The dollar is dead, long live the dollar

April 05, 2023

Ian Bremmer

Jess Frampton

Every now and then, a story about some country seeking to diversify away from the US dollar kicks off a frenzy about the inevitable collapse of dollar dominance. Lately, there’s been

more than a few such headlines, including:

Naturally, these have provided a fertile ground for

gold bugs,

crypto shills,

hyperinflation truthers,

techno-libertarians,

anti-imperialists (read: anti-US zealots), and run-of-the-mill grifters to stoke fear about the dollar’s imminent death and its supposedly catastrophic consequences for the United States and the global economy.

But even

mainstream media outlets and

smart, well-meaning analysts have gotten swept into the current wave of hysteria.

Doomsayers offer numerous reasons for the dollar’s demise. They point to everything from China’s meteoric rise to superpower and the emerging multipolarity of the global system, to America’s stagnant productivity growth, chronic fiscal deficits, monetary expansion, growing debt burden, trade wars, financial fragility, and imperial overreach, to challenges from disruptive technologies like central bank digital currencies and crypto-assets.

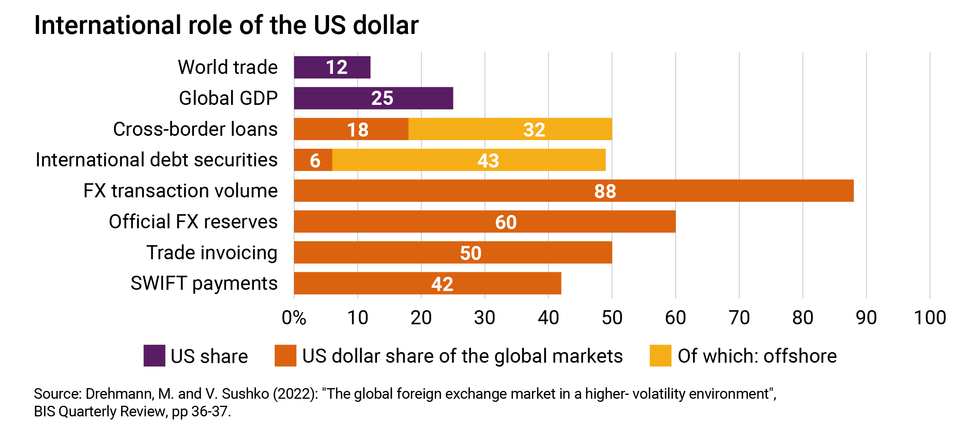

Yet rumors of the dollar’s death are greatly exaggerated. Going by most usage

measures, the dollar remains incontrovertibly dominant in global trade and finance, if a little less so than at its apex.

Whereas most currencies are only used domestically or in cross-border transactions that directly involve the currency’s issuer, the dollar continues to be widely used for funding, pricing, trade invoicing and settlement, and cross-border borrowing and lending

even when the US is not involved.

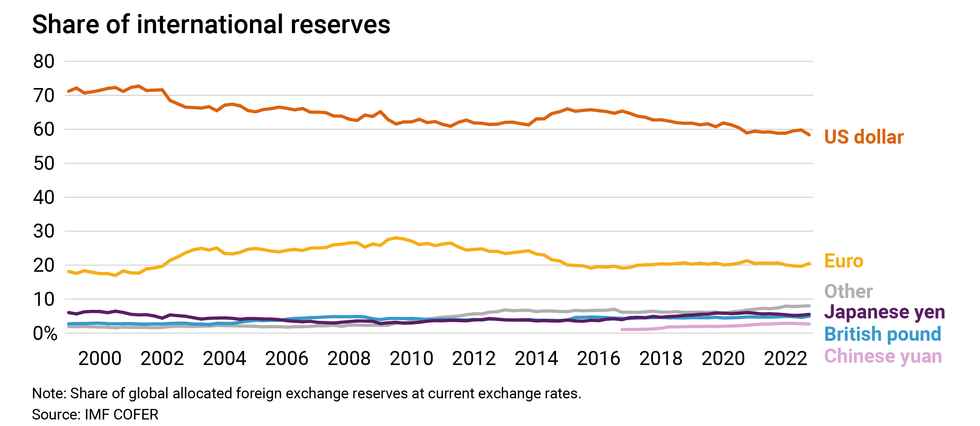

While the dollar’s share of the central banks’ $12 trillion foreign exchange reserves has indeed declined since 1999, it is still

nearly twice that of the euro, yen, pound, and yuan

combined – the same as it was a decade ago. Its nearest competitor for global currency status, the euro,

accounts for barely 20% of central bank reserves compared to the dollar’s 58%, followed by the Japanese yen at 5%. The much-touted Chinese yuan lags far behind at under 3% of foreign exchange reserves.

Even China, in an environment of intensifying geopolitical competition with the US and having just witnessed Washington’s weaponization of the dollar against Russia, has had no choice but to continue

accumulating dollar-denominated assets.

Why has dollar dominance remained so sticky? In large part, it’s because incumbency is self-reinforcing. People use dollars because other people use dollars; dollar dominance begets continued dollar dominance.

