Must excerpt then can read:

Kirsten Han

I'm a Singaporean freelance journalist and writer. I'm happiest writing about social justice and human rights issues, wherever they may be in the world.

Oct 20

The Silhouette of Oppression

There are parts of the world where journalism is a frightening, dangerous job. Arrests, detention, kidnappings, even murder. Singapore isn’t one of those places. Yet the Southeast Asian nation

ranks 151st in the latest World Press Freedom Index — below Myanmar, Russia and Zimbabwe—and many citizens consider political journalism a “scary” endeavour. Somewhere along the trajectory of his or her life, the average Singaporean has picked up the belief that politics — being involved in it, having opinions about it, commenting on it — is scary, risky somehow. “Things happen” to people who stick their necks out.

The same political party has ruled Singapore for over 50 years. It’s brought stability and uninterrupted, long-term plans that make political decisions seem like inevitabilities rather than negotiations. We’re told that this is part of our secret to success; why seek challenge and dissent, when things can be so much simpler?

Do you want more democracy, with its mess and chaos and ugly disagreements, or do you want efficiency, peace and economic growth? It’s better this way, we’re told.

We believe it, for the most part. We believe it because it’s easier to believe than to challenge. Life is comfortable here; a humid tropical blip on the Equator turned cool with air-conditioning in glass malls containing everything you need to enjoy life. The streets are clean, the public transport (relatively) reliable, the city safe enough to leave one’s bag unattended while buying drinks in a food court. The WiFi is fast and mobile networks work even in tunnels.

Singapore’s development and wealth makes it easy to mistaken modernity for freedom.

Access to these modern conveniences makes it easier to be satisfied with the status quo. It’s difficult to believe oppression happens in such privileged “First World” environs. The cafés with rainbow cakes, the queues for the latest iPhone, the rows of designer boutiques in posh shopping centres don’t fit the image of authoritarian states we tend to have: all grey and angular, with visible police patrols and dissidents grabbed off the streets.

Yet there’s an exchange that I have over and over with Singaporeans. An instance that stuck in my mind was with the middle-aged manager of a food stall.

“Journalism is tough, right?” he said as he counted out my change. “I guess if you don’t write about politics here it’s not too bad…”

“Oh, I do write about politics.”

His eyebrows shot up above his glasses. “But that’s so tough!” he exclaimed. “If you write the truth you get in trouble, but if you don’t no one reads it because you’re a liar.”

Or the time with a private-hire driver who, after hearing about my work, commented, “What a dangerous life you lead.”

This internalised fear isn’t all paranoia; there’s a history behind this cautious nervousness, a story obscured through a neat manipulation of the narrative, but whose shadow lives on in the half-hidden recesses of a national consciousness.

The police came bashing on doors in the early hours of the morning in the late 1980s. They searched homes, confiscated books, took people away. Decades later these former detainees tell of interrogations and intimidation that sound more like excerpts of an Orwellian novel than real life.

“Standing barefoot beneath the blast of the air-conditioner without having taken breakfast, and with just three hours of sleep, I shivered and thought of how best to keep warm. … There was one male officer who came in and shouted something. My answer did not satisfy him or rather he was not prepared to be convinced. He gave me four hard slaps… The slaps sent a gush of hot blood to my face,” wrote former detainee Teo Soh Lung in her

memoirs.

The national broadsheet printed statements from the government verbatim. They told the nation these people were Marxists seeking to overthrow the state. “Confessions” were televised, social workers, lawyers, Catholics cast as threats to national security.

The message to Singapore’s tiny civil society circle was clear:

This is what can happen. This is what we can do.Activism and dissent became muted for years, disrupting the continuity of a resistance that was itself a tentative resumption of an earlier era of political activity and community organising.

This is a part of our collective past that we do not discuss. It isn’t mentioned in textbooks, nor does it feature in the Internal Security Department’s Heritage Centre, where visits are by special arrangement only. We laud the achievements of our small country over and over again every National Day as a massive flag — suspended between Chinook helicopters — flies around the island, but we won’t mention the detention of our fellow citizens, with neither charge nor trial. Although it happened not so long ago, most young Singaporeans won’t have heard of the operation’s codename, Spectrum, nor will they be able to name the detainees who wasted their days away in drab cells.

Once in awhile, though, there will be reminders of this power. A blogger sued and made to

pay tens of thousands in damages to the prime minister. A teenager arrested and

jailed for rude comments about religions. Contempt of court

chargesbrought against individuals and

fines doled out. Arrests of

protestersand

artists, even if they had been acting alone and not disruptive.

These moves strike that hidden chord within Singaporean psyches and provide a reminder:

This is what can happen. This is what we can do. But there’ll always be a reason for these arrests and lawsuits and investigations. There’ll always be some law or regulation the authorities can point to. There’ll always be some justification for the credulous:

no, this isn’t oppression, we’re just enforcing the rules.

