Tale of two Guangdong cities: the reinvention of Shenzhen

Part one of two: Twin powerhouses of southern China face starkly different futures: both were major manufacturing engines but one has shifted gear into the new economy while the other is left spinning its wheels.

PUBLISHED : Monday, 01 February, 2016, 11:59pm

UPDATED : Monday, 01 February, 2016, 11:59pm

He Huifeng and Nectar Gan

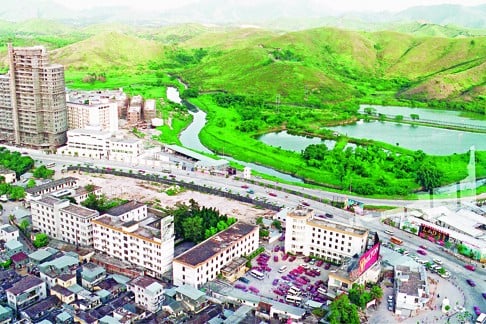

Shenzhen has gone from a rural village to a factory centre and is now entering the new economy age. Photo: SCMP Pictures

Hong Kong businessman Peter Chai Kwong-wah faced a tough choice: after 20 years of running a toy factory in Shenzhen, profits were locked in a downward spiral. At age 66, Chai could close up shop and retire or he could try to re-energise the business by relocating to another Asian country where the overheads were lower. He gave it another go and moved operations to Vietnam.

At around the same time, in another part of the city, Frenchman Homeric de Sarthe made a similar life-changing choice. After living in China for several years, the 27-year-old decided the time was right to launch his social media app, Shosha.

Chai and Sarthe represent the broader transformation that Shenzhen is undergoing, shifting from a manufacturing powerhouse to a global technology hub. Its success in managing the transition is owed partly to forward-thinking policies, observers say. But it’s also due to its residents, many of whom originate from elsewhere and are comfortable taking risks, accepting failure and trying again.

These traits have helped Shenzhen to weather the economic headwinds better than most mainland cities. As Beijing limped along on 6.9 per cent growth in the first nine months, Shenzhen managed 8.9 per cent.

That expansion was partly on the back of six emerging industries – biotechnology, the internet, new energy, new materials, information technology, and cultural and creative industries, which together grew 17 per cent last year.

These sectors constitute a big slice of the city’s economy – contributing more than 40 per cent of its gross domestic product growth last year. And the share is rising, coming in at 39.6 per cent in the first three quarters.

The hope is that it will keep doing so. Mayor Xu Qin said early this year the authorities would continue to encourage labour-intensive manufacturing to relocate while drawing in internet and tech-driven industries.

Shenzhen in 1993, just a few years into its economic transformation from a rural village into a manufacturing centre. Photo: SCMP Pictures

The changes are expected to create a city that bears little resemblance to the Shenzhen of past decades. When Chai arrived in 1993 labour and raw materials were cheap, and officials encouraged Hong Kong companies to set up factories.

Chai established Milliard Toys Manufacturer and became a multimillionaire churning out Hello Kitty products for Japan and Disney items for the United States and Europe. At its peak, the company employed 10,000 workers. But profits from toy manufacturing began to fall around 2007. Only a few dozen workers were needed to keep production going.

Peter Chai Kwong-wah has relocated his toy firm to Vietnam, where costs are lower. Photo: SCMP Pictures

Chai thought about shutting the venture and retiring, but decided to relocate to Hanoi, where he now has about 4,000 people working for about half what he would pay employees in Guangdong. His company is part of the exodus of low-value manufacturers leaving the city as it seeks to re-invent itself as the next Silicon Valley.

Beginning in 2013, Shenzhen has funnelled more than 4 per cent of its GDP into research and development every year, putting it on par with South Korea and Israel. The city now accounts for almost half of the mainland’s international patent filings – about 13,300 last year.

The city is the world’s largest manufacturer of electronics, home to Apple supplier Foxconn and other key tech players such as internet giant Tencent and telecoms like Huawei and ZTE.

