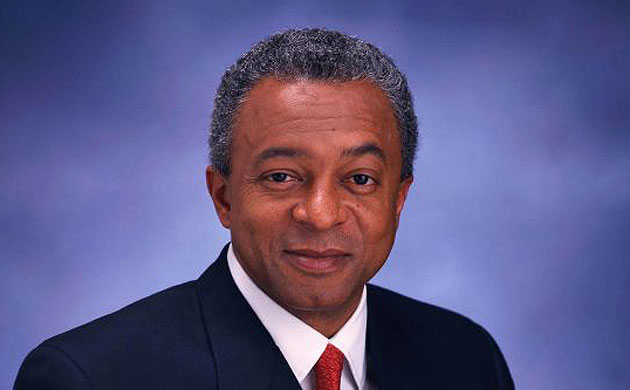

<img src="http://static.guim.co.uk/sys-images/Business/Pix/pictures/2008/03/26/diamond460276.jpg" width="460" height="276" alt="Bob Diamond of Barclays. Photograph: Sarah Lee" />

<p class="caption">Bob Diamond has made £39.8m at Barclays. Photograph: Sarah Lee</p>

</div>

<p>It was Valentine's Day and for <a href="http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2009/jan/24/fred-goodwin-rbs">Sir Fred Goodwin</a> there was a very special present. The youthful banking executive was one of elite group of <a href="http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/royalbankofscotlandgroup">Royal Bank of Scotland</a> directors handed bonus cheques totalling £2.5m as reward for clinching control of the ailing high street lender NatWest.</p><p><a href="http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/jan/24/comment-rbs-bonus-culture">The payments created a furore</a> but Sir George Mathewson, the plain talking RBS executive who had led the eight month campaign, could not understand what the fuss was about. "They wouldn't give you bragging power in a Soho wine bar," an unrepentant Mathewson said. </p><p>The bonuses helped drive RBS along its road to ruin. The bank's executives got the deal-making bug and embarked on an orgy of acquisitions, gobbling up more than 24 companies in the next eight years - culminating in the £50bn <a href="http://www.guardian.co.uk/money/2008/dec/31/investments-city-credit-crunch">record-breaking takeover of ABN Amro</a> just as the <a href="http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/creditcrunch">credit crunch</a> started to bite. </p><p>Nine years on, the bonuses help illustrate what happens when <a href="http://www.guardian.co.uk/money/pay">pay</a> deals reward risk taking and highlight the gulf in pay between boardroom bosses and those who work in the City, earning even bigger bonuses through private pay deals that do not have to be published.</p><p>"Without question my research points to the fact large companies seem to have been paid for getting bigger not better. We saw that with RBS," said Peter Hahn, a fellow in finance at Cass Business School.</p><p>But City pay deals give even boardroom bosses cause for pay packet envy. Mathewson's remarks were aimed at the City where RBS's advisers at investment bank Merrill Lynch - notably corporate financier Matthew Greenburgh - were taking home bigger success bonuses than the RBS board. Greenburgh, who took the lead in many of the Edinburgh-based bank's deals, is rumoured to have shared in a bonus of £10m for his work on NatWest. </p><p>Such eye watering sums of money have been <a href="http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2008/dec/09/bonus-culture-payout-city-firms">paid out in City bonuses</a> for two decades but the City minister Lord Myners - who sat on the board of NatWest at the time of the RBS takeover - has proclaimed the "golden days of huge bonuses in the investment banking arms are gone".</p><p>"I have met more masters of the universe than I would like to, people who were grossly over-rewarded and did not recognise that. Some of that is pretty unpalatable," Myners said last week.</p><p><a href="http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2008/oct/17/marketturmoil-creditcrunch">Adair Turner, the chairman of Financial Services Authority</a>, has gone further still, suggesting the vast rewards on offer sucked talent from more productive parts of the economy. "In the years running up to 2007, too much of the developed world's intellectual talent was devoted to ever more complex financial innovations, whose maximum possible benefit was at best marginal, and which in their complexity and opacity created large financial stability risks," he said.</p><p>The concern about City bonuses has not just been their size but the way they are structured. In existence for long before the credit crunch, they were once regarded as a legitimate way to pay staff in an industry that has cyclical earnings and only one real cost: people.</p><p>Richard Lambert, director general of the CBI, said: "Before all this happened you would say bonuses were the right way to reward people where the highest costs are salaries and revenues are very volatile." </p><p>In the old-style City partnerships the profits were distributed among partners at the end of each year. They were largely profits generated from giving advice to companies and did not involve taking big risks that could backfire later.</p><p>But when US investment banks started to operate in the City 20 years ago they took bonuses to new dimensions: the major US players used their balance sheets to bolster profits by allowing traders to use the banks' own money to take bets on the financial markets. Bonuses were bigger because profits were bigger. And rival banks were paying even bigger sums which drove up bonuses in a never ending spiral.