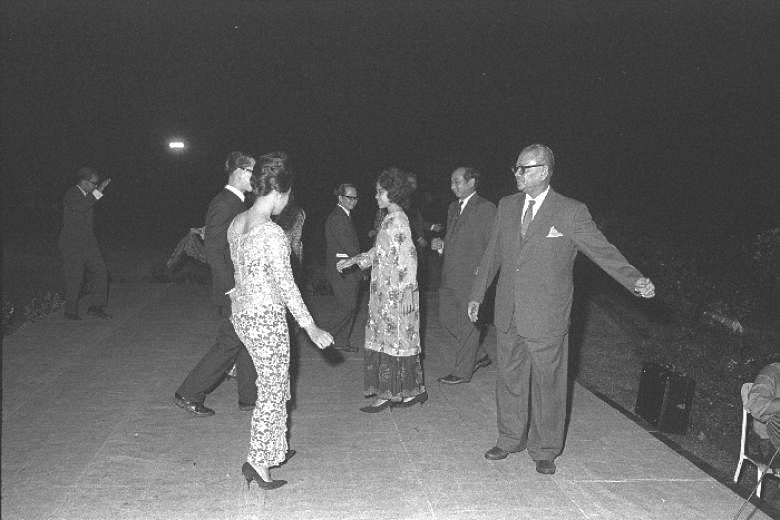

Malaysian Prime Minister Tengku Abdul Rahman (right) and Minister for Finance Dr Goh Keng Swee (second from right) dancing the joget during opening of Rumah Temasek at Kuala Lumpur in November 1963.

PUBLISHED 14 MAY 2016, 5:00 AM SGT

When Singapore separated from Malaysia in August 1965, it continued to use a common currency with Malaysia and Brunei, the Malayan dollar. Issued by the Board of Commissioners of Currency of Malaya and British Borneo, the Malayan dollar was a currency that generations on both sides of the Causeway were accustomed to.

Despite their strained relations, the two governments agreed to discuss how the common currency arrangement could be preserved.

Singapore's Finance Minister Lim Kim San, as early as October 1965, just two months after Separation, had raised the matter of a common currency with his Malaysian counterpart Tan Siew Sin.

Mr Tan authorised the Governor of Bank Negara, Tun Ismail bin Mohd Ali, to initiate discussions with Singapore. Bank Negara's suggestion was to continue the common currency arrangement, but with it issuing currency for both countries. There could be differences in design to differentiate the currency issued in Malaysia from the one issued in Singapore, though either one would be legal tender in the other.

The other issue that Singapore raised concerned the control and ownership of the reserves, in the first instance, the pool of reserves transferred from the existing currency board.

This, more than the type of monetary system, was a fundamental issue for Singapore: it would only agree to negotiations if there were binding assurances that its reserves would remain under its control and management. Bank Negara understood Singapore's concern and agreed to modify its original proposals concerning the arrangements for the management of reserves.

Dr Goh was then Defence Minister but was influential in shaping the government's strategy in the currency talks. He took it on himself to compose detailed memoranda to explain to his Cabinet colleagues the complexities of monetary policy, the implications of the proposals being tabled and the stand Singapore should take.

Far from viewing Dr Goh's interventions as intrusions on his turf, Mr Lim welcomed them. Old friends from their days at Raffles College - Mr Lim had been best man at Dr Goh's wedding - they formed a formidable team: Dr Goh the economic theoretician and practitioner par excellence, and Mr Lim the businessman-turned-politician, a "political entrepreneur…who seized opportunities using powers of analysis, imagination, a sense of reality and character", as Mr Lee was to describe him later

Significantly, Dr Goh seems to have been the most sceptical among his senior colleagues about the arrangements for the common currency.

Dr Goh felt Singapore should seek two safeguards: First, each government's reserves should unambiguously be under its own direction. And second, Bank Negara should operate only as an agent of the Singapore government, completely subject to the direction of the Singapore Finance Minister in matters affecting Singapore.

He forecast that these safeguards, though absolutely necessary for Singapore, would be unacceptable to Kuala Lumpur. Singapore should therefore be prepared for a breakdown in the negotiations, he advised.

Still, notwithstanding Dr Goh's reservations, and somewhat to his surprise, the talks progressed to the point of producing a Final Draft Agreement. It provided for a common currency with the same design except that the Malaysian issue would be designated the "M" series and the Singapore issue the "S" series. The two issues would be legal tender in either country. Each country would control its own issue and the management of its reserves.