The result is a bizarre contradiction: a country whose citizens instinctively know that some things cannot be said or done — not without repercussion, anyway — even while oppression itself seems distant and unreal.

When people tell me that my job is dangerous, it stems from a belief that political work is akin to wandering ever closer to an electric fence. But is the fence really live, and what happens if you touch it? That, they can never quite say.

In my early years as a blogger and activist in Singapore, I found these reactions strange, and a little overblown. I was aware of the history of oppression and the climate of fear in which Singaporeans operated, but couldn’t quite imagine anything happening to

me.

My first time speaking in Hong Lim Park in 2010. (Photo: We Believe in Second Chances)

“You should be careful. Think of your family,” people said whenever they read a contentious piece or heard about my involvement in activities at Hong Lim Park — the only place in the entire country where citizens can assemble for a cause without permission from the authorities.

I’d choose not to argue, but also not to listen. The thought of getting arrested, thrown in jail or bankrupted seemed incongruous with my everyday reality: dining in restaurants, watching movies, online shopping and complaining about the heat. I didn’t fit my personal casting call for “person of interest”, nor did Singapore fulfil the Hollywood-esque mental image of “oppressive state”. It seemed outlandish to imagine that I would be important enough to warrant any attention, or that the state would be sensitive or petty enough to make things difficult for me or my loved ones.

That was seven years ago. Singapore is still a good place to live. I still enjoy evenings out with my friends, air-conditioning in my flat and bubble tea whenever I want it. But I’ve also learnt that there are many ways to exercise power and exert control.

There is no freedom of information in Singapore, and many procedures and processes happen in black boxes with little transparency. Visas and jobs can be denied with no reasons given, thus restricting methods and grounds for appeal. Legislation is worded broadly enough for all sorts of activity to fall within its confines. Opportunities can vanish in circumstances that are just enough to trigger suspicions, but not verify anything. Only once in a while will someone come across a tidbit that suggests interference, whether from the Internal Security Department or elsewhere, but even these crumbs can be difficult to document, whispered as they are in off-record conversations with no paper trail.

It’s no longer a sinister knocking on your door in the early hours of the morning, nor is it a session in a freezing interrogation room. It’s neither a show trial nor a bullet to the chest, as faced by human rights defenders elsewhere in the world. With little explanation or warning, the bottom simply falls out for some people, pieces of their lives bent out of shape without anyone knowing how they can be fixed.

When these things happen, there are never any answers, only questions. No one will confirm that your critiques of the state lost you your shot at tenure. No one will explain that your visa or job application hit a snag because of your involvement in activism. No one will provide you with such certainty… but you will wonder about nothing else. You, and the people around you, will reach the conclusion that there can be no other explanation.

But herein lies the masterstroke. You’ve concluded that you’ve fallen victim to reprisal or repression, and everyone you know agrees. But you’ll still hesitate to make this claim public, because you know that when the demand for proof comes, you’ll have none. It’s oppression and cover-up all at once, one layer of silence stacked upon another.

I got a taste of this myself when my husband called me in early 2016: “They’ve rejected my application for a Letter of Consent.” As a foreigner, he would not be allowed to work in Singapore without it. He would have no choice but to seek employment — and thus residence — elsewhere.

The

Ministry of Manpower websitehad told us it would take seven working days, but followed it up with the catch-all contingency of “some cases will take more time”. An earlier application for an employment pass had already been rejected. We put our hope in this Letter of Consent — a scheme extended to the foreign spouses of Singaporean citizens who have already secured offers of employment. We waited for a week, then another and another. There was no indication why it was taking so long. It took two months for us to learn the result.

It made no sense. He was young and highly-qualified and had already been offered a position in a large, well-established multinational company. The stipulated salary was well above the threshold specified for a work visa, and as a spouse of a citizen he didn’t count towards the employer’s quota for hiring foreigners.

No explanation was forthcoming. “We would like to reiterate that each work pass is assessed on its own merit in consultation with the relevant government agencies. We are unable to disclose details of the rejection,” read the boilerplate email. Further prompting only resulted in another terse response: “Our position on this [Letter of Consent] application has not changed. We regret that we are unable to assist any further in your enquiries.”

One night at a cocktail reception, I told an acquaintance — an artist with whom I shared many mutual friends — about our situation. I tried not to make allegations; I didn’t want to sound melodramatic. “We can’t figure out what the problem is,” I said. “They haven’t told us the reason. I don’t know why they’re doing this.”

He didn’t hesitate. He looked me straight in the eye and said, “I think we all know

why.”

