In the early 1980s, New Zealand was on the brink of economic collapse. Two oil price shocks had saddled the country with high inflation, and the UK’s decision to join the European Economic Community a decade earlier had cut off access to a key export market. Successive governments had compounded the pain with a series of policy errors — throwing around subsidies, awarding inflationary pay deals and trying to control prices, while keeping interest rates too low and taxes too high. The result was soaring unemployment and mounting debts. No wonder some dubbed New Zealand the Albania of the South Pacific.

Yet over the remainder of that decade, New Zealand was transformed into one of the most prosperous countries in the world. A new Labour government took office in 1984 and embarked on a form of shock therapy that came to be known as “

Rogernomics,” after Finance Minister Roger Douglas. The government removed exchange controls, slashed subsidies, privatized services and handed responsibility for setting interest rates to a newly independent central bank. New Zealand also introduced a different accounting approach throughout the public administration.

It is impossible to separate out the precise impact of each of these policies. But

Ian Ball, a former senior Treasury official, professor of public finance management at Victoria University in Wellington, and one of the authors of

Public Net Worth (Palgrave Macmillan, February 2024), says accounting reform was among the most consequential.

Accounting is notoriously dry stuff. But switching to an accruals-based approach used in the private sector, and away from the cash-based systems traditionally used by governments, forced departments to think long-term and maximize the efficient use of assets. This is especially relevant in the UK at the moment with the government on the cusp of

major budget reform.

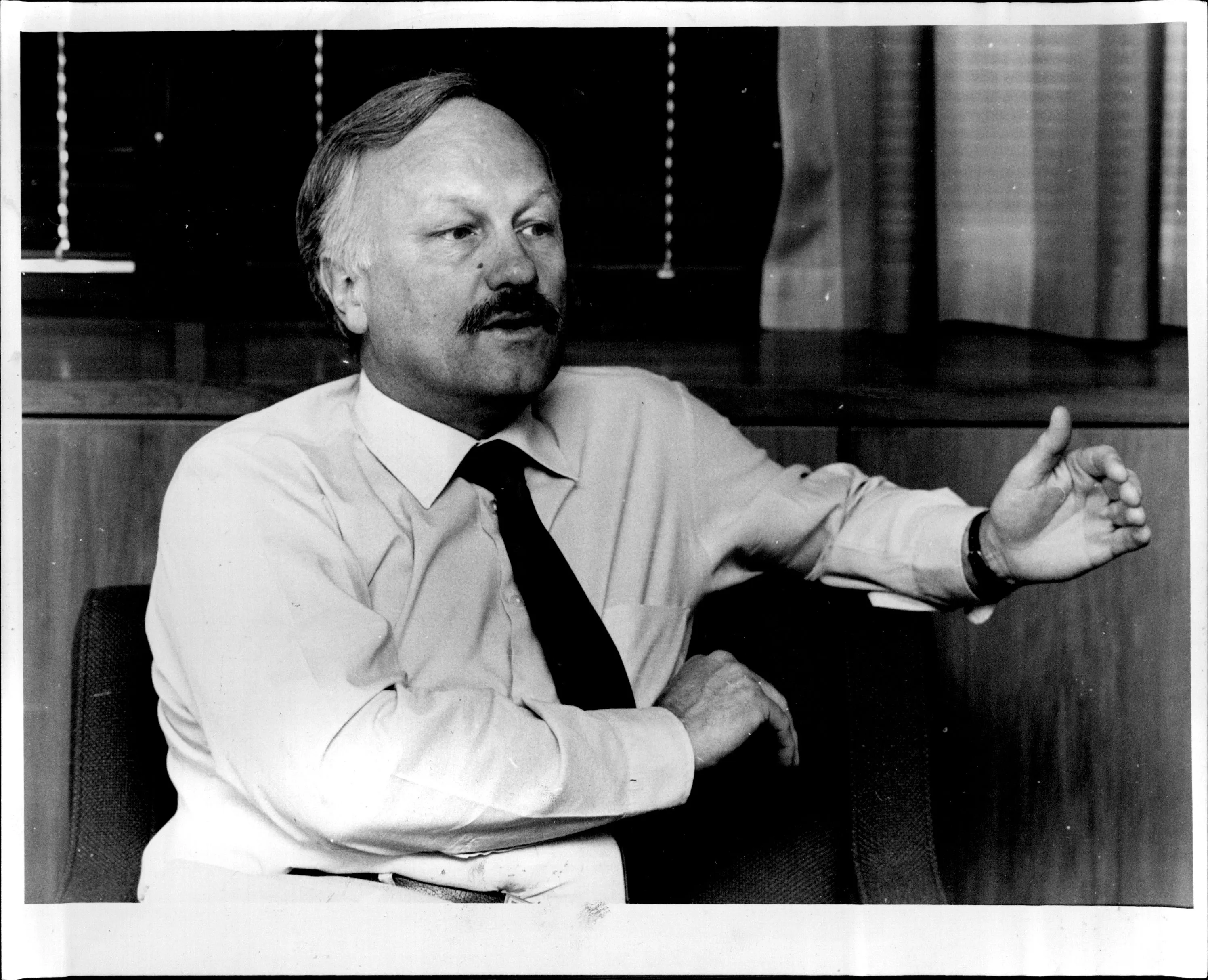

New Zealand Finance Minister Roger Douglas in 1985.Source: Fairfax Media Archives/Getty Images

To see what this means in practice, take the case of public sector pensions.

Under a cash-based system, the debt is accounted for when the pension is paid, which could be years in the future. The government has little incentive to make any provision for it.

But with accrual-based accounting, the cost of the pension commitment must be recorded as a liability when the benefit is earned. That led the New Zealand government in 2001 to establish a Superannuation Fund to pay for future pensions. Today, this quasi-sovereign wealth fund

is regarded jealously by countries that wish they had something similar.