It also has a vibrant grass-roots manufacturing ecosystem with tens of thousands of smaller factories, design houses, and product integrators.

The city’s economy is agile because the government is less involved, according to Qu Jian, deputy director of the Shenzhen-based think tank China Development Institute.

“Shenzhen is one of the few cities in China relying on the force of the market to develop its economy. Apart from land allocations, the government rarely intervenes in commercial operations,” Qu said.

“This is crucial for company innovation. Heavy-handed governments make it hard to push for technological innovation. Scientists, technicians and company owners have to be able to shoulder risks and explore. Government interference is very inefficient.”

Qu said most companies in Shenzhen were either privately owned or foreign-funded – types that were more willing to take risks and use innovation to maximise value. “The internal mechanics of state-owned enterprises mean they are slow actors in technological innovation and industrial restructuring. They don’t dare take risks because the SOE chiefs have to shoulder the responsibility for them. That’s why they’re conservative and prefer industry monopolies,” he said.

Another of Shenzhen’s assets, found also in Silicon Valley, is that a large part of the population hails from somewhere else. They are more willing to risk failure and try new ideas, according to Qu. “Shenzhen is a typical immigrant city with a tolerant society. Most of its residents are not from here, but everyone calls themselves a Shenzhener.”

It’s that environment that attracts young people to begin tech ventures, like drone maker DJI, founded by 35-year-old Wang Tao in 2006. DJI controls about 70 per cent of the global market for civilian drones and ranks as one of the country’s most valuable start-ups, worth an estimated US$10 billion.

Wang Tao founded drone-maker DJI in Shenzhen. It’s now worth an estimated US$10 billion. Photo: Xinhua

Others have followed in Wang’s footsteps. Last year, Gu Ying, Leo Fuji Zhang and Zhang Shinan, all in their mid-20s, set up TT-Kuaiche, an app that directs drivers to nearby carwashes. It has swiftly expanded across the mainland and entered its second round of financing last month, attracting US$30 million from online media company Sina and Sequoia Capital China, an arm of the California-based venture capital firm.

“Only in Shenzhen do start-ups such as ours have access to great funding and government support,” Gu said.

They are joined by a small but growing number of foreigners who choose Shenzhen as the launchpad for their new economy ventures. Sarthe and two friends introduced Shosha – or Shoot and Share Your Life – in September after several years of absorbing the city’s personality.

“To me, Shenzhen is still developing and new. Our app idea was actually inspired by our experience of living in this city, where a growing number of foreign people are coming for business opportunities and living apart from their family,” Sarthe said.

“We have friends and a network” in Shenzhen, says Homeric de Sarthe, who launched the social media app Shosha. Photo: SCMP Pictures

The mainland market with its big population is perfect for an app like ours. We enjoy being in Shenzhen because we have friends and a network. The number of start-ups is constantly increasing, making it a great environment to share ideas and have people help one another. The infrastructure is well established and more incubators are being created.”

But not everybody is convinced the immediate future will be so bright. Arnold Lou, a telecommunications engineer who runs a tech company in the city, said he city could be severely impacted by the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a US-backed Pacific Rim trade agreement that excludes China.

“I think it needs more attention, especially as Shenzhen’s reputation and success are based on its hardware manufacturing,” Lou said.

“I can’t help but think about what will happen once the TPP is up and running. The authorities are trying to downplay it but you see more electronic manufacturers, especially those from Taiwan, Hong Kong and overseas, moving to TPP-backed countries, like Vietnam, Taiwan, India and even Japan.

“I still think manufacturing and international trade are fundamental to the city. Shenzhen should at least prepare for possible fiercer competition.”

Qu agreed that a global perspective was crucial if Shenzhen was to succeed. It had made its first giant leap from a small village to a special economic zone. Now it had entered its second phase of identity to become China’s economic centre in the south.

“The top priority for Shenzhen in the next five years is to become an international city. Its government should learn from Singapore and adopt an international way of thinking to plan for the city’s development and manage its economy,” Qu said.

“Local businesses should venture overseas. There are successful examples like Huawei and ZTE, and we need more.”