In a meeting with his colleagues on July 6, Mr Lee commented that Singapore did not get all the safeguards it had hoped for in the Draft Agreement. He observed that the proposed Agreement was between two unequal parties, for Bank Negara was already an established institution while Singapore had no equivalent central banking machinery. The Prime Minister, however, viewed that the break-up of the Common Currency arrangement would forestall future wider economic co-operation between the two countries. The best option therefore was to accept the Draft Agreement and work towards modifying it over time.

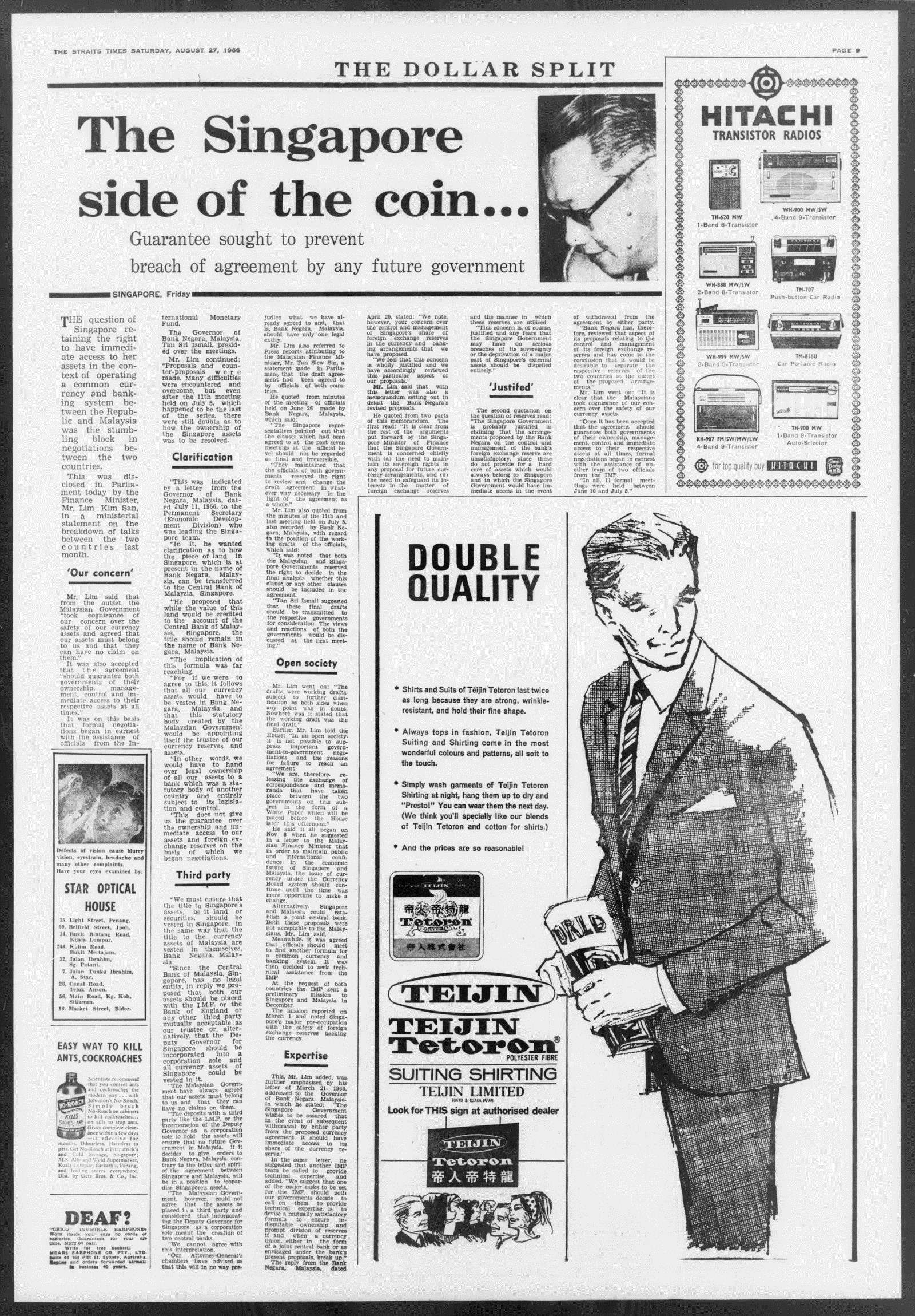

A few days later, that decision was rendered moot. The trigger was a letter dated July 11 from Mr Ismail on the status of a piece of land at Robinson Road in Singapore, the site of the proposed Singapore branch. The Malaysian view was that while the value of the land would be credited to the account of the Singapore branch, the title would remain in the name of Bank Negara Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur's position was that the Singapore branch was not a legal entity and could therefore not own assets.

