at the park and the river below.

Another pair in soot-smeared clothing and carrying baseball bats walked into an outbuilding apparently used for summer barbecues, and sat in chairs of plush blue and gold upholstery decorated in a floral print. They pulled large yellow drinking glasses from a cabinet and photographed one another on their cellphones as if saying toasts.

“We hoped for this but didn’t expect it,” said Roman Dakus, wearing a ski helmet and carrying a length of pipe, who guarding one doorway. He had been in Independence Square, known as Maidan, off and on for three months, he said. “It was very, very difficult to stay on the square in the cold at night,” he said. “But we warmed one another with our hearts and our souls.”

“This commences a new life for Ukraine,” he said, waving his pipe to take in the overrun presidential residence. “People really changed their mind-set because of these events. Before, people thought, ‘Nothing really depends on me.’ They preferred to say that and to think like that. But after this situation, they think differently. They believe in their struggle when they are all together.”