He was referring to my work as an independent journalist, my commentary on a range of social and political issues, my advocacy for the abolition of capital punishment and other causes. In that shared look, we both thought of the stories we’d heard many times before.

I was studying in Wales in 2013 when I heard that an academic I knew — a well-known commentator on Singapore’s media and political landscape — had lost his position in a local university after being

denied tenure for the second time. My professor had been one of his case reviewers and

insisted he’d been more than qualified. Other dazzling testimonies came in, from colleagues and students alike, but to no avail. There was never any clear, official reason for this decision, even though he was told that it

wasn’t because of the quality of his teaching.

At the time, I was shocked and outraged that a respected educator could lose his job without justification or accountability. I’ve since learnt that he was only one of many; stories of educators/researchers/journalists being denied work visas or tenure or clearance are now so familiar to me they are almost trite.

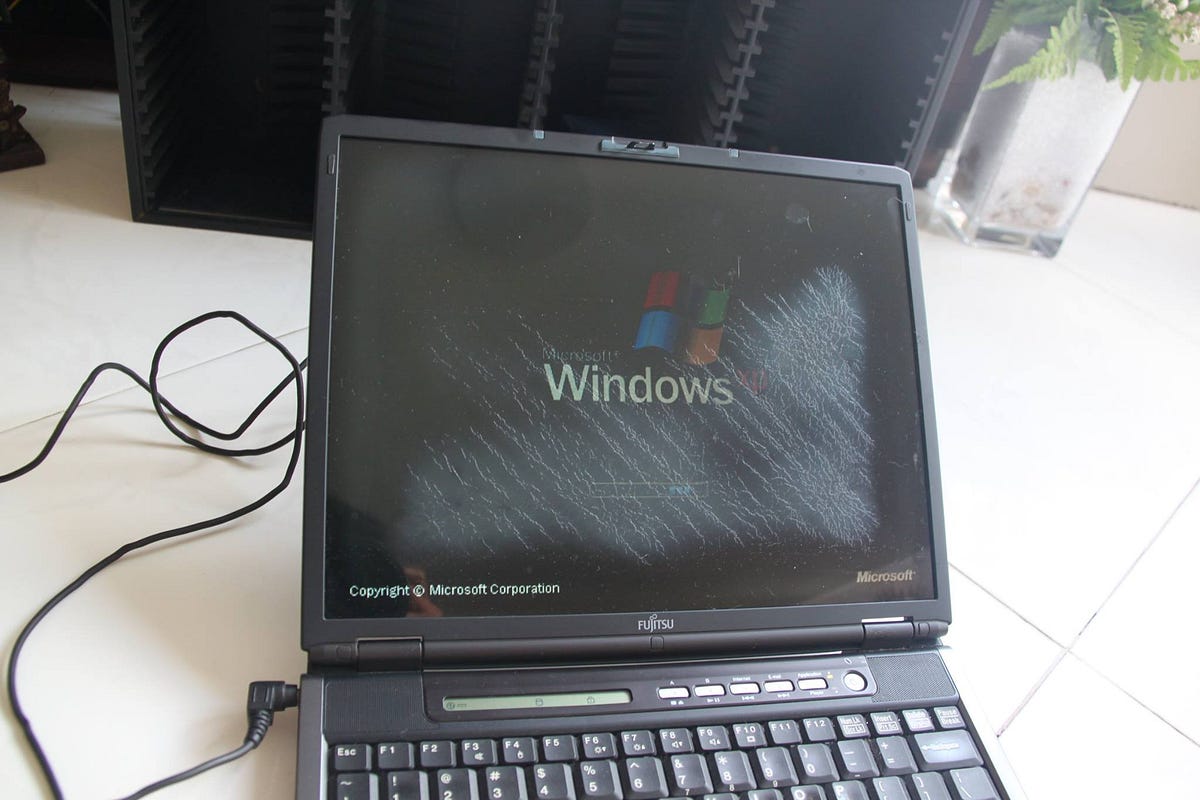

Teo Soh Lung’s electronic devices were returned to her in July 2017, over a year after the police had seized them. The laptop was damaged. (Photo: Teo Soh Lung)

Then there are the investigations. A month after the 2016 by-election in a small constituency the Elections Department announced that they’d made police reports against two activists. They accused the two of breaching election advertising rules by posting on their personal Facebook pages the day before the vote. The police questioned both for hours, then raided their homes. Their electronic devices — mobile phones, laptops, hard drives — were seized. The offence was “arrestable”; no warrant was necessary.

The police came knocking on my door at the end of a long weekend in September. They handed me a letter informing me of an investigation into an illegal assembly: a vigil for a death row inmate’s imminent execution. A vigil at which police officers had been present, and had allowed us to stay. We would later find out that our names had been flagged with the immigration authorities, and that we were not allowed to leave the country before our interrogations.