This was a bombshell. If the Singapore branch could not own property, that would mean it could not be the legal owner of its reserves.

Two days later, Mr Tan wrote to his Singaporean counterpart, noting Singapore's reservations about the Draft Agreement but also adding that a decision was needed by the end of July, as the deadline for placing orders with the London printers for the new currency notes was mid-August. On August 4, Mr Lim flew to Kuala Lumpur to meet Mr Tan at his residence, carrying with him a formal letter of reply.

The letter stated clearly that Singapore would never place its reserves in trust with an agency under the control of a foreign government. It suggested two options. One was to place these reserves with an independent trustee like the IMF or the Bank of England. The other was to incorporate the office of the Deputy Governor overseeing the Singapore branch as a Corporation Sole, and for Singapore's assets to be vested in him and not Bank Negara.

Mr Ismail replied that the Corporation Sole suggestion was unacceptable as it meant a separate legal entity, in effect a separate central bank. In a reply on August 8, Mr Tan also stated that Singapore's proposals were not acceptable. He subsequently visited Singapore on August 13. At a meeting at Rumah Persekutuan, he was given a letter by Mr Lim, which reiterated Singapore's stand that it could not be placed in a position where its reserves might be jeopardised. But Mr Lim expressed a willingness to explore "any alternative proposal" to resolve the impasse.

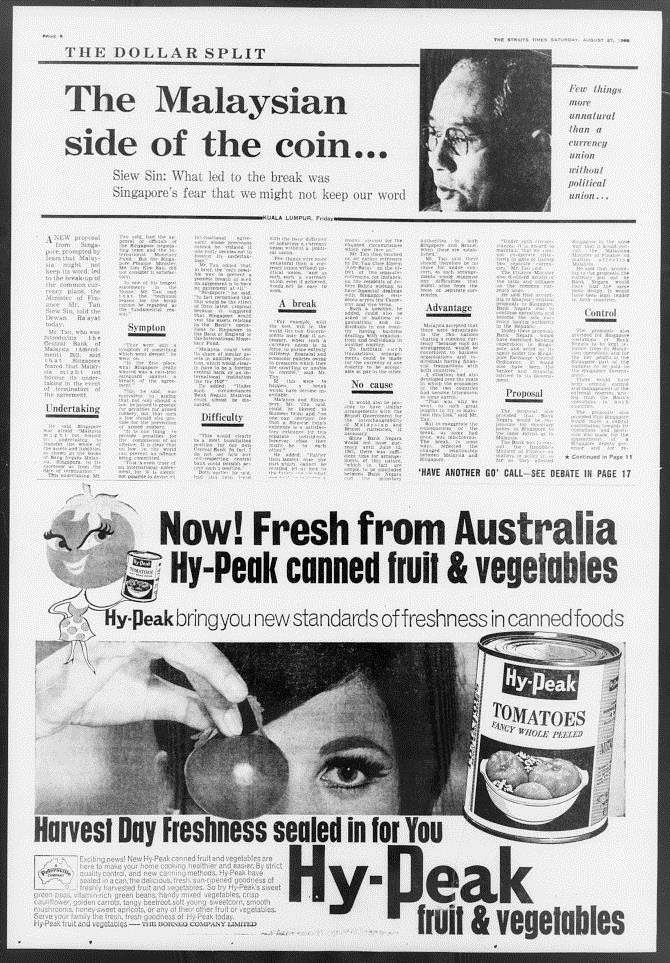

In a reply dated August 17, Mr Tan said the Draft Agreement did ensure that Singapore would have "the whole of the assets and liabilities shown in the books of Bank Negara Malaysia" in the event that the Agreement was terminated. He added: "Your real fear is that we may not honour that Agreement. The only answer to this is clearly to have no agreement at all".

