‘We’re at the brink’: Kidney disease crisis looms in Singapore as some doctors urge more action

Many patients discover their condition only when they suffer kidney failure. With six people in Singapore diagnosed daily, the NKF warns of a lack of dialysis spots for new patients, while some doctors make a case for early kidney-function screening..jpg?itok=uKdP7xro)

Nearly every spot in the National Kidney Foundation’s biggest dialysis facility, the Integrated Renal Centre, is filled.

• More than 300,000 people have chronic kidney disease, but another 200,000 could be going undetected.

• There may not be enough dialysis spots for new patients if nothing changes, says the NKF.

• Health screening is a solution, but some doctors call for more broad-based coverage, including in the Screen For Life programme.

• Early-stage detection means a better quality of life and more manageable costs.

Christy Yip

@ChristyYipCNA

Eileen Chew

22 Jul 2023 06:00AM(Updated: 18 Aug 2023 05:37PM)Bookmark

WhatsAppTelegramFacebookTwitterEmailLinkedIn

In partnership with the National Kidney Foundation

SINGAPORE: Every day at 11am, Singapore’s biggest integrated renal centre is abuzz as if, as Shanthini Durga put it, “World War Three” has struck.

ADVERTISEMENT

The staff nurse and her team darted about from patient to patient to help them get off their dialysis machines. Outside, the next batch of 40 patients had started queueing for their turn to be strapped in.

As she deftly pulled needles from veins and disinfected tool after tool, Shanthini said: “That’s how fast we need to move.”

The need is to make sure the day runs like clockwork, with three dialysis cycles every day.

It did not use to be this hectic, however. Four years ago, when Shanthini started the job, the centre was “only half full”. Today, nearly every slot in the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) dialysis facility is filled.

Indeed, across its 41 centres, the NKF receives about 100 new applications for a dialysis spot every month, nearly double the figure from five years ago, said its medical director, Jason Choo.

ADVERTISEMENT

Yet, the 9,000 or so patients in Singapore who have kidney failure are merely the tip of the iceberg — there are more than 300,000 people with chronic kidney disease (CKD), the insidious precursor to kidney failure.

Those are only the detected cases: For every 10 diagnoses, it is estimated that five to seven people do not know they have the condition, said Yeo See Cheng, the head of renal medicine at Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH).

This means 200,000 more people could be walking around unaware that their kidneys are suffering. If left unmanaged, CKD will progress to kidney failure.

WATCH: Inside Singapore’s fight against kidney failure — A looming dialysis crisis? (20:33)

The implication is that “in the next couple of years”, if nothing changes, dialysis centres will have no spots for new patients, said Choo.

ADVERTISEMENT

“We’re at the brink … in terms of patient numbers,” he added. “At the rate things are going, we’ll need to have dialysis centres at every HDB block.”

A SILENT KILLER

About a third of the patients Yeo has seen had no idea their kidneys were in bad shape until too late. They usually “crash-land” in TTSH’s accident and emergency department, either with legs too swollen to bear or an insatiable belly itch.By that time, the patient’s kidneys are usually on the brink of failure, the damage irreversible. Patients would have to quickly start on dialysis, which will be a lifelong therapy unless a transplant is on the horizon.

“It’s like a silent killer,” said Yeo. “Because in the early stages (of CKD), patients don’t have any symptoms. They feel normal, they feel healthy, even though their kidney function has declined.

“Many patients don’t even realise until they’re at stage five, known as kidney failure.”

ADVERTISEMENT

That is when almost 85 per cent of the kidney has already deteriorated. “It’s a pity,” he said. “We always imagine how life could’ve been very different for this group of patients if they’d been identified earlier.”

For one thing, their lives would not revolve around being strapped to a machine thrice weekly.

“I’ve been walking the same road for nine years,” said Radheana Zamri, who was 21 years old when she learnt that she had kidney failure and, at 30 now, is the youngest patient at her centre.

On dialysis days, she is out of doors by 6.50am, ready with a snack bag to get through four dreary hours of therapy.

She had been living with Type 1 diabetes, an autoimmune condition where the body is unable to regulate blood sugar, since she was eight years old but thought she would possibly develop CKD only later in life.

Why CKD is so insidious

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is caused by conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and inflammation or genetic factors. They can cause kidney cells to die, and these cells do not regenerate.Despite the damage, the kidney continues to perform its function: to remove toxins and excess fluid from the body.