</p><p>As the credit boom exploded it became apparent that banks had encouraged their traders to devise complex financial products that fuelled profits and in return added zeros to their bonuses. Those complex instruments - usually characterised by acronyms such as CDOs or CDSs - are now among the toxic waste clogging up the financial system and being ring-fenced by governments desperate to revive their collapsing economies.</p><p>Trades that looked hugely profitable little more than a year ago, are now loss making. But the bonuses have already been paid and pocketed by traders, with shareholders, and in many cases the taxpayer, left to shoulder the pain.</p><p>The financial crisis has forced the City to come to terms with the excesses of the bonus culture. Hahn recalls that in his days as banker, new entrants to a firm were aspiring to a lengthy career that might, if they were lucky, culminate in them being the chief executive. Not any more, he said.</p><p>"People felt they were entitled to a bonus. The bonus was everything. It's hard to describe the pressure because the amount is enough to pay off your mortgage," he said.</p><p>One City worker believes there is now a "gradual realisation that the glory days are gone". He explains that MBA students were lured to the industry despite its 60 hour weeks and gruelling weekends at their desks because of the promise of bonuses. </p><p>"Young people came into the City and gave up their lives but knew they would become filthy rich at the end of it. Not any more. Most people have lost their entire net worth," he said.</p><p>Herein lies the problem at the heart of the debate about rethinking City culture. Big banks all paid some part of their bonuses in shares - the one thing that pay experts have always argued should keep a cap on excessive risk taking because it is in everyone interests not to damage a share price.</p><p>It has been proved not to be true - no more so than at Lehman Brothers and <a href="http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/bearstearns">Bear Stearns</a>, the two US investment banks that collapsed year, wiping out their share prices and in the case of Lehman paralysing the financial system. Both banks were lauded for their employee share ownership culture</p><p>Hence the attempts to devise new ways to pay bankers - and crucially be able to claw back bonuses paid for performance that proves to be short-lived. <a href="http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/goldmansachs">Goldman Sachs</a>, regularly nicknamed Goldmine Sachs for its extraordinary rewards, has always been able to demand traders hand back shares awarded for previous performance.</p><p>Swiss bank <a href="http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/ubs">UBS</a>, the biggest continental European casualty of the credit crunch, has devised a novel "bonus-malus" system under which bonuses for the top executives are held back to discourage risk taking. The bank intends to introduce the system in the boardroom first and then for key managers in risky parts of the businesses. But UBS executives acknowledge privately that implementing the system lower down could prove more difficult.</p><p>Hahn argues that getting pay right at the top is the crucial thing. "If you're the chief executive and the head trader comes to you and says we made an extra billion bucks because we took a big bet ... you're not going to pay him for it (if your own bonus doesn't pay out)".</p><p>One senior banker reckons the best way to keep excess in check would be to devise a greed detector test for fresh entrants. The government has charged the Financial Services Authority with sorting out the problem. The regulator has visited the biggest firms in the City and scrutinised bonus structures not just for top executives but throughout the organisations. The FSA has warned that those firms with pay structures that encourage too much risk taking could be forced to set aside more capital.</p><p>It is not yet clear how the system will be enforced but Lambert said this is one way that the lid could be kept on pay. "Regulators will require financial firms to take less risk and require them to hold more capital. Profits won't be as high and the capacity to have huge compensation will be less," he said.</p><p>Academics writing in the National Bureau of Economic Research also argue that the higher wages in the financial industry will eventually disappear. "Wages in finance were excessively high around 1930 and from the mid 1990s until 2006," Thomas Philippon of New York University and Ariell Reshef of the University of Virginia said. </p><p>Even after a year such as the last, when taxpayers around the world have bailed out their banks, bonuses have still been paid. UBS is the latest, preparing to pay out bonuses from a bonus pool reported to be SFr2bn (£1.24bn). Regulators are said to have forced a SFR1bn reduction in the size of the total payouts. Bonuses, though, nonetheless.</p>

</div>