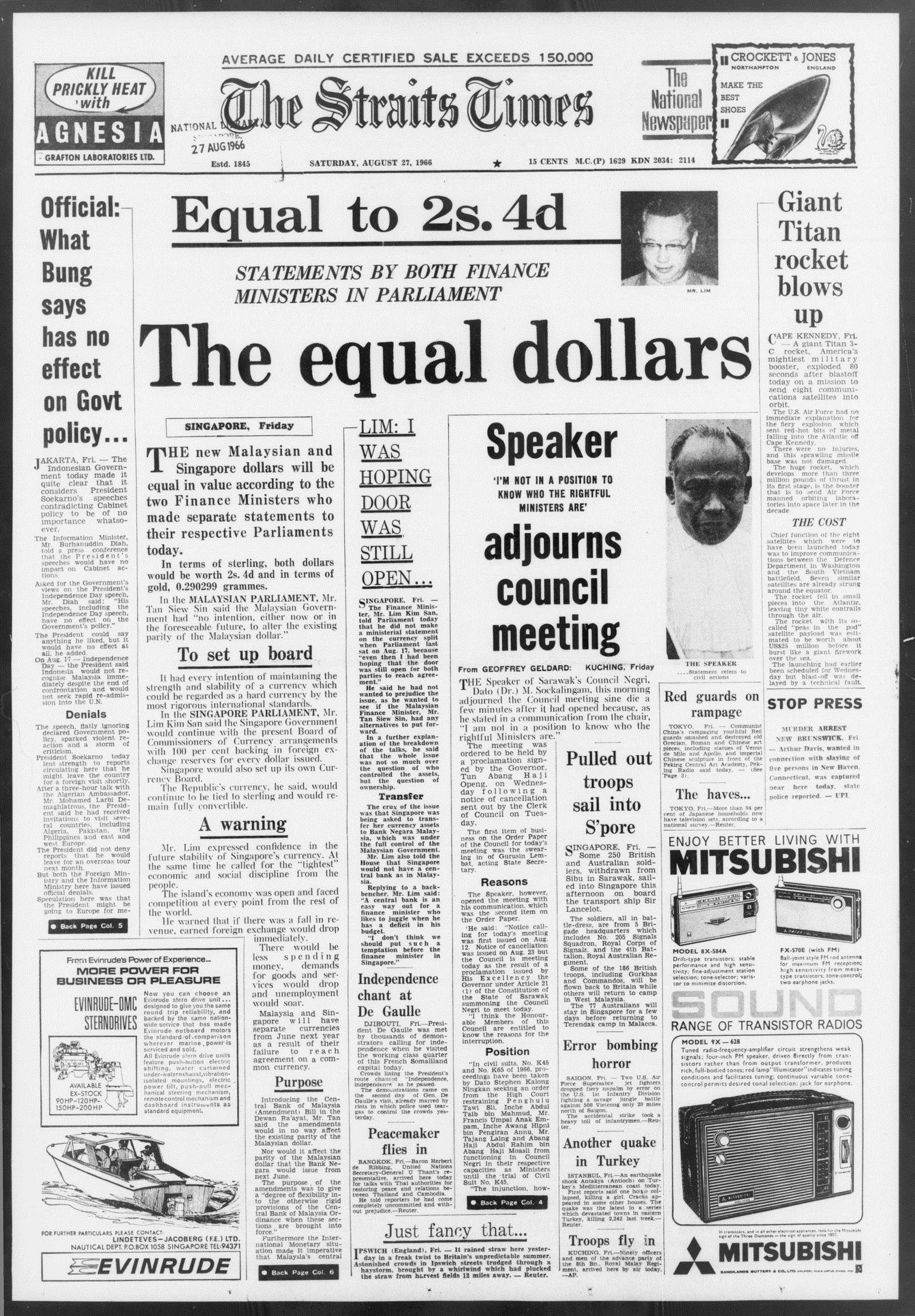

And so it came to pass that at 1.30pm on August 17, 1966, both governments announced to their peoples that Singapore and Malaysia would have separate currencies from June 12, 1967.

Ultimately, the talks failed because Singapore did not receive ironclad guarantees it had indisputable rights over its reserves.

Subsequently, Malaysia and Singapore, together with Brunei, agreed to a Currency Interchangeability Agreement. The agreement allowed for the new Bruneian, Malaysian and Singapore currencies to be used as customary tender, fully interchangeable at par value, in all three countries. The agreement lasted till May 8, 1973.

The first separation had to be followed by a second