On the outside, patients may feel normal for many years before CKD progresses to a stage where more and more cells die, said senior consultant Tan Chieh Suai, the head of Singapore General Hospital’s renal medicine department.

As the kidney weakens over time, toxins become harder to filter out and will accumulate in the body. Only then do overt symptoms appear. By that time, it may be stage five of CKD.

Expand

Diabetes, both Type 1 and Type 2, is the commonest cause of CKD in Singapore. Other causes include hypertension, inflammation and genetic factors.

Kidney failure patients like Radheana can only drink between 500 millilitres and a litre of water a day and have a long list of foods to avoid, as the kidneys can no longer filter out toxins and excess fluid nor regulate blood pressure efficiently.

A quick scan of their dietary requirements shows that patients must avoid high-phosphate foods, which include processed foods (instant noodles, potato crisps, et cetera), dairy products (milk, yoghurt and cheese, etc) and dried products (seaweed, fish/prawn crackers, anchovies, etc).

Patients should also avoid high-potassium foods, which include wholegrains, nuts, seeds, coconut and related products and herbal medicine drinks, as well as reduce their salt intake.

But what is especially difficult for Radheana is the loss of freedom.

“One thing: travelling,” she cited. “(As) young people, we like to travel. My family also always like to travel, so sometimes I can’t follow them. Or when they want to stay longer, I can only go for a shorter (time).”

Even finding time to meet friends has been tough, especially on dialysis days. “It’s like my life is here (at the centre). This is my lifeline. If I (don’t) go, then that’s it,” she said.

It is “very devastating” when patients end up with kidney failure, said NKF head of nursing services Pauline Tan, who has spent more than 30 years of her career journeying with such patients.

“Many of them are in denial. … They go into an angry, angry stage: ‘Why is this happening to me?’” she said. “It causes a lot of burden not just to yourself but also … a lot of burnout for the caregiver.”

According to the Singapore Renal Registry’s 2021 report, six new patients are diagnosed with kidney failure every day.

Related story:

NKF urges people to go for kidney screening amid rising number of renal failure cases

And dialysis costs in Singapore in 2021 were estimated to be about S$300 million, stated an article last year in the Annals, the journal of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore.“The cost is going to rise exponentially … if we don’t do anything to stem this flow of patients,” said NKF’s Choo.

By 2035, almost a quarter of Singaporean residents aged 21 and above could have CKD, of which more than half — about 500,000 cases — will be undiagnosed, forecast a 2018 study published in the International Journal of Nephrology.

And what is still needed are the people who run the dialysis centres: nurses. “I’m training new renal nurses like nobody’s business. Non-stop,” said Pauline Tan.

The situation is compounded by the exodus of nurses to other countries during the pandemic.

“It takes six months for a nurse to be competent to manage the dialysis machine, manage the patient,” she said. “I lost a lot of nurses … who were very well-trained already. And I’ve got to start all over again.”

She summed up the NKF’s foremost concern beyond costs: “If we don’t have enough dialysis units, if we don’t have enough nurses, what’s going to happen to the patient?”

THE DIFFERENCE SCREENING MAKES

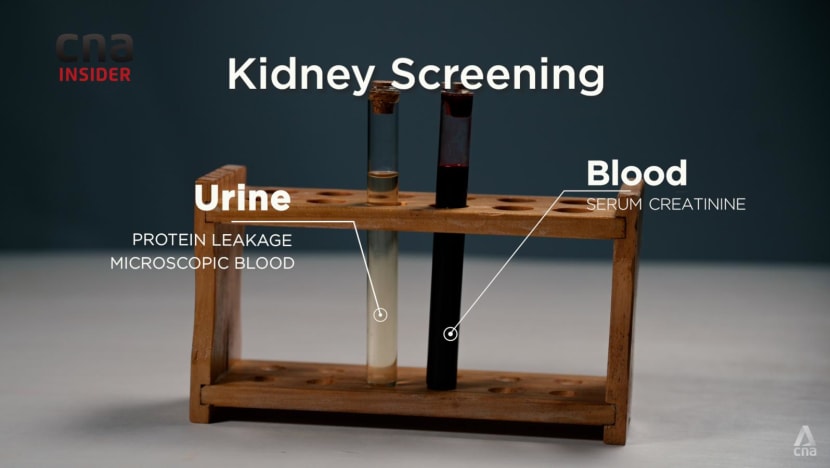

The “only way” to catch the silent killer, said Singapore General Hospital (SGH) senior consultant Tan Chieh Suai, is through screening, which involves blood tests and urine tests.“Most of the time, the routine screening people are aware of is … for cholesterol, for diabetes,” said Tan, SGH’s head of renal medicine. “But having a normal blood sugar level or normal cholesterol level doesn’t mean the kidney is healthy.”