But it’s not just turtles all the way down. The dollar has inherently desirable features: It is at once highly stable, liquid, safe, and convertible. And US financial markets are by far the largest, deepest, and most liquid in the world, offering an abundance of attractive dollar-denominated assets foreign investors can trade. No other market comes remotely close. As we saw during the recent banking panic, every time turmoil roils global markets, the dollar strengthens as investors flock to the most plentiful and liquid safe assets in existence. In fact, the dollar emerged from the crisis

nearly as strong as it’s been in 20 years relative to other major currencies.

Ultimately, investors want to hold dollar assets because America’s economic, political, and institutional fundamentals inspire credibility and confidence. The US has the world’s strongest military, the best research universities, the most dynamic and innovative private sector, a general openness to trade and capital flows, relatively stable governing institutions, an independent central bank, sound macroeconomic policies, strong property rights, and a robust rule of law. People all over the world trust the US government to safeguard the value of their assets and honor their rights over them, making the dollar the ultimate safe-haven currency and US government bonds the world’s most valued safe assets.

None of this means that the dollar’s advantage can’t slip, of course. After all, every reserve currency that came before the dollar was dominant until the very moment it ceased to be.

For much of the 19th century, the global currency of choice was the British pound, owing to the British Empire’s vast territorial reach, economic supremacy, and advanced banking and legal system. It was only definitively displaced by the US dollar once the US had become an economic superpower. Following World War II, US GDP accounted for roughly half of the world total, so it made sense for the dollar to be the global means of exchange, unit of accounting, and store of value.

America’s economic supremacy has since waned, its share of global output now a fraction of what it was in 1945. This trend has led many to worry that the dollar will soon follow in sterling’s footsteps. But there’s a big difference between now and then: When the pound lost its status, there was another currency on the sidelines ready to take its place. Today, there is no such challenger.

Of the putatively serious candidates to dethrone “King Dollar,” the euro is not a viable alternative because of Europe’s persistent fragmentation. Despite having a sizeable economy, well-developed financial markets, decently free trade and capital openness, and generally robust institutions, Europe lacks true capital markets, banking, fiscal, and political union.

Ever since the 2009 eurozone crisis, European bond markets have been much more fragmented and shallower than America’s, leaving investors with a dearth of high-quality euro-denominated assets. While the pandemic did push the EU to finally issue common debt to fund recovery efforts, that move alone was not sufficient to boost the euro’s international role, as markets know that even if full fiscal and financial integration was on the horizon – a big if – political integration isn’t.

The Chinese yuan, meanwhile, is not a viable alternative because of Beijing’s authoritarian and statist bent. In fact, Xi Jinping’s policy preferences – economic self-reliance, financial stability, common prosperity, and political control of the economy – run directly counter to his global-currency ambitions.

Despite its growing role in the global economy and long-standing

desire to unseat the dollar, China lacks the investor protections, institutional quality, and capital market openness required to internationalize a yuan that is still not fully convertible overseas. Persistent currency and capital controls, an opaque banking system with too many non-performing loans, spotty contract enforcement, and often arbitrary and draconian regulations will all continue to undermine Beijing’s efforts to elevate the yuan.

Last and most definitely least, so-called cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are not a viable alternative because they are speculative assets with no intrinsic or legislated value. By contrast, as legal tender, the US dollar is backed by America’s current and future wealth – and by the US government’s ability to tax it.

I say “so-called” cryptocurrencies because these digital tulips are not really currencies or money: they are very

expensive and

slow to transact in, they can rarely be used to pay taxes or buy groceries, and they are far too

volatile to be useful as means of payment, stores of value, or units of account. Nor are they

truly decentralized, as the

FTX meltdown proved.

To be clear, it’s not completely accepted that losing reserve currency status would be a bad thing for the United States. In the 1960s, France’s then-finance minister Valéry Giscard d’Estaing famously claimed that being the issuer of the global reserve currency afforded America an “exorbitant privilege,” allowing it to borrow cheaply from the rest of the world and live beyond its means.

But there’s a

downside (or “exorbitant burden”) to USD reserve status: Foreigners’ insatiable appetite for dollar assets pushes up the dollar’s value, making American exports artificially expensive, harming American manufacturers, increasing American unemployment, suppressing American wages, forcing America to run chronic deficits, and widening American inequality. One could argue that the US should welcome – and, indeed, work toward – a smaller role for the dollar, and that contenders like China and Europe should be loath to replace it.

The most serious threat to dollar dominance might come not from abroad (Europe, China) or from beyond (cyberspace) but from within. The United States is still the most powerful nation on earth, but it’s also the most politically divided and dysfunctional of all the major industrial democracies. The single biggest risk to the dollar’s global status is that growing inequality, tribalism, polarization, and gridlock eventually undermine trust in America’s stability and credibility.

At the end of the day, though, no matter how much the dollar seems to lose its shine, global currency status is about relative – not absolute – advantages.

Without a viable challenger, it’s very unlikely that the dollar will lose its special role anytime soon – for better or worse. You can’t replace something with nothing.