Turns out there was at least 1 case in Singapore that was reported.

https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/deadly-insomnia

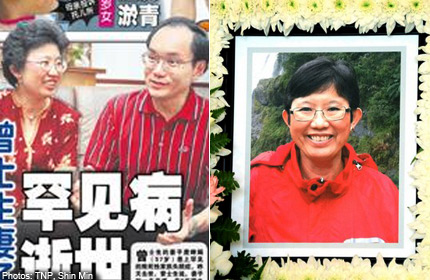

The sleep disturbances began shortly after Mrs Patricia Chan's 57th birthday in April this year.

Her husband, former minister of state Chan Soo Sen, recalled: "She would talk in her dreams, gesticulate, roll around and kick."

As the weeks passed, the symptoms got worse.

"She would suddenly fall asleep while talking or being driven in the car," said Mr Chan, who is also 57.

The talking in her sleep got louder, and the gestures more pronounced.

But if she felt tired or drained, she did not show it. She kept up her routine and was active and cheerful.

This was a day she had long been prepared for, Mr Chan told Mind Your Body last week.

Eight years ago, Mrs Chan learnt she carried the gene for an extremely rare and traumatic disease - fatal familial insomnia - which is said to affect only about 100 people in some 40 families worldwide.

Sufferers live with progressively worsening insomnia and brain function as the brain deteriorates.

Mrs Chan had herself tested when her elder brother died and his doctor suspected the cause was fatal familial insomnia.

Her mother also suffered from similar symptoms before she died in 1976. Mrs Chan then knew she had a 50 per cent chance of inheriting the gene and disease.

Her blood sample had to be sent to a laboratory in Europe as the test was not available here.

Not one to bemoan her bad luck, however, she did not let the diagnosis affect her life, said her husband. She continued to be active in church, meet her friends and care for church members who were sick.

"It doesn't help if you get emotional about it. We accepted what would be happening and decided that, meanwhile, we would continue to live normally for as long as we could," he said.

This cheerful personality and love for her family was what drew him to her in the first place.

She came from a small town in Malaysia. They met in 1977 at Oxford University in Britain, where she was a student nurse and he was studying mathematics as a President's Scholar. They were married in Singapore in 1981. When they had their two boys, Mrs Chan gave up her career as a paediatric nurse to take care of them. Mr Chan retired from politics in 2011 and now works part-time as a business adviser.

When she fell ill, Mr Chan said, there was just one thing she feared - losing her memory.

He said: "I told her: 'Don't worry. Even if you forget about all of us, all of us will remember you forever'."

DISEASE SETS IN

While they could, the couple did things together. They visited their younger son Richard, 24, a dentistry undergraduate in Australia, at the end of June. They have an elder son Nicholas, 28, who is a civil servant.

"In July, after we came back, her short-term memory began to deteriorate progressively. She started to forget where she put her keys and her mobile phone. Then, she couldn't remember what she had just eaten, who she was with and what happened yesterday."

She also began to mix up day and night. "Her sleep became irregular. She would wake up in the morning, but would think it was night."

While many facets of fatal familial insomnia remain unknown, it is clear that sleep is important for brain health, said Professor Einar Wilder-Smith, a senior consultant at the division of neurology at the National University Hospital.

"If we are forced to keep awake beyond 72 hours, we become psychotic, start to hallucinate and the brain starts to malfunction," he said.

Fatal familial insomnia is caused by a genetic mutation in a prion protein. It is one of several such rare, progressive and neurodegenerative disorders that include Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, where dementia sets in after a few months.

Fatal familial insomnia sufferers are initially aware of what is happening. There is no cure or treatment for fatal familial insomnia, which typically strikes in middle age. Most people die within 18 months.

Sufferers of this disease cannot get past the first stage of sleep, said

Prof Wilder-Smith. That is the lightest sleep stage, where if the sleeper is awakened, he may feel he has not received any rest.

As the brain degenerates, a person first loses the ability to do tasks that require manual dexterity or complexity, such as abstract thinking and speaking, said Prof Wilder-Smith.

Simpler tasks, such as lifting the hand or closing the eyes, go later.

"Breathing is a less complex task, so that function is lost at a later stage," he said.

By August, Mrs Chan had lost control of her fingers and her feet, and had to use a wheelchair.