A urine test can check for microscopic traces of blood or protein, which would indicate that the kidneys’ filtering function has been affected, he said. A blood test for the presence of creatinine, an indicator of toxin in the body, would also tell if the kidneys are performing well.

It was these tests that made all the difference to Fuad Aliman. He was referred to a kidney specialist when he was 37 years old, after he sought treatment at a polyclinic for gout related to his diabetes.

Sixteen years on, he counts himself “very fortunate”: His test results showed a leakage of protein in his urine, which indicated early-stage CKD.

He has since had to only rely on oral medication to maintain his kidney health. He also shed 70 kilogrammes — half his weight — over the years by exercising, even running marathons and climbing mountains, which has helped to reduce stress on his kidneys, said Tan, his doctor.

Above all, said Fuad, “I didn’t have to go through the hardship of dialysis”.

Who should go for kidney screening

With possibly more than 200,000 people going about their business without knowing that they might have CKD — owing to its silent symptoms — it is vital that individuals get their kidneys screened.Kidney screening involves a simple blood and urine test and is key to detecting CKD. Talk to your family doctor for more information.

If your workplace offers basic health screening, then opt for packages that include a kidney function test, which can cost around S$50, depending on the provider.

For individuals at higher risk of developing CKD, an annual kidney screening is particularly essential. The risk factors include:

• Pre-existing medical conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, obesity and/or heart disease.

• A family history of kidney disease, diabetes and/or hypertension.

The National Kidney Foundation runs a CKD intervention clinic, which provides free kidney screening for the at-risk and high-risk groups. For more information, visit: https://nkfs.org/kidney-failure/ckd-clinic-overview/

Expand

If started in the early stages of CKD, drug treatments can help to reinforce the kidneys, said Thomas M Coffman, dean of Duke-NUS Medical School and chairman of the NKF’s medical advisory committee.

Clinical trials have shown that medication helps to delay the disease’s progression and, ultimately, the need for dialysis by an average of three to four years — and in some individual cases by 10 years or more, cited the professor.

“That’s why it’s important to identify the people who need to be on these drugs, and make sure that they’re taking them,” said Coffman, who is also a nephrologist. “You’d be buying yourself the opportunity to maintain a normal life.”

The cost savings are also substantial, he added. Medication can cost around S$50 a month, whereas haemodialysis usually starts at S$2,500 per month. Peritoneal dialysis — a home-based, self-administered, needle-free treatment — can cost between S$1,300 and S$2,000.

“(Dialysis) never takes a day off. You’d be saving yourself and your family from a substantial financial burden (and) poor quality of life,” said Coffman.

Although patients such as Fuad still carry a “lifetime risk” of kidney failure, said Tan, he tells them that “every year that you aren’t on dialysis, you’re a winner”.

Previous

Next

- 1

- 2

THE NEED TO OVERCOME INERTIA

Life could have turned out very differently, however, for Fuad. He almost passed up the referral to the kidney specialist all those years ago.“I thought, ‘Why do you want to go through all this hassle? Just get painkillers, relieve (the gout), then you can go back to work,’” he recalled.

These days, he is taking no chances. He has renal tests done every six months, and his kidney health has remained stable.

Family physician Elly Sabrina Ismail is all too aware of human inertia when it comes to health screening — and of the heartache when people find out about their kidney disease too late.

“A lot of people have this mindset: I don’t want to know the outcome (because) my whole life (may have) to change,” said the 53-year-old, who runs Banyan Clinic in Woodlands.

Additionally, when patients do not feel sick, health screening is far from their minds, she added. This is how CKD is insidious.

Also, some patients who already have chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension may be in “denial”. When first diagnosed, “a lot” of them do not necessarily want to receive treatment and further tests right away.

“(They’d say), ‘Let me think; give me one month, then check again whether my blood sugar level is better,’” cited Elly. But usually, by the time doctors pick up signs of diabetes, the patients might have already had it for a couple of years, she said.

It is “very disheartening” to her that follow-ups can be patchy, especially when a patient returns later, already diagnosed with kidney failure. “It could at least have been delayed,” she said.