These are the stories you hear again and again when you fall in with Singapore’s activists. They’re passed from one to another, mentioned at events and in WhatsApp chat groups. Sometimes you hear about it as it’s happening; a friend mentioning in anxious tones that his or her tenure application has been pending for too long. Sometimes you hear about it just in time to drop everything and rush to a police station to wait for your friends. Sometimes you only hear about it later, and realise you’ve missed the chance to say goodbye to someone who’s given up and moved away.

“Never ascribe to malice that which is adequately explained by incompetence.” It’s an oft-quoted saying, but most people forget the second half: “…but don’t rule out malice.”

It’s hardly helpful when locked in such a conundrum. Is it, or isn’t it, malice? How do we prove it either way? Is it possible to identify oppression from its silhouette alone?

This is the autocrat’s dream: a state of affairs that privileges the powerful, a way to exert control without attracting public shame. When there is no evidence or clear sign of oppression, there is no report or complaint to make, no documentation to file for posterity. When a survey from a human rights organisation asks you if activists face reprisals from the state for their work, “not really, but…” isn’t something you can place on a Likert scale.

The effect is psychological, too. After a while, you don’t know what to believe anymore. Is the state really so insidious, so manipulative, or are you being a conspiracy theorist? You begin to question all that’s happened, to doubt yourself. You start asking, “Am I sure, really

sure, this is what’s going on here?” and know that you’re beating yourself up with questions you can never answer. It gets to the point where you’ve second-guessed yourself so many times you no longer know what to say.

It’s disempowering at a very fundamental level. When you don’t know if, what or when “things” can happen, it becomes much easier to withdraw, to mind your own business and keep your eyes cast down. Look after your little corner of the world, steer clear of anything that might be contentious. Stay afraid.

I’ve seen this in conversations with Singaporeans, family members included. I talk to them about all the problems I’ve seen and the issues I’ve covered as an activist and a journalist. They nod their heads or tut in sympathy, then say, “Yah, it’s very bad. But what to do? At the end of the day, you have to keep your job and feed your family.”

What to do?

Unpacking this aspect of life in Singapore, and realising how it’s always been a part of my own consciousness, has been a journey of discovery, shock, fear and anger. Today, my husband and I continue to muddle through, renewing visit passes six months’ at a time. We’ve had to live in separate countries for a while, and might have to do so again. We still don’t know why it’s like this. When I finally wrote about our experience, almost a year after we realised he could not work in Singapore, I framed my

blog post in terms of the challenges transnational couples face. At that moment, I dared not assert more.

These are things that can’t be written about within the boundaries of conventional journalism, but this

is Singapore: a country of citizens living in comfort and relative luxury, yet cautious and afraid of a shadow they can’t quite name. A country of people as privileged as they are disempowered.

Party flags and onlookers at an opposition party rally during the 2011 elections.

I saw this fear during the 2011 general election, when an ice cream vendor yelled at me for photographing him outside a packed opposition rally. He had festooned his little cart with party paraphernalia — flags, umbrellas, pins — to attract rally-goers, but having his photo taken made him nervous and afraid. “You don’t know what ‘they’ will do,” he said.

Who are “they”, and what

will“they” do? What

can “they” do? What

won’t “they” do? These were not questions the ice cream uncle could answer. They are not questions any of us can answer. They create an environment where the danger feels omnipresent but vague; an environment that encourages not action or resistance, but paralysis.

And that, of course, is the point.

A single golf clap? Or a long standing ovation?

By clapping more or less, you can signal to us which stories really stand out.

Kirsten Han

I'm a Singaporean freelance journalist and writer. I'm happiest writing about social justice and human rights issues, wherever they may be in the world.

More from The Spuddings Blog

Everyone feels the chill when the wind blows in Singapore

Kirsten Han

Kirsten Han

Related reads

Chatbot Experiment: Warby Parker Bot

Ted Wu

Ted Wu

More on Politics from The Spuddings Blog

30 years on, it’s time for the truth about Operation Spectrum

Kirsten Han

Kirsten Han

Responses

Conversation with

Kirsten Han.

Chungkwong Yuen

Oct 23

Chungkwong Yuen

Oct 23

have you heard of Nicole Seah? the 2011 election? do they fit your picture of SG?

maybe you should interview Nicole Seah, Kevlyn Lim and He Ting Ru, to discover why 2011 was different and how things went back afterwards

1 response

Kirsten Han

Oct 23

Kirsten Han

Oct 23

Yes, of course I have heard of Nicole Seah and the 2011 election—in my piece there is also a brief mention of me covering the 2011 election.

2011 was a very interesting election that gave many people the impression that we were heading towards a “new normal” of more openness and increased opposition presence in Parliament…