"When she sent SMS messages, she would type nonsense and send it to various people," said Mr Chan.

"She was unable to write or use chopsticks. We got her to use a spoon but later on, she was unable to find her mouth with the spoon."

She became unstable and prone to falls. In the night, if she needed to use the bathroom, she would not wake her husband.

"A few times, I found her in the toilet, with her head just a few inches away from the steps. We installed a grab bar but she could not grab it. She could not be left safely on her own," said Mr Chan.

"Seeing her sick like that was really very sad as she was a very cheerful and energetic person."

COMFORT AT HOME

She was hospitalised in August, but the only option available to her was palliative care. As he had "no heart" to admit her to a hospice, he opted to have her at home, cared for by two full-time nurses.

While her condition worsened, he set himself three objectives: to keep her safe, comfortable and happy.

So, though it was a very sad time, there was also happiness.

He and Nicholas took care of her on Sundays. He also scheduled a one-hour gap between the day and night nurse in the morning as well as a two-hour gap in the evening so he could spend some time with her alone each day.

He would wheel her out for walks and dinner. Sometimes, they would go on the bus or the MRT.

"I noticed she was very happy. She sat up straight and pointed here and pointed there. She spoke but I didn't know what she was saying. By then, her speech had become very slurred," said Mr Chan. "But if she was happy, I was happy too."

By September, Mrs Chan had started to mix up past and present.

"She would talk about our younger son having to go for music lessons: 'It's 7.30am. How come he hasn't gone to school?'

"'He's in Australia', I would tell her. Fifteen minutes later, she would say: 'It's 7.45am. How come he hasn't come down?'," said Mr Chan.

"Sometimes, I would ask her: 'Do you know who I am?' "

She would give him a mischievous smile, he said.

"She knew that she had a bad memory and was trying to be playful about it."

He learnt that caregiving is a tremendous responsibility that should not be shouldered alone.

"If you cannot cope, it ends up undermining your love for the person you are caring for. It's far better to say: 'Yes, I need help.' Mobilise friends, family and consider institutional care. If you are overwhelmed, you're not going to be any good."

Mr Chan said he was grateful that his wife had many good friends who came to the house constantly to keep her company.

"There was never a dull moment. They were there to make her happy. They bought her lunch and snacks. I never had to worry about her lunch," he said.

"In sickness, your greatest enemy is loneliness. She was happy because she was not lonely. She still wanted to talk, even though her speech (function) went progressively, and her friends were willing to listen. We didn't understand her, but we believed that if she kept on talking, she must be happy."

PEACEFUL END

Nonetheless, towards the end, it became tough on everyone.

"We could sense the next stage was coming. She began to lose bowel control. She started to wet the bed and defecate in bed. She also started to show difficulty in swallowing," he said.

And she would not sleep at all. Instead, she would hallucinate.

Still, he made plans to accompany her on a trip to Krabi in Thailand with her friends.

One day before the trip, however, on Oct 27, Mrs Chan suffered cardiac arrest. The hospital put her on life support, but declared her brain dead 72 hours later.

Mr Chan consulted his sons and they decided to take her off the ventilator.

"The next morning, we called in the pastor. Her closest friend was there. Together, the five of us stayed with her till the reading on the machine went flat," said Mr Chan.

The end was peaceful but premature, he said.

"We expected her to live about 18months, but she lasted seven to eight months."

In the last stage of fatal familial insomnia, total dementia sets in and the patient slips into a coma due to the brain degeneration.

Said Prof Wilder-Smith: "Ultimately, the patient stops breathing. But it takes a long time for the brain to degenerate to a stage where respiratory functions stop."

More often than not, somebody with severe brain degeneration will die from a secondary cause, such as an infection or thrombosis, he said.

In Mrs Chan's case, her heart stopped.

Mr Chan said he, his wife and their sons were able to face the disease so calmly because they had faced up to the truth, as difficult as it was.

"Somehow, we rationally accepted it as it had happened to her mother and her sibling," he said.

"The moment you ask 'why me' and wallow in self-pity and get angry with everybody, you are going to fail in your objectives and the outcome is still the same."

When asked whether his sons have been tested, he said: "I leave the decision to them. One of them has tested negative."

https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/deadly-insomnia