“It’s very sad because I managed to detect (signs), but I didn’t manage to keep him or her on follow-up, to keep him or her motivated to continue the journey (to get) healthier.

“I also feel guilty that I was unable to make that change.”

‘JUST LIKE INSURANCE’

One thing that has helped to get more people to check for hidden diseases is the national Screen For Life programme. It offers eligible citizens and permanent residents subsidised screenings based on their age and gender.Basic health screening, even pap smears to check for cervical cancer, can cost S$5 or less.

Elly’s clinic offers health screening, including as part of Screen For Life. But while the initiative has reduced the cost, what is “frustrating” for her is that kidney function tests — which go beyond testing for diabetes — are not included.

“It’s (already) so difficult to get somebody to come for health screening. So when you catch them, you (must) make full use of the opportunity,” she said.

Currently, annual screening for kidney disease is recommended for patients with risk factors, such as diabetes, hypertension, obesity or a family history of kidney disease.The extra tests that we do to screen for the kidney function aren’t very much, as compared to the mountain of cost that we’re going to have if the patient ends up with kidney failure and needing a dialysis machine.”

“But if I had it my way, I’d do broad screening across the population of adults in Singapore,” said Coffman, who believes this would mean fewer people needing to “see a nephrologist or to get their kidney failure treatment”.

“I know what happens when you get kidney disease. I know what the impact is.”

And while screening can be a scary prospect, Elly would have people know that “80 per cent of the time, it’ll turn out all right”.

“That gives you the freedom to carry on with your life. But if you detect a problem, at least you’ll know what to do,” she said. “It’s just like insurance.”

A MISSING LINK?

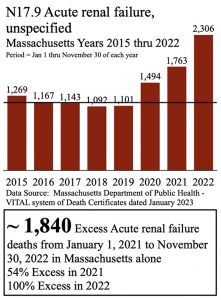

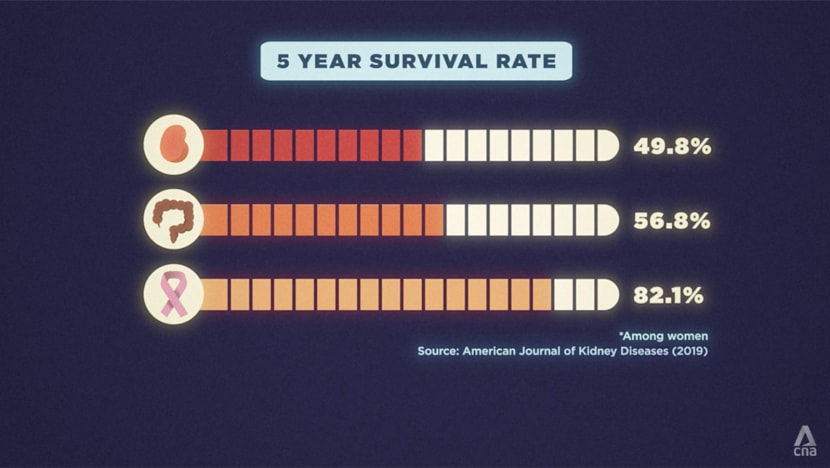

Awareness of kidney disease, however, is lacking, doctors and nurses agreed. “For a long time, we’ve been clued-in on things like cancer,” said NKF’s Choo. “But kidney disease is just as bad.”The life expectancy of those with kidney failure is also as bad or even worse than some better-known cancers, said Coffman.

In a study in the American Journal of Kidney Diseases, the five-year survival rate for patients with kidney failure was 51 per cent, worse than that for colorectal and breast cancer patients (56 and 82 per cent respectively).

And while Singapore’s top causes of deaths, like cancer and heart disease, get a lot of awareness, said Tan from SGH, patients with kidney disease are themselves at high risk of heart disease. Many of them die from comorbid heart disease than from kidney failure itself.

For Shanthini, it is sobering to see the volume of patients needing care at the NKF Integrated Renal Centre. “(If) one patient passes away, within two to three days, … a new patient’s coming (to fill the spot),” she said.

“We don’t want to see more patients”.

Doctors Yeo and Tan feel the same way. Even if it would mean being out of work, “that’ll be a very happy problem”, said Yeo.

“If we’re so successful in helping our patients to detect CKD and to prevent kidney failure, I think that’ll truly be one of the